A $36 optic was once state-of-the-art. What you need costs more now. So do features you don’t.

by Wayne van Zwoll

Optical sights appeared a couple of centuries after Galileo and Lippershay built telescopes to see stars. By the 1850s, target shooters were peering at milky images in barrel-length tubes later used by Civil War snipers. In 1901, the J. Stevens Tool Co. acquired the Cataract Tool and Optical Co., following with Stevens rifle scopes. Engineers at Zeiss/Hensoldt in Germany listed a compact “prism” scope three years later. By the late 1920s, Zeiss owned Hensoldt and was working on variable power!

U.S. scope-makers proliferated during the Depression. In 1930, young Bill Weaver announced his Model 330, a 10-ounce sight with a 3/4-inch steel tube and internal windage/elevation (W/E) adjustments. Grancel Fitz hunted all species of North American game from the ’30s into the ’50s with a Griffin & Howe Springfield wearing a Hensoldt 2 ¾X Zeilklein This 8-ounce optic with a 22mm (7/8-inch) tube had generous, non-critical eye-relief. In 1939 it cost $36.

About then, a Zeiss engineer got brighter images by coating lenses with magnesium fluoride. Fog-free scopes came in 1949, with Leupold & Stevens sealing nitrogen in scope tubes. Oddly, these improvements barely tickled prices! A post-war Zeiss cost just $11 more than its Depression-era forebear; a 4X Unertl in 1950 brought $2 less than Noske’s 4X in ’39!

Until the ’50s, reticles moved about in the field during W/E adjustment. So clever engineers put an erector pivot at the tube’s rear, where the reticle was positioned. In 1962, a year after Leupold announced its Vari-X 3-9X, Lyman began fitting its All American scopes with Perma-Center reticles.

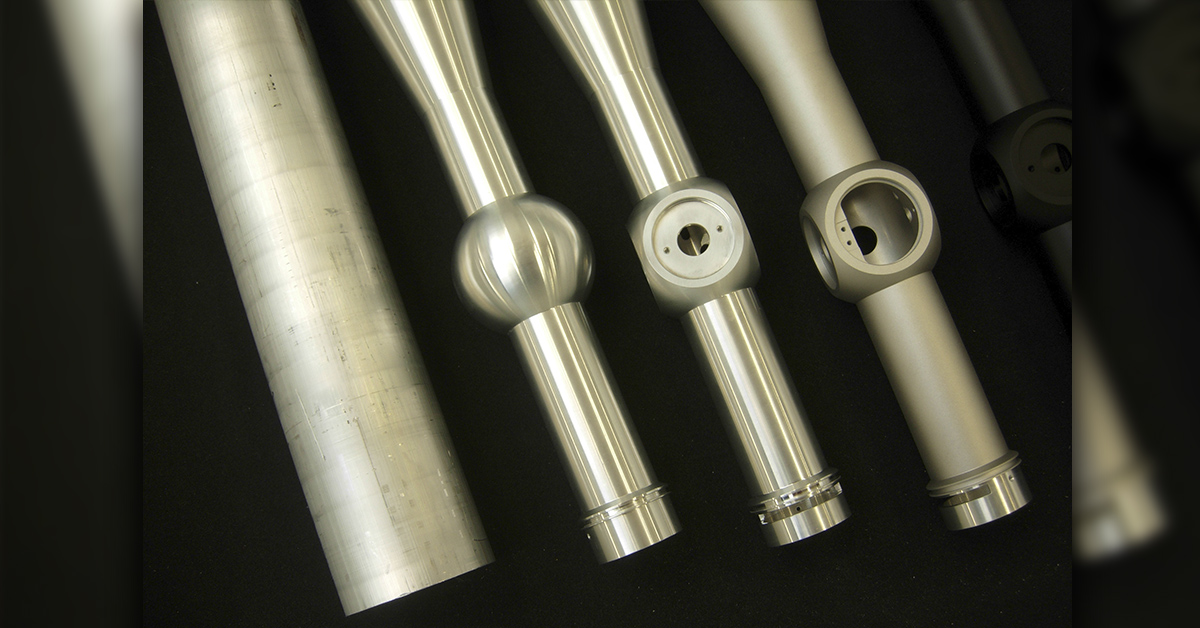

Developments since include one-piece tubes CNC-machined from thick-walled tubing. Horsehair and T.K. Lee’s .008-inch dot-on-spider-web reticles acceded to Leupold’s Duplex: .0012 platinum wire flattened to .0004. Meopta uses chromium oxide to produce etched reticles—UV light through a template exposing all but the reticle on the photo-sensitized lens. After a wash, only the reticle remains.

The magnesium fluoride that reduced reflection and refraction on Zeiss lens surfaces in the 1930s has been replaced by multiple compounds that affect multiple wavelengths. Meopta applies 13 on its fully multi-coated lenses. (“Fully” means every lens surface). Additional coatings like the Zeiss LotuTec slip water for clear aim in rain or snow. Bushnell’s RainGuard has given way to Exo Barrier. It repels oil and dust, too, and erases breath-fogging. Leupold Diamondcoat resists scratching.

Not all improvements are visible. I’m told Swarovski buys about 100 types of task-specific glass. Complex scopes beg tight manufacturing tolerances, some gauged by lasers. At Swarovski, prism flatness is held to 1/100,000 mm, light angles to 1 ½ seconds. Finished Zeiss lens surfaces are so closely matched, they “stick” by vacuum pressure when joined by hand.

Machinery and software in scope factories is frightfully expensive. So, too, is skilled labor. In its lens production and fitting section, Meopta employs 900 people. Forty coating machines include eight Syrus units worth 1.2 million Euros each! Research, development, and patents cost years and Euros.

The most sophisticated scopes now retail for 100 times the price of my first scope. Are they that much better than a $39 Bushnell? No. But a costly optic may help you make a crucial shot at a records-book animal or win in competition. To spend wisely, consider first those features you must have—fully multi-coated lenses, repeatable W/E adjustments, useful magnification range. Durability matters. You’ll want enough free tube to place rings where you wish.

Early variable scopes had three-times ranges (top magnification three times the bottom). Six-and eight-times ranges now tempt shooters, few of whom need spin a power dial that far. Distant steel rewards magnification. I used a fixed 20X for years. It would serve well for PRS matches now. Hunting, you may want a 3X in cover, the precision of 6X, even 8X at distance. Only twice have I used more power on game.

Optical gurus tell me wide power ranges can require additional lenses to correct for aberrations as each lens works harder. Lenses in six-times scopes travel twice as far as in three-times, so parts variations can have twice the effect.

“Tolerances run to half a thousandth for erector cams,” says a Leupold engineer. “Vignetting increases. Sharp focus becomes hard to maintain; parallax hard to control. Costs climb.”

Fast-focus eyepieces are becoming standard, like seatbelts in automobiles. Presumably, you’ll not need either often. An eyepiece focuses the reticle to your eye; you re-set it only when age changes your vision.

Big front (objective) glass boosts resolution, but not noticeably over smaller lenses of like quality. They add brightness only at high magnification and in dim conditions. Exit pupil, the diameter of the light shaft reaching your eye, is a ratio: lens diameter in mm divided by magnification. A 42mm lens at 6X has a 7mm EP—roughly your eye’s maximum dilation at night. At noon, your eye can’t use that much light. Reducing magnification hikes EP without adding the bulk, weight, and expense imposed by big glass.

Scope tubes of great girth (34mm to 40mm) offer little benefit and require costly rings. They’re heavy, too. A Swarovski dS 5-25×52 with a 40mm tube weighs 38 ounces. A 34mm Vortex Razor HD 4.5-27×56 scales 48 ounces.

Trajectory-matched elevation dials cut and scribed for specific loads let you “dial the distance.” Lasering a target at 600 yards, you dial to “6” and hold for center. Some scopes are now offered with one custom TM dial. W/E dials with zero stops and rotation indicators are helpful in long-range matches.

Range-finding reticles went digital in 2018, when SIG Electro Optics announced its BDX system. First, you transfer ballistic data from a smart-phone app to a BDX Kilo laser rangefinder and “bond” your BDX scope to that rangefinder. Then you can range any target with the Kilo and aim with the lighted dot that appears on the scope’s reticle. As there’s no laser in the scope, BDX is legal for hunting in all states.

Illuminated reticles can speed aim in dark or “busy” cover, but they’re expensive and, excepting Trijicons, require a battery.

An adjustable objective or left-side turret dial corrects for parallax and sharpens target focus at a distance you choose. Most hunting scopes without such an adjustment are set for zero parallax at 150 yards. At other distances, if you move your eye off the scope’s axis, you’ll see target shift behind the reticle. With your eye properly centered, there’s no parallax error at any distance.

Outsourced production in the Far East has greased entry into the scope market and grown scope series within brands. Leupold lists over 60 rifle scopes for hunters. Vortex has 54 catalog pages of scopes.

Retail prices help you comparison-shop, but “street prices” of optics commonly undercut MSRP.

An on-line source recently offered a $1,100 Vortex Razor HD at $900. Bargains abound in the crowded 3-9X arena, where competition is fierce. Not long ago, a $329 Burris Fullfield E1 appeared at under $200.

Mid-priced scopes can offer fine quality and include most features. Buyers are wising up. At a Cabela’s store last year, I counted 180 scopes priced from $50 to $3,000.

“Great optics, those,” said the clerk, nodding to the 13 tagged at over $1,000. “I dust ’em every week.”