Ivory drew men with muzzleloaders, as had bison. Elephants proved the more difficult quarry.

by Wayne van Zwoll

In 1873, Winchester announced its first centerfire cartridge, the .44 W.C.F. (.44-40) and a lever-action repeating rifle to fire it. The U.S. Army issued its first .45-70 rifles. And Samuel Colt trotted out his Single Action Army revolver.

In Africa, explorer and missionary David Livingstone died at 32.

Hunters were already killing buffalo for market on our western frontier, and elephants for their ivory in Africa. Elephants would outlast buffalo. Claimed by a suite of European empires, sub-Saharan Africa dwarfed the Louisiana Purchase. Tuskers took refuge in trackless forest and bush.

The Buffalo Hunters

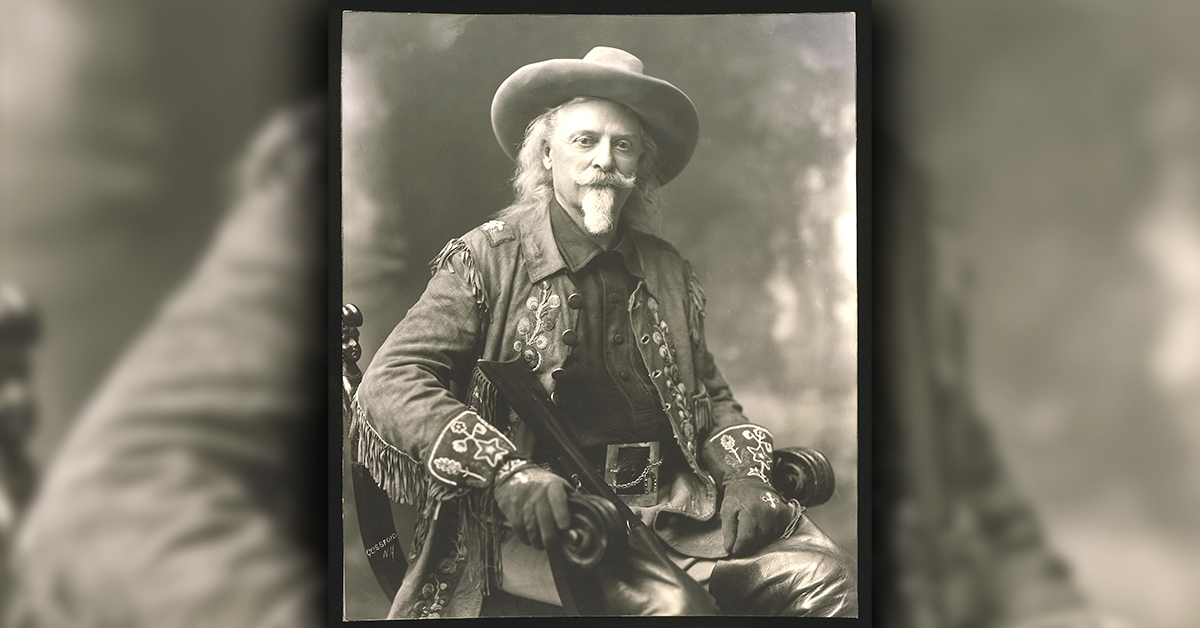

By the late 1880s, American bison had been shot to tatters. Remnant bands roamed prairie littered with three million tons of bones. William F. Cody was perhaps best known of the hunters who, beginning in the late 1860s, laid the great herds low. Born in Iowa Territory in 1846, Cody lived an abbreviated youth. By 14 he was riding as a message boy for Russell, Majors, and Waddell, who started the short-lived Pony Express. Early in the Civil War, he served as a Union scout, enlisting with the 7th Kansas Cavalry in 1863 to fight in Missouri and Tennessee. After Appomattox, he served at Fort Ellsworth, Kansas, as a civilian scout. There he began hunting for the Army and the Union Pacific. By his count, he shot 4,280 buffalo in 18 months during 1867 and ’68.

Cody’s efficiency inspired this ditty, reportedly from rail crews:

Buffalo Bill, Buffalo Bill.

Never missed and never will.

Always aims and shoots to kill.

And the company pays his buffalo bill!

Evidently the title pleased Cody.

But other hunters also claimed the moniker. One was Billy Comstock, born in Comstock, Michigan, in 1842. His career path paralleled Cody’s. Riding for the Pony Express in the West, he became a civilian scout for the Army and a hunter for the railroads. Comstock’s shooting impressed officers at Fort Wallace, Kansas. In 1868, he and Cody agreed to a buffalo-killing contest, sponsored by the Kansas-Pacific Railroad, east of Fort Sheridan.

“We were to hunt one day of eight hours,” Cody later recalled, “[with] five hundred dollars a side [paid to] the man who should kill the greater number of buffaloes…” He claimed the edge, as his mount Brigham was “the best buffalo horse that ever made a track,” and he had a better rifle, “known at the time as the needle-gun, a breech-loading Springfield. Comstock was armed with a Henry [and] could fire a few shots quicker, [but] it did not carry powder and lead enough to do execution equal to my caliber .50.”

That .50 was the .50-70, the U.S. Army’s first centerfire cartridge. Cody had acquired his “needle gun,” named for its long firing pin, in 1867 and used it for most of his hunting. Manufactured as an 1866 muzzleloader, it was fitted with a “trap door” breech developed by Springfield Armory’s Erskine S. Allin to adapt .58-caliber 1861 muzzleloaders to fire cartridges. Activated by a thumb latch, the hinged breech-block popped up to free a fired case and accept the next cartridge. Each required 56 machining operations, cost $5, and in 1866 defined the Army’s first breech-loader. Early .50-70 barrels were bored to .64, then sleeved and chambered for the .50-70 Musket. In 1873, the conversion was barreled to .45-70, the Army’s last black-powder cartridge.

Though fond of Winchester’s 1873 repeater in .44-40, Cody stuck with his single-shot .50-70 for hunting, naming it Lucretia Borgia after the femme fatale of an Italian opera. The standard load burned 70 grains of Fg black powder to drive a 450-grain bullet 1,260 fps. A “carbine load” used 47 grains of Fg and a 400-grain bullet, its mild recoil less likely to unseat cavalry. The later .45-70 rifle load sent a 405-grain bullet at 1,285 fps, for just under 1,500 ft-lbs of energy at the muzzle, same as the standard .50-70 load.

The buffalo-hunting contest drew bets on Comstock from Fort Wallace, while Fort Hays soldiers laid money on Cody. A difference in hunting tactics appeared instantly. Cody dashed ahead, killing at the front of each herd, so animals behind turned from the mounting carcasses. The beasts were forced, then, to run in circles, becoming easy targets that didn’t tire the horse on a chase. Comstock “coursed” herds, firing as he overtook. At day’s end, his 46 kills were strung over three miles of prairie. Cody’s 69 died in groups.

Dangerous Game Medicine

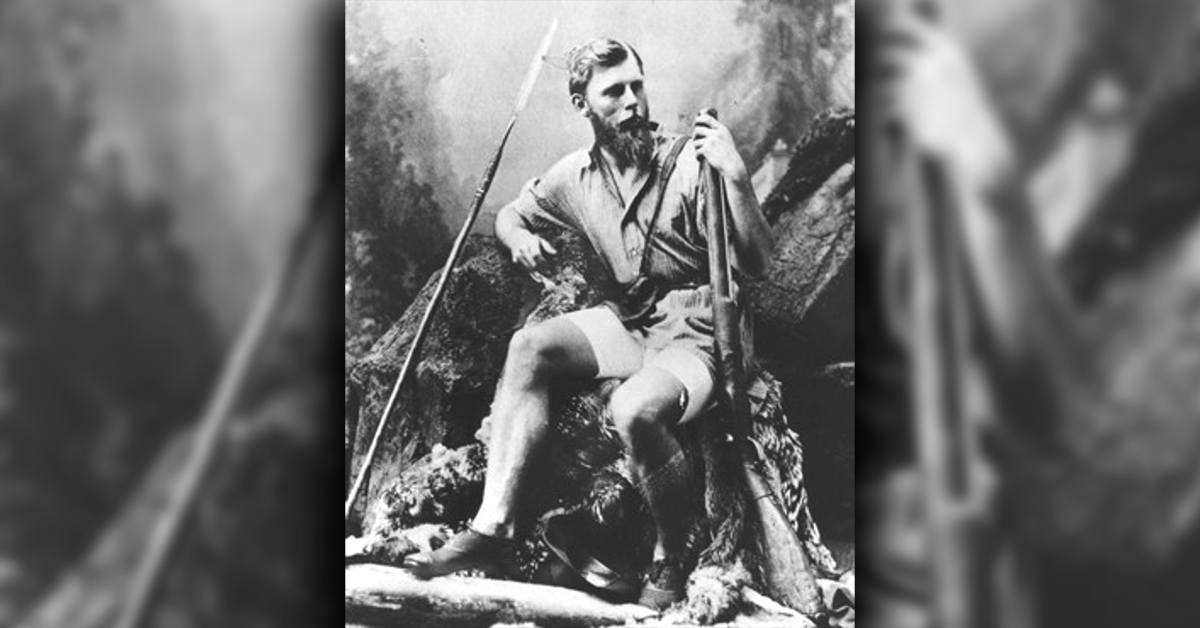

In Africa during the 1870s, ivory hunters were chipping away less dramatically at elephant herds. Many of these men were young adventurers from British families of means. Some used military postings to bring them to rich game fields. Others simply traded the confines of western Europe for the romance of frontiers beyond Mombasa. Ronaleyn Gordon-Cumming provided inspiration with his 1850 book Five Years of a Hunter’s Life in the Far Interior of South Africa. In 1843, after serving as a soldier in India, this giant, raw-boned Scot had sailed to South Africa to seek his fortune in ivory. Using a 4-bore muzzleloader but preferring a two-groove 10-bore Dickson double, he downed 105 tuskers over his short career. “Red Rory” Gordon-Cumming succumbed to heart disease in 1866, soon after building a museum for his trophies in Scotland. He was 46.

A 4-bore sounds monstrous, but it was a common arm early on the ivory trail. Breech pressures, thus the velocities of balls and bullets, were limited by black powder and steels of the day. To deal harder blows, hunters sent bigger, heavier projectiles. “Bore,” like our “gauge,” was the number of lead balls the diameter of the barrel’s interior that would total a pound in weight. A 4-bore muzzle-loader ordered by 19-year-old Samuel Baker from George Gibbs in 1840 burned 16 drams (437 grains) of black powder to thrust its 4-ounce (1,750-grain) silk-patched lead ball from a two-groove, 36-inch barrel.

At 21 pounds, Baker’s gun still kicked brutally. A 12-dram load in another 4-bore broke a recoil-measuring device with a 200 ft-lb. limit! Some big-gun buffs note that for a given projectile and velocity, a charge of black powder kicks about 20 percent harder than smokeless. A rifle used by elephant hunter William Finaughty, who shot about 400 tuskers, sold three times after he retired it. In 1875, the last owner hung 3 pounds of lead on the barrel to limit its climb upon discharge! For all that violence, even hardened lead balls, lethal from the side, didn’t always drive deep enough to kill from the front.

In truth, smoothbore muzzleloaders of this size sold better than rifles. Fine accuracy was hardly needed for close shots at elephants. Rifling twist in smaller bores ran steep; some London barrel-makers wouldn’t rifle 4-bores with twist slow enough to protect the patch under forces imposed by charges stiff enough to stop an elephant. W.W. Greener advised against rifling barrels bigger than 8-bore.

Later “Black Powder Express” cartridges fired conical bullets from breech-loaders. The .450/400 BPE sent 270-grain missiles at 1,650 fps. Then in the 1890s, “Nitro Express” cartridges added thump with smokeless Cordite. Jeffery’s .450/400 3-inch NE drove 400-grain bullets at 2,100 fps.

Sir Samuel Baker would favor rifles from the gun-shop former tobacconist Harris Holland started in 1835. His nephew Henry was a partner six years later. In 1876, “H. Holland” gave way to “Holland & Holland” as the company name. Baker’s celebrated career blessed the shop. Soon after his death in 1893, Cordite powder in Nitro Express cartridges would wring two tons of energy from 400-grain .40-caliber bullets, half a ton more from 500-grain .45s, all at velocities of about 2,150 fps from nimble double rifles.

Hunters of Renown

Ivory markets, and roads and rail lines snaking into elephant country, drew a tide of hunters in the last quarter of the 19th century. Frederick Lokes Slous (original spelling), a banker and chair of London’s Stock Exchange, sired Frederick Courtney Selous in 1851. A budding naturalist, Selous was nabbed at 18 for stealing buzzard eggs and fled Prussia to avoid prison. In 1871, he left London for Africa. In his first three years there, he shot 78 elephants with a 4-bore muzzleloader, then took up a 10-bore cartridge, a .461 Farquharson, and a .450 Black Powder Express.

Selous also hunted across Europe, and North America to Alaska. He joined Roosevelt’s 1909-1910 safari in British East Africa. Having weathered the hazards of mountain and bush for four decades, Selous fell to a German sniper January 4, 1917, scouting on the Rufiji River for the 25th Royal Fusiliers.

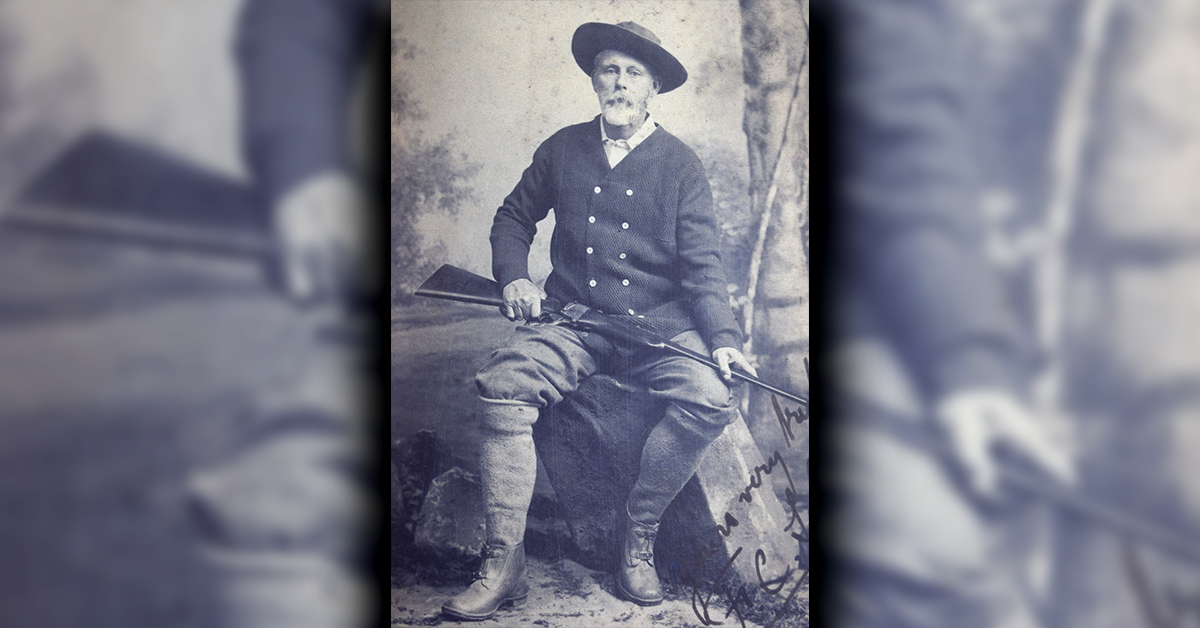

Walter Dalrymple Maitland Bell was born into a prosperous family near Edinburgh. He lost his mother at age two, his father at six. But the eight children wanted for little. Gordon-Cumming’s writings spurred him toward adventure. Brought home by local constabulary after running off “to shoot buffalo in America,” young Bell got farther on a barque bound for Australia. Working his way to New Zealand on a paddle steamer, he returned to Scotland on a refrigerator ship. He was 14. Short years later, his despairing kin sent him to Africa.

Bell arrived in Mombasa in 1897. He shot lions for rail crews building the Uganda line, then took up with a lad in a hunting partnership. It failed. Denied family funds, Bell made his way to the Yukon in the gold rush of 1898. With a fellow Scot, he paddled the Yukon River to Dawson City, where he earned $10 a day shoveling ore. When another partnership crumbled, he sold his rifle for 5 pounds to buy a horse so he could join Canadian recruits shipping off to the Boer War. Captured, he escaped, fattened his purse in Scotland, then returned to Africa. In 1901, with a safari crew of 100, Bell steamed across Lake Victoria to hunt in Uganda. The Karamojong people were awed by his marksmanship. One six-month foray would produce 354 tusks from 180 elephants, felled by cartridges like the .303 British.

Unlike big lead bullets, he wrote, “the solid nickel-jacketed bullet of the .303 [drove the vitals.] Meat food – Africa’s greatest lack – became abundant through the [miracle] of a firearm without smoke [As] tons of meat were provided in a single encounter with an elephant … everyone was happy.”

Short Magazine Lee-Enfields and .303 ammunition were cheap, ubiquitous, and reliable, so Bell and other hunters gave them plenty of play. Bell reportedly killed at least 200 elephants with the standard 215-grain full-jacket military load — though he wasn’t the first to lean on the .303 for that purpose. Arthur Neumann used a Lee-Metford rifle for years before Bell began collecting ivory.

Dismissing the Big-Bores

Most of Bell’s elephants, perhaps totaling 1,500, fell to the .275 Rigby (7×57 Mauser) cartridge. The heaviest 7mm bullets commonly listed were 173- to 175-grain round-nose solids. Bell credited his fondness for the .275 to the reliability of German loads sending these at about 2,300 fps.

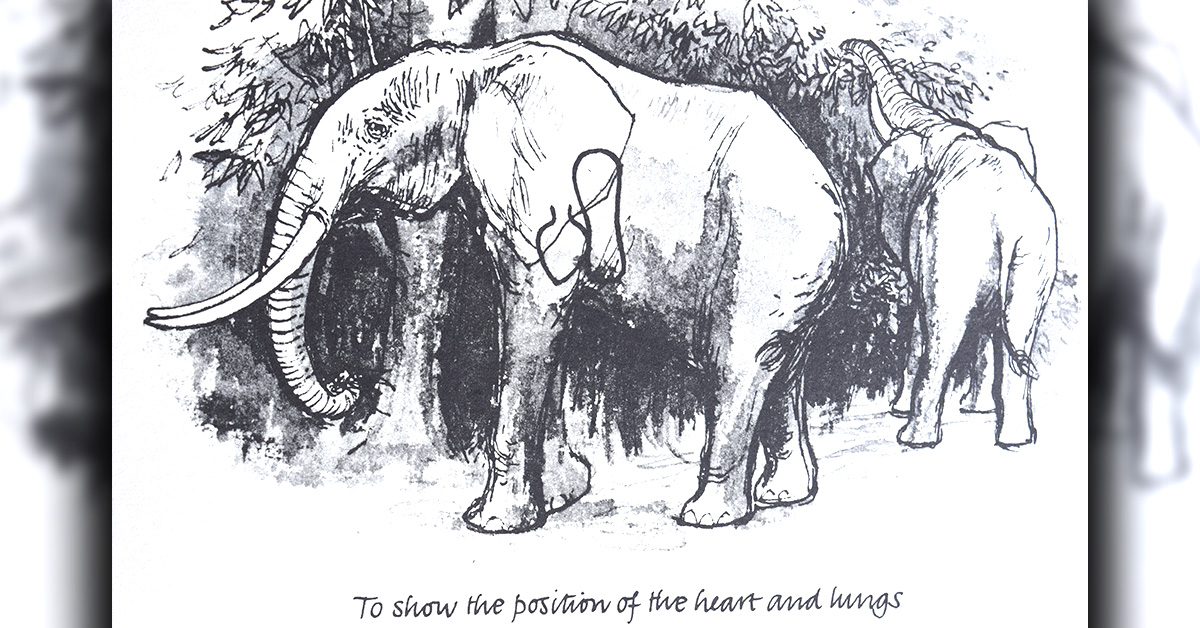

While early ivory hunters pursued elephants horseback, that method was impractical in thick bush where the beasts retreated. Bell hunted mainly on foot, sneaking close so he could place bullets precisely. The magazine and mild report of a small-bore rifle might enable him to drop several elephants when the ivory warranted. In tall grass from a ladder or a dead elephant, or a tracker’s shoulders, he could ill afford stiff recoil. “For the [hunting] which appeals to me most, the light calibres are undoubtedly superior.”

Not that he hadn’t tried powerful doubles. He recalled a .450-400 as beautiful but heavy. “It was slow for the third and succeeding shots; it was noisy; the cartridges weighed too much…” Sand, grit, or vegetation that sifted from elephant hides onto foliage then to breech faces, impaired rifle function.

The lethality of Bell’s small-caliber bullets lay mainly in their high sectional density: the ratio of the bullet’s weight in pounds to the square of its diameter in inches. For any given diameter, the heavier a bullet, the higher its SD and the deeper its penetration. SDs of his .256, .275, and .303 bullets, respectively .328, .310, and .316, are higher than the SDs of all but the heaviest bullets in those diameters now. His long, round-nose missiles drove deeper than shorter bullets and stayed on track better than those with pointed noses.

By comparison, the 405-grain bullets Cody used in his Lucretia Borgia have an SD of only .276. The 200-grain bullet of Winchester’s .44-40 is a miserable .155.

Of course, Bell’s storied marksmanship and his close studies and sketching of elephant anatomy had much to do with his success, as did Buffalo Bill’s horsemanship and deft handling of Lucretia Borgia in the saddle. Where the bullet goes still matters more than its diameter, weight, or speed.