Tired of modern? Can’t afford original? Grab a vintage revolver that isn’t and hold on for the ride!

by Wayne van Zwoll

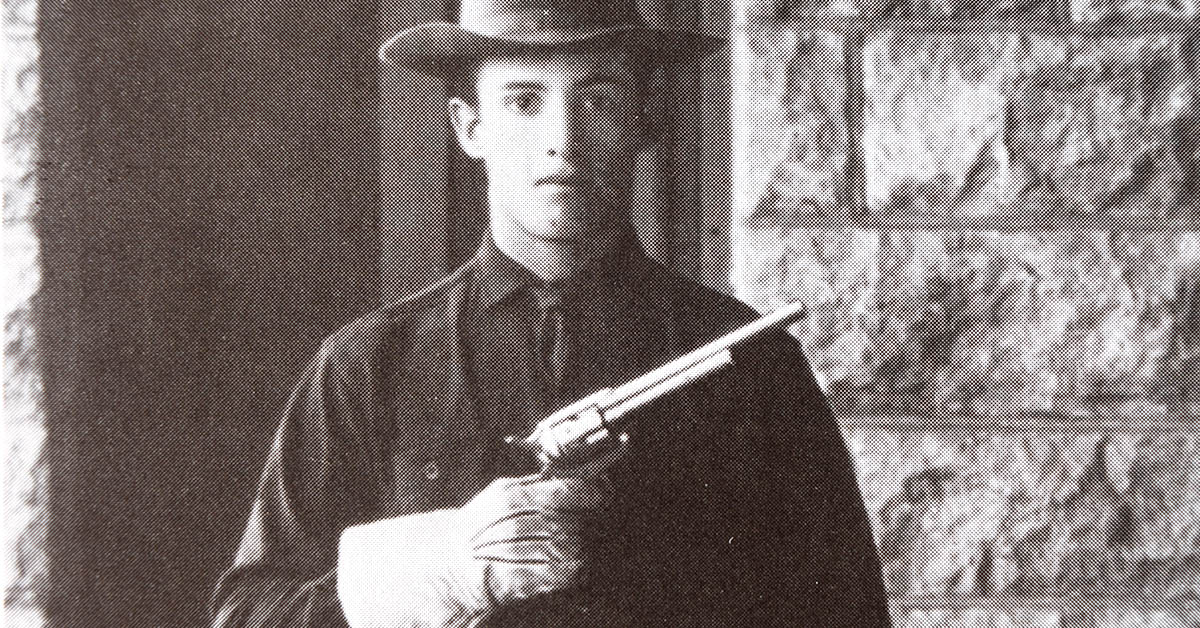

“I had always loved the old single-action Colt. I can remember yearning for one when I was just fourteen [and] living in New York City….” William Batterman Ruger would so-explain his introduction of the Single Six .22 revolver in 1953, and of its centerfire kin, the Blackhawk, two years later.

“Rebirth of the single action,” proclaimed Shooter’s Bible. Actually, it was a new revolver that borrowed from the profile of Colt’s Single Action Army. The Ruger boasted an adjustable sight and “best quality music wire springs throughout, no leaf springs.” Price: $87.50

If that first Blackhawk now seems a bargain, well, it was. If you own a first-generation Colt SAA, consider yourself truly blessed. At its debut, the black-powder Model of 1873 sold for $17.50. An original specimen with modest wear might today fetch $90,000, says my dog-eared Blue Book of Gun Values.

The other day at the range, I slipped a plow-handled six-gun from its holster, thumbed its hammer to a crisp half-cock, and flipped the loading gate open. My favorite .45 loads are much like those that kept the frontier lively. Their fat brass hulls and gray lead pates add gravitas to any gun-belt. Thick, 250-grain missiles shuffling away at 855 fps upended many an hombre who’d have endured lighter blows.

Billy the Kid, felled in his room by Pat Garrett’s .45 one New Mexico night, had used an SAA. So had Emmett Dalton, sole surviving member of the five-man Dalton gang after its 1892 attempt to rob two banks in Coffeyville, Kansas. Cole Younger of the James-Younger gang favored an 1873 Colt; Jesse James died at the muzzle of Robert Ford’s. Remorseless Harvey Logan carried his Colt as Kid Curry with Butch Cassidy’s Wild Bunch and added names to chain killings before turning the muzzle on himself. He shot lawman George Scarborough dead four years after Scarborough fired seven bullets into John Selman, also sworn to the badge. Selman’s .45 had perforated Texas gunslinger John Wesley Hardin after Hardin threatened his son. The line between justice and revenge could be thin indeed!

The appeal of Colt’s 1873 owes much to history. Then there’s the feel. It’s not of the automobile age, but of an era when lads behind horses cut virgin sod in the wake of migrating bison. Samuel Colt copied the plow’s handle for his 1851 Navy and 1860 Army revolvers, then for the SAA. The “thunk” of a cartridge dropping home, the spindle-smooth whirl of the indexing cylinder, the snap of the gate, the long, rocking sweep of the hammer, its castanet clicks keeping time with your thumb over a flat spring….

Well, you get the idea. But I can’t afford an original Colt. The other day, my .45 was a Traditions 1873—a modern version with a transfer bar replacing the Colt’s nippled hammer for safe six-round carry. It was built by Pietta, one of a handful of Italian firms that specialize in reproducing firearms of our early West. Mine, with a 5 ½-inch barrel, is of Traditions’ upscale Frontier line—barrel and cylinder bright blue, the frame case-colored. It lists for $569 (as do 4 ¾- and 7 ½-inch versions, and .357 Magnums with 3 ½-, 4 ¾-, and 5 ½-inch barrels). In .44 Magnum, it’s $609. Nickel finish, machine-cut engraving, and imitation ivory grips command a modest premium.

Boom! The revolver rocks easily. So it was designed. You don’t grip an SAA but let it pivot, nose up, in the smoke. Magically, gently, it settles on point, your thumb licking the hammer on the way down. Snickickety. Boom! Thank uncanny balance, perfect placing and proportions of trigger, hammer, and that plow-handle grip.

Accuracy? It was one of those days. From habit, I loaded only five chambers. Every five shots I’d pull or twitch one out of the group. The Traditions 1873 sent three into an inch at 25 yards; the best four-of-five series averaged 2 ½ inches (four groups) with Black Hills Cowboy loads. Modest recoil and silky function. The feel of a Colt at a small fraction of the price!

While the SAA sold briskly after its 1892 retirement from the Army, demand slipped during the Depression. DA revolvers and auto pistols dominated a recovering economy at the end of WW II. In 1946, Shooter’s Bible listed SAAs at $38.50. Colt resumed production a decade later, hiking the price to $125.

Bill Ruger wasn’t alone, spotting opportunity in nostalgia. The 1950s ushered in Colt clones from Great Western. “Every part … in the Great Western Frontier is interchangeable with the original Single Action Army [save] hammer and trigger and bolt screws, [changed] to prevent the ‘shooting loose’ habit ….” Priced at $97.50 (.38 and .45) and $125 (.44 Special and .357 Atomic), Great Westerns had floating, frame-mounted firing pins and withstood proof loads to 52,000 psi.

A century after the SAA’s 1878 debut in .44-40, black powder enthusiast Mike Harvey and wife Mary Lou opened a gun-shop in Houston. After Mike built a muzzle-loader from scratch, he bought Allen Firearms. Cartridge rifles and revolvers followed front-loaders. Then Mike visited Brescia, in Italy’s “gun valley.” He engaged Uberti to replicate in modern steel Colt’s SAA: “every detail except proof marks.”

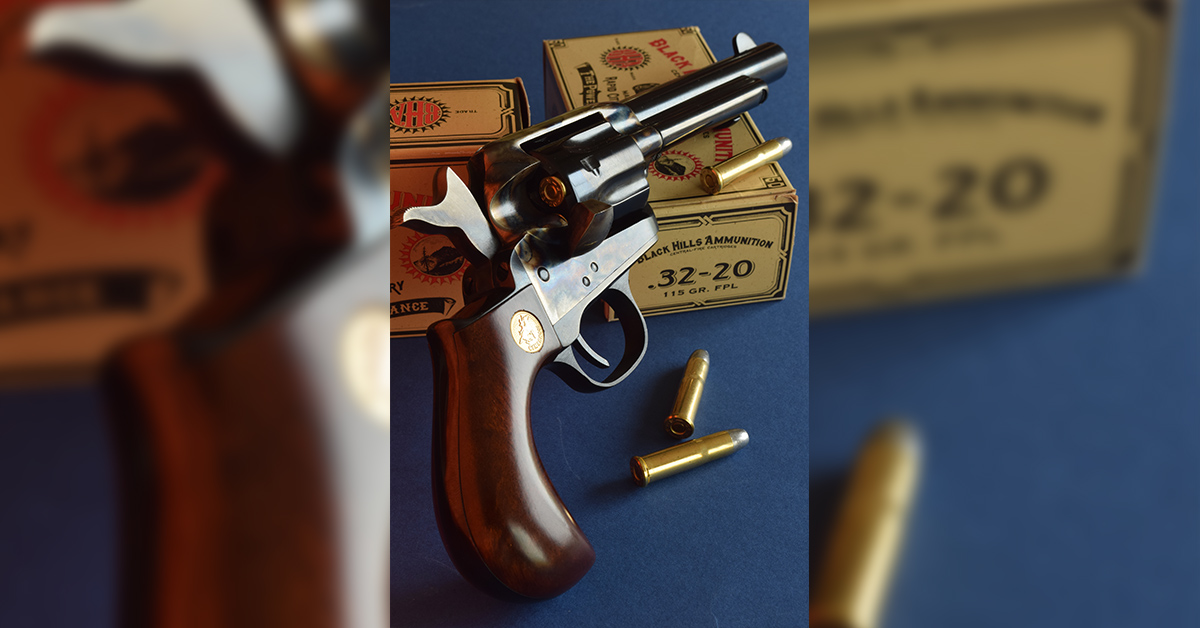

So began Cimarron Firearms. Harvey has since worked with Uberti and other quality-conscious Italian gun-makers to reproduce more historically important firearms. Most date from the 1860s and ’70s. But like Traditions, Cimarron lists cap-and-ball revolvers, too. From Colt’s Walker and Baby Dragoon to the 1851 Navy favored by Wild Bill Hickok, you get Old West style and handling, reliable mechanisms and steels that take frisky smokeless loads. Besides the 1873, you’ll find Lightning and Thunderer DAs in finishes from antique to bright charcoal blue. Not all are .44s and .45s. I snared a .32-20 with bird’s head grips to share the fun with my wife Alice. “It’s cute!” she squealed, then, after one cylinder: “It’s mine!”

No lust for a Colt? Look for reproductions of 1858 Remingtons, and Richards-Mason conversions that adapted percussion handguns to cartridges, and the Smith & Wesson Model No. 3 Schofield hinged-frame revolver that in speed trials, loading and unloading from horseback, trounced the SAA.

Italian gun-makers have proven adept at building film-famous firearms, too. Think: a Wyatt Earp Buntline, a Doc Holliday Thunderer, a Wild Bunch 1911 from Sam Peckinpah’s 1969 western.

Other importers, including Dixie Gun Works and Taylor’s & Company, compete with Cimarron and Traditions in the revolver arena. Cowboy Action events benefit all. In 1993, Ruger joined the scrum with its Vaquero, true to the SAA in profile, but with mechanical innovations. At $394, this six-gun was irresistible. I bought one.

Old West revolvers enchant people who’ll never grab the handles of a plow. They evoke images—many sanitized by time—of frontier’s promise, of manifest destiny. They bring to mind the brief era of cattle trails, bison hunts, the Pony Express, and Indian wars on the Plains, the reckless lives of a generation scarred by civil war.

Reproduction firearms deliver those images at bargain prices—with the singular marriage of form and function that marked revolvers of that era.

The Original

Colt’s 1873 Single Action Army was among the earliest revolvers to fire metallic cartridges. The .45 Long Colt was also a powerful round. First loaded with 28 grains of black powder behind a 230-grain bullet, it earned a deadlier 40-grain charge pushing a 255-grain bullet. The Army adopted the revolver in 1875 and would keep it 17 years. Peacemaker was a common nickname, possibly from B. Kittredge & Co. of Cincinnati, a Colt agent. Six-shooter, hogleg, and other monikers followed. In 1878, Colt bored its SAA for Winchester’s .44-40 (.44 W.C.F.) cartridge, available in that company’s 1873 rifle. Packing one load for handgun and rifle made sense on the frontier. No mix-ups. And both firearms were in service down to the last shot. In 1896, the vertical screw securing the Colt’s cylinder pin gave way to a horizontal lock. The “smokeless frame” was born….

What’s the chance…?

A Double Eagle gold piece minted in 1873 contained .9675 ounce of gold. Most places, it would have bought a new Colt SAA, a holster, and a box of cartridges. Now at about $1,300 an ounce, gold has appreciated less than the revolver. Even a current single-action Colt from the Custom Shop, with no age or history to add value, brings $1,800. So, if you found an early Peacemaker in an old house, as did one fellow in 1925, you’d surely have paid the $4 he gave the widow of the Army officer who had owned it. This SAA, it turned out, had likely never traveled far from its New Hampshire home. It had no recorded link to frontier bloodshed or prominent people. Still, at a Christie’s auction in 1987, it fetched $242,000.

Which is why, after parting with a much later SAA, I was referred to a psychiatrist.