They look fast standing still. They fly flat. Why would any hunter instead use blunt bullets?

by Wayne van Zwoll

At bullet’s impact, the buffalo spun toward me. Through the dust, I sent another. It nicked a horn en route to the shoulder. The beast turned mid-gallop, then crashed to earth as my last shot broke its neck.

All three of those 9.3×62 bullets—a softnose and two solids—had round noses, and for good reason. A round-nose bullet is heavier than a pointed bullet of the same length because nose taper exacts a cost in material. The only way to add weight to a pointed bullet is to make it longer. And length is limited by the rifle’s action, magazine, and rifling twist.

Bullets heavy for their diameter have high sectional density (SD). In a number, SD is commonly a bullet’s mass (weight) divided by its diameter squared: M/D2. Alternatively, it is mass divided by cross-sectional area: M/R2 x pi. (Yes, the results differ, by a constant ratio).

For any given weight, the slimmer the bullet, the higher its SD. A 300-grain .375 bullet has an SD of .305; a 300-grain .458 bullet’s is .204.

Last year, hunting Cape buffalo, I wanted long blunt bullets because high SD contributes to deep penetration in tough game.

OK, I was hunting in thickets with iron sights, expecting close shots. Aren’t pointed bullets much more effective at long range? And isn’t most game lighter and less durable than buffalo? Yes and yes. But excluding Africa’s dangerous beasts, most game taken on my hunts have fallen within easy range of blunt or semi-spitzer bullets. Average shot distance for a dozen deer and elk and African plains animals the last four years: 103 yards. A deer killed at 300 yards by a 115-grain Nosler Ballistic Tip from my .25-06 was an outlier. The deep penetration of blunt, high-SD bullets more often salvaged a hunt. Crawling toward a blue wildebeest bull in thorn, I had only a quartering shot when he rose. A blunt 196-grain softnose from my iron-sighted 8×57 drove from the flank, through paunch and vitals, to the off shoulder.

What is a “high” SD? My arbitrary number is .300. Bullets meeting this mark have served hunters and armies well. Here’s a roster of corresponding bullet weights.

Bullet diameter/weight / SD (M/diameter squared)

- .264 (6.5mm): 160-grain / .328

- .284 (7mm): 175-grain /.310

- .308: 200-grain /.301

- .308: 220-grain /.331

- .311 (.303 British): 215-grain /.316

- .323 (8mm): 220-grain /.301

- .338: 250-grain /.313

- .338: 275-grain /.348

- .358: 275-grain /.306

- .366 (9.3mm): 286-grain /.305

- .366 (9.3mm): 300-grain /.320

- .375: 300-grain /.305

- .416: 400-grain /.330

- .458: 500-grain /.341

Bullets started out blunt, partly because sharp noses were hard to craft, partly because iron sights and the velocities dictated by black powder limited practical shooting distances. Smokeless propellants and stronger rifle steels and actions hiked bullet speeds. Still, military bullets at the turn of the last century were blunt, long, and heavy: 156 grains for the 6.5×54 M-S and 6.5×55 Swedish, 173 grains for the 7×57. The .303 British fired 215-grain bullets, the 8×57 Mauser 220s. Hunters found they drove deeper and in a straighter path than did lighter, faster spitzers. There was no reason to trade their killing effect for flatter travel beyond common shot distances.

Arguably, the same logic should apply today. If memory serves, all but one of the elk that fell to my pointed bullets in 47 years of hunting could have been taken as handily by round-nose or semi-spitzer missiles. In a decade of guiding hunters, I can’t recall a shot too long for a round-nose bullet—or a hunter who used one!

Depending on a handful of variables, long, sharp bullet noses (and tapered heels) start showing an edge at 350 yards or so. Apostles of the high ballistic coefficient (BC) have little use for bullets at lesser yardage, so to them, sleek, pointed profiles make perfect sense. But like sirens of Greek and Roman myth, high BCs come with caveats.

Not all rifle actions, throats, and magazines welcome long bullets. Deeper seating in the case eats powder space. New “long-range” cartridges like the 6.5 Creedmoor have short base-to-shoulder measure to give the neck full purchase on the bullet shank and hew to cartridge-overall-length standards.

Long, slim noses limit options for making bullets expand and penetrate in game. Jacket thickness, amount of exposed lead, and the cavity size of hollowpoints are constrained near the tip. Sharp noses may also behave less predictably than round lead-core noses. Engineers chafe under the burden of fashioning bullets that open reliably at low impact speeds but retain their integrity to penetrate after a violent landing. Swift CEO Bill Hober insists the Scirocco upsets at speeds down to 1,440 fps. Federal’s Jared Kutney has as much to say about the Terminal Ascent. Jeremy Millard at Hornady points out the difficulty of making a pointed copper nose peel at such a gait “without paring BC and inviting disintegration at 3,000 fps.”

Bullets with long noses require faster rifling twist to stabilize them in flight. Until quite recently, standard twist rates worked for any bullet because the heaviest were all blunt. Fast-twist barrels arrived for the .223 (initially loaded with 55-grain bullets) as match-bullet weights crept to 80 grains. Early Sisk 70-grain semi-spitzer hunting bullets weren’t much longer than pointed 53s. But sleeker Pinocchio-nose bullets tumbled when fired from standard 1-in-14 rifling. As lead-free bullets are longer for their weight than jacketed lead, twist rates become critical at a lighter threshold. An accurate rifle I fed solid-copper 55-grain bullets wouldn’t keep them inside a grapefruit at 100 yards. Now .223 barrels come with twist as fast as 1-in-7 ½. Increasingly, long-range bullets of all diameters are labeled for steep rifling. Ignore that caution and your bullets will find disparate paths, some entering targets sideways (keyholing).

Despite their extended noses, only the heaviest long-range bullets boast an SD of .300. Hornady’s 212-grain .308 ELD-X has an SD of .319. That of Berger’s 195-grain 7mm EOL Elite is .345.

The pointed bullet’s faithful hail its shallow arc, its defiance of wind and drag. Some dismiss flat- and round-nose bullets, even semi-spitzers, as ballistic incompetents. “Quick as they clear the muzzle, they’re lookin’ for dirt.” But honestly, at the ranges most game is shot, differences in arc, wind drift, and retained energy are minor. Many round-nose bullets with SDs of .300 or so fly flat enough for 200-yard zeros and a point-blank range (distance at which they stay within 3 vertical inches of sight-line) beyond 230 yards. This list from Bausch & Lomb, old enough to bring a twinge of nostalgia, shows the reach of loads commonly thought to have short leashes.

Bullet; Zero range (yds.); Maximum point-blank range (yds.)

- 5×55 Swedish, 156-gr.; 209; 245

- 7×57 Mauser, 175-gr.; 201; 235

- .280 Remington, 165-gr.; 228; 266

- .30-40 Krag, 220 gr.; 185; 217

- .300 Savage, 180-gr.; 190; 222

- .308 Winchester, 200-gr.; 203 ; 238

- .30-06, 220-gr.; 197; 230

- .300 H&H Mag., 220-gr.; 217; 254

- .303 British, 215-gr.; 182; 213

- .338 Win. Mag., 250-gr. ; 221; 259

- .348 Winchester, 250-gr.; 186 ; 216

- .358 Winchester, 250-gr.; 187 ; 219

- .375 H&H Mag., 300-gr.; 226; 264

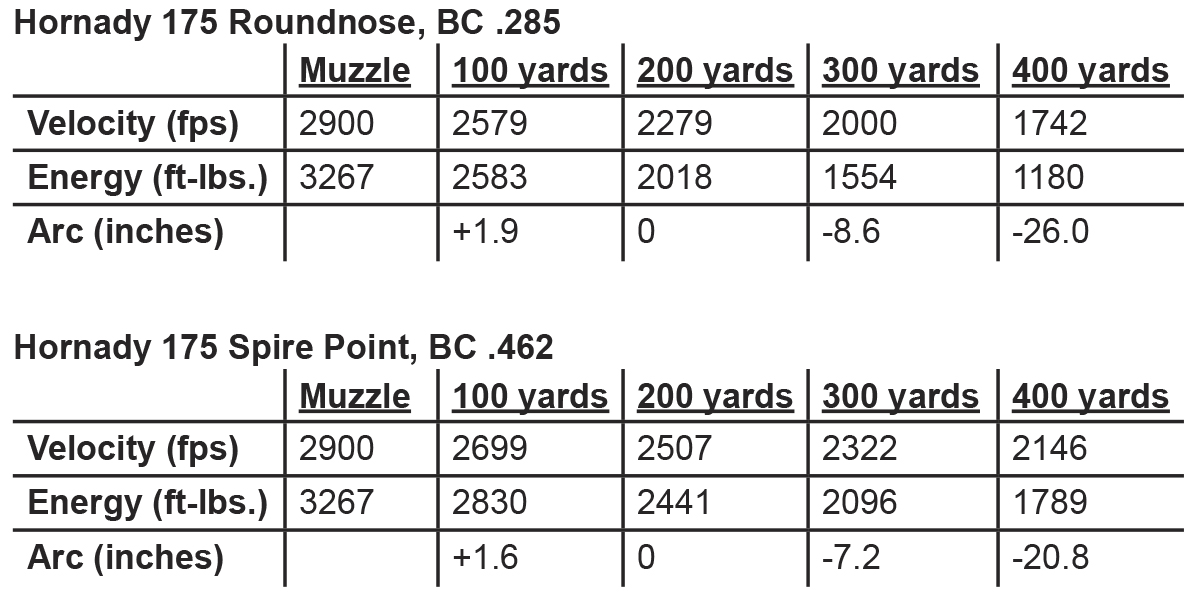

The arcs of blunt bullets from modern rifles are not “steep as a cow’s face.” Consider 175-grain 7mms, round-nose and pointed, each with an SD of .310, fired from a 7mm Remington Magnum rifle:

An element of blunt-bullet design seldom mentioned is weight distribution. Jack Carter tended to it when designing his Trophy Bonded Bear Claw. A thick copper base kept the bullet’s center of gravity near the middle, limiting precession—movement of nose or tail off the shank’s rotational axis. As a top wobbles until its spin “puts it to sleep,” so a bullet shudders about its axis or direction until spin erases it. A round nose counters this off-axis rotation better than does a long nose that shoves CG farther behind the middle. Diminishing in-flight wobble is one reason some loads print better groups (in minutes of angle) at 200 or 300 yards than they do at 100.

Which bullet shape is most accurate? Bullet-makers tell me to mind the tolerances. Dimensions for Sierra’s Pro-Hunter flat-base and GameKing boat-tail bullets are held within .0005 at the base, .0015 at the nose. Tip run-out limit is .0001, weight tolerance .3 grain. Given accurate rifles and practical shot distances, blunt and semi-spitzer bullets made to those standards deliver exceedingly tight groups.

At this writing, I’m planning an elk hunt with a carbine in .303 Savage, not commercially loaded for decades. My handloads send 170-grain flat-points at around 2,100 fps. Handicapped? Well, I won’t be firing at elk 300 yards off. But a 180-grain round-nose Core-Lokt leaving at 2,400 downed my last bull at 140 steps, as far as I’ll stretch this carbine’s iron sights.

In fact, I find little appeal in firing at game beyond the effective reach of round-nose bullets.

Plight of the Sphericals

What about patched round balls? Unlike conical bullets, lead balls of a given diameter have only one weight, one SD value. A .490 (50-caliber) ball weighs 177 grains; a .535 (54-caliber) ball weighs 230. SDs are dismal: .105 and .115. A fully mushroomed lead-core bullet has an SD approaching that of a lead ball; so, a bullet is best designed so full upset leaves some shank (weight, inertia, momentum) to help push the bullet through the vitals. That shank will also maintain spin, to encourage straight travel.

Bouncing Through the Bushes

Both pointed and blunt bullets deflect in brush. Any difference is hard to prove, as trials require duplicate strike angles and resistance. Northwest hunter and writer Francis Sell fired enough bullets into typical blacktail cover to conclude nose shape was less a deflection factor than bullet weight and speed. He found bullets of reasonably high SD at around 2,500 fps (and given plenty of spin) deflected least. In my trials, with paper backers 12 feet behind targets, 3/8-inch sage limbs turned all missiles, including 1-ounce 12-bore shotgun slugs. High SD appeared to help keep bullets on course at velocities of 2,400 to 2,800 fps.