How a barrel is made affects the accuracy it delivers. But can babying a new bore improve it?

by Wayne van Zwoll

It wasn’t very attractive. Its rubbery gray stock was little more rigid than a garden hose — suitably matched to a barrel that looked as whippy. The plastic trigger guard and shapeless recoil pad also told of a rifle built to a price point. But the whole was in new condition, and I had just enough jack in my jeans to pay cash. I took it to the counter.

Expecting groups the size of summer squash, I was astonished when, under an unimpressive 4x scope, this rifle put three factory-loaded .300 Winchester Magnum bullets in a nickel-size knot. Following shots held as tight. No super-duper match loads. No break-in voodoo for the bore.

Why does this homely urchin still shoot better than costlier blue-bloods in my rack? Barrel-maker John Krieger of Krieger Barrels says I was lucky. “That barrel is performing above its price, perhaps because of its internal structure.” He told me steel has grain and inclusions. These affect not only its integrity but how it reacts to the stresses of heat-treating, boring, and rifling. Structural variation means barrels made the same way at the same place from steel of the same source aren’t always identical when finished.

Re-rifling worn-out barrels, Bill Atkinson concluded that the raw steel can affect accuracy before it’s cut. A heavy .222 Benchrest barrel won so consistently that when its accuracy at last faded, the owner had Bill bore it out to .308. Its groups again topped the score board, one setting a world record!

Barrel-makers and competitive shooters generally agree that both chrome-moly and stainless steel can produce barrels that shoot into one hole. The steel must be hard enough to wear well but not so hard as to preclude machining to close tolerances. Of course, bores must be straight and uniform.

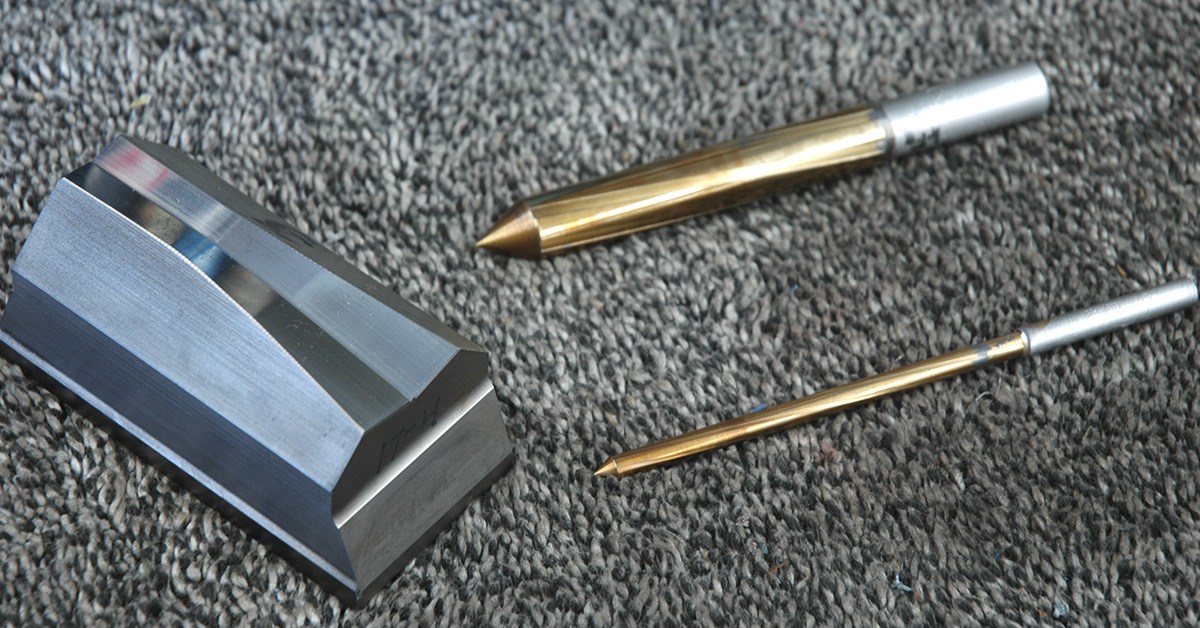

Rifling — the type and how it’s formed and finished — has a big affect on accuracy. Button rifling, commonly used on .22 rimfire barrels but popular, too, with Benchrest shooters, “irons” grooves into the bore with a carbide plug. As it doesn’t remove material, it’s similar to hammer forging, which “kneads” a thick-walled blank around a hard mandrel with rifling in reverse. The barrel emerges longer, more slender and of desired contour. Cut rifling first appeared in Nuremburg late in the 15th century. A bore-diameter cylinder with a hook is pulled by a rod through the bore, shaving about .0001 inch per pass and indexing to cut or deepen the next groove. A rotation setting determines twist rate. John Krieger likes this method. “Rifling with a single-point cutter is slow and costly but imposes little stress on the blank,” he says. It can also produce superior accuracy, as his barrels and those from H-S Precision have proven.

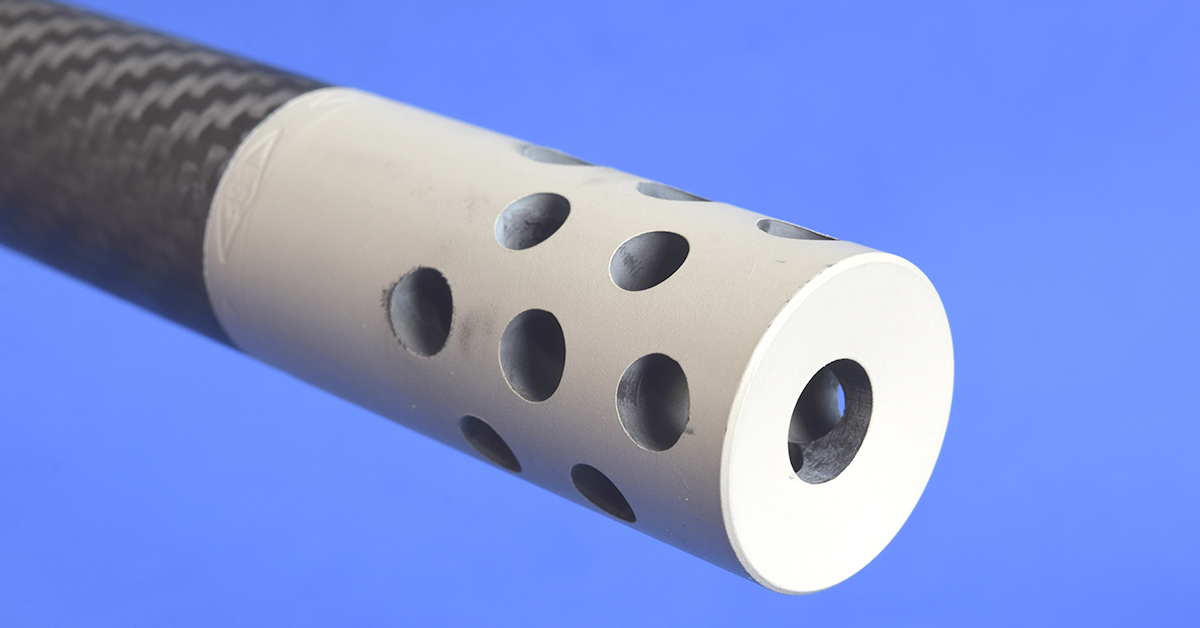

Accurate barrels have been produced with a range of rifling configurations. There’s no “perfect” groove shape, number, or depth. Late 03A3 Springfields with two-groove rifling have shot very well. So have Marlin .22s with Micro-Groove barrels, initially with 16 grooves just .0008 inch deep! Bullets exit with less distortion from shallow grooves and narrow lands; but these don’t endure the friction of high-velocity jacketed bullets as well as does more aggressive rifling. Most current centerfire rifles have four, five, or six grooves. Five-groove 5R rifling limits friction and fouling with a gentle groove-to-land angle.

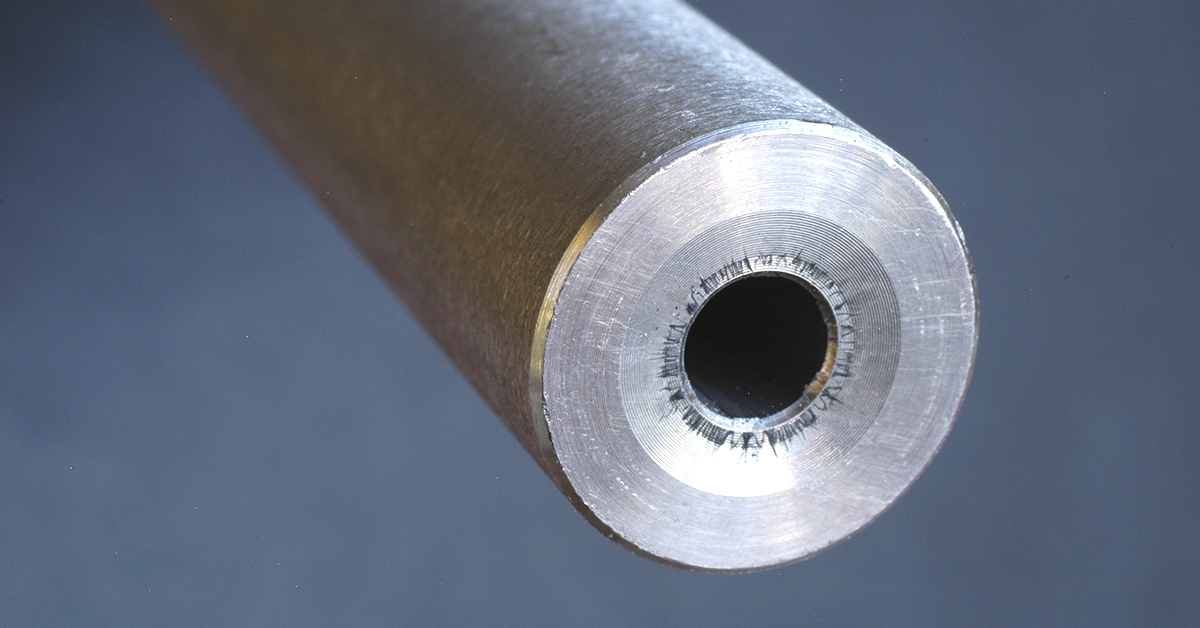

Bore finish affects accuracy, too. Yes, “smooth” is good. But it’s a relative term and can apply to a surface ripple of 10 to 20 micro-inches, which some barrel-makers prefer. A glass-smooth surface can increase friction, as you’d feel pressing one prism face across the surface of another. A bullet engraved by the lands as it starts down the bore is pressed (and distorted) into full contact with it.

“Lapping” helps ensure a smooth bore. Abrasive compound on a lead plug run repeatedly through the barrel polishes out microscopic tooling marks. Lapping adds time and expense to barrel production so is not routine in factories. Barrel-makers like Kenny Jarrett insist on it. For me, Jarrett barrels on hunting rifles have shot like the best match barrels, lapped or not! Arguably, a more important function of lapping is to remove tight spots, ensuring the bore is of uniform dimensions, throat to muzzle. Bill Wiseman’s test barrels for the industry are button-rifled, then lapped. “Uniformity matters more than surface finish, as regards accuracy,” he says, but points out that “lapping removes only about .0002, so it won’t fix gross errors in deep-hole drilling or rifling.”

Bore uniformity is most precisely checked with an air gauge. A probe moved down the bore uses air pressure to “feel out” variance to 50 millionths of an inch! Jarrett, Krieger, and button-rifled Pac-Nor barrels are air-gauged to a tolerance of .0001.

Machining stresses imposed on steel can be “frozen out of it.” Apparently, the process was around as early as 1940, but it wasn’t practical for rifle barrels until 1992, when Pete Paulin found a way to avoid brittle results. “Steel’s crystalline structure changes in fabrication,” he told me. “Later stresses can cause unpredictable expansion and contraction.” Firing a cartridge expands the barrel and stretches it. Paulin’s company, 300 Below, minimizes or eliminates internal changes in barrel steel by bringing it to -300 degrees F. (Absolute zero, or 0 Kelvin, is -457 F; nitrogen liquefies at -323 F). “Cryo won’t ever degrade accuracy,” he told me. “Usually there’s a visible improvement.”

Some barrel-makers use both Cryo and lapping; some use neither. Procedures vary. Steve Dahlke laps Criterion barrels after stress-relieving and outside turning. John Krieger laps his cut-rifled barrels to just under 16 micro-inches in the direction of bullet travel, then trims an inch from the muzzle to remove flare that can result from bore finishing.

Barrel Break-In: Myth or Fact?

Given all the technology, tooling, and gauges applied to barrel production, is “breaking in” a new barrel necessary? Many shooters say frequent, thorough cleaning every few shots for the first couple of boxes of ammo, while keeping the barrel from getting hot, leads to better accuracy. Veteran barrel-makers demur. If barrels behave as individuals, comparing groups fired from a conditioned barrel with those from an untreated barrel can’t confirm the effects of break-in, as a real test requires two identical new bores. In practical terms, conclusions can be drawn from repeated trials. H-S Precision manufactures the barrels (as well as stocks and actions) for its tack-driving rifles. Each H-S barrel, declares the company, “has gone through its initial break-in during accuracy testing.” It adds, though, that cleaning a bore every six shots for the first 30 is a good idea.

Thorough, frequent cleaning of a fresh bore removes carbon and copper deposits that can impair accuracy. Copper buildup scars subsequent bullets; accuracy quickly deteriorates.

A bore scope reveals imperfections you won’t see with the unaided eye, or feel with a brush or a patch. It can show advanced fouling in a second-hand rifle, or a fresh wash of copper after your first shots through a new bore. Absent a bore scope, you can get a quick read on accuracy with a few careful shots. (First, give the bore a quick brushing and swabbing to remove grease and anything foreign.) My bargain-basement .300 excelled as it came from the used-gun rack. So did a recent new Marlin .45-70 from Ruger. With Hornady ammo, it put the lie to rumors that lever rifles can’t shoot sub-minute groups! Some barrels yield tighter knots after a few shots, with or without cleaning. Call it in-service lapping, less the abrasive. And freshly cleaned bores often put the first shot of a group out of center. In prone competition, we who wanted to win always fired a couple of “fouling shots” through a clean bore before shooting for record.

Bore Care for the Win

How you care for a rifle’s bore after a trip to the range or field affects its accuracy and longevity more than will any break-in. Still, gently introducing your barrel to 60,000 psi of scorching gas jamming metal down its gullet at Mach 3 is a kind gesture. Kindness is a virtue.

Alterra Arms has outlined a very good bore-cleaning procedure. Repeating it at, say, eight-shot intervals during the first 40 rounds through a barrel seems to me a most worthy break-in routine. Here it is, with tweaks from my experience.

Hold, or better, secure the rifle in a vise or cradle with the muzzle angled down — newspaper below to catch spatter. Wipe a one-piece rod, steel or coated, with an oily cloth to remove dust and grit. Attach a slotted or pointed jag. With a bore guide in the receiver to keep the rod from flexing against the chamber mouth and to ensure sludge from the bore doesn’t enter the action, run a patch soaked in carbon-removing solvent (powder solvent) through the bore. Remove the patch at the muzzle. Repeat with a clean, soaked patch. Replace the jag with a nylon brush, soak that in the same solvent and run it back and forth through the bore. Count 20 passes, adding solvent after 10. (A bronze brush of the proper size won’t wear out your barrel.) Follow with dry patches until they come out clean.

Now, to remove copper fouling, repeat that routine. Soak the patch in Sweet’s copper solvent or a similar ammonia-based solution. Ditto with a new nylon brush. Keep ammonia-based solvents from your rifle’s mechanism, exterior steel, and stock! A rag over the rifle’s stock comb wards off tiny droplets from the emerging brush. After 20 passes with the brush, leave the wet bore for five minutes, then swab it with dry patches. A blue or green stain on a new patch indicates copper fouling. If so, brush again. Getting new patches to come out white as a sheet in a laundry commercial can be difficult. Fret not. Oil in your truck’s engine is darker than when it came from the jug. There’s probably toothpaste on your bathroom mirror.

Clean the chamber by inserting a powder-solvent-soaked brush that fits loosely (a tight fit won’t let you remove it!) and rotating it. I often wrap a soaked shotgun patch on a brush to do this. Follow with dry patches. Before storing the rifle, swab the bore with a patch soaked in light oil, then one dry patch.

Of Salt and Water

Before smokeless propellants blessed the 1890s, black powder left bores looking like chimneys. But rifling wasn’t torched by high-pressure gas or charred by friction from fast bullets. It was spared the corrosive effects of potassium chlorate, added to primers for hotter spark. (Earlier, mercury fulminate in priming had helped ignite stubborn smokeless powder; but it ate cartridge brass, a result exacerbated by lack of absorbent black powder residue.) To prevent rust forming after use of potassium chlorate primers in smokeless loads, shooters scrubbed bores with boiling water and ammonia or baking soda. The heat and a finishing patch dried the bore; an oily patch protected it.

Non-corrosive, non-mercuric priming followed work by German chemists at RWS in 1901. J.E. Burns at Remington developed “Kleanbore” priming in 1927. On its heels: Peters “Rustless,” Winchester “Staynless.” While powder and primer residues from current U.S. sporting ammo won’t harm barrel steel, they’re hygroscopic. They draw moisture. Fired or not, a rifle carried afield merits a couple of passes each evening with oiled, then dry patches. Mind the chamber! As sudden warmth condenses moisture on steel, a rifle fresh from a day in sub-freezing cold is best kept in a cool place — under your cot in the tent or cabin, or in a vehicle outside.