The pump rifle dates almost as far back as lever-actions. This model upstaged most of them.

by Wayne van Zwoll

A deer rifle can be any rifle you take on a deer hunt. But the image that pops up for many hunters is that of an iron-sighted lever-action carbine. Winchester’s 1894 and Marlin’s 1893 in .30 W.C.F. were hugely popular as smokeless powder replaced black. Their progeny, the Models 94 and 336, earned equal billing in whitetail woods. A market lean to optical sights, and pointed bullets reaching Mach 3, relegated many traditional deer guns to the mantel. Still, flat-sided carbines endured. And not all were lever-actions.

Winchester’s first lever rifle, the 1866, arrived just 18 years before Colt’s slide-action Lightning. Chamberings in this “pump” ran to .50-95 Express! The Lightning with that long action died in 1894; and within a decade Colt dropped the model. But Remington engineers would revive the slide mechanism. In 1912, it announced the hammerless Model 14.

At that time, almost all deer fell at modest ranges, in cover. Tree stands on the fringe of cropland were still decades away. A hunter’s only chance might be a fleeting poke at a running buck. He wanted a rifle that jumped to cheek and delivered follow-up shots quickly.

Larry Benoit, of Vermont, grew up in that era. He and the men in his family would gain celebrity for their ability to track big deer in the big woods and bring those bucks to bag. While Larry learned early the ways of whitetails, he wasn’t always well-armed hunting them.

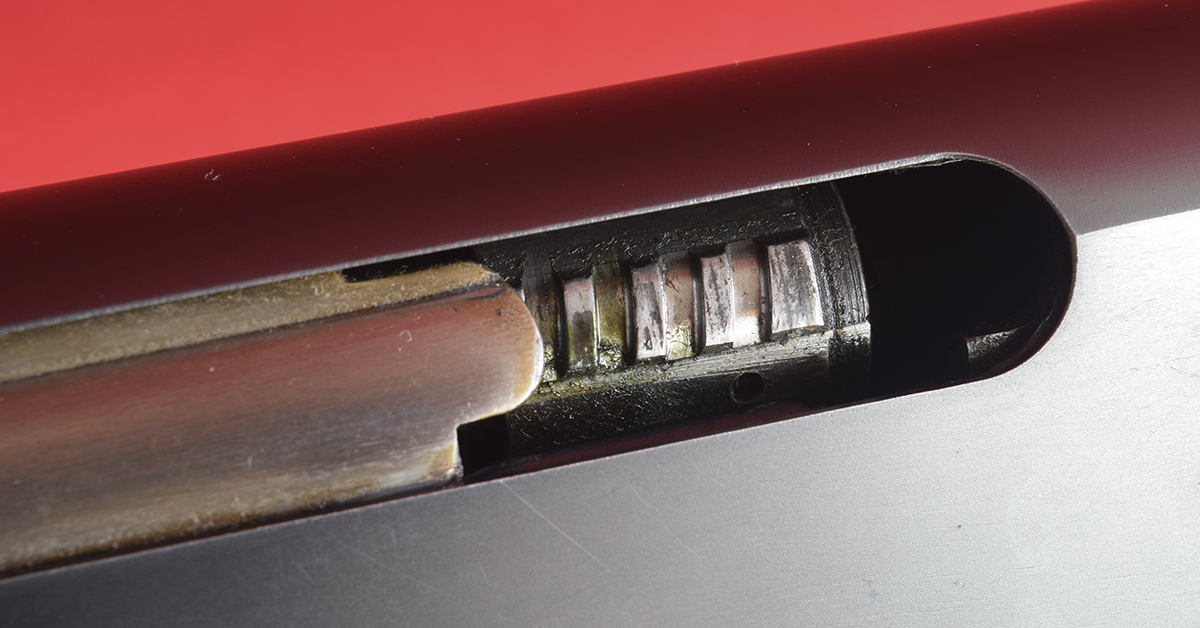

“My first deer rifle was a .25 Stevens Crackshot,” he recalled in a book he published with Peter Miller in 1975. He replaced the .25 with a .45-70 trapdoor Springfield — more potent, but still a hand-me-down single-shot. Larry made the leap to repeaters with a Remington Model 14 in .32 Remington. By the time he started hunting deer, at age 9 in 1933, Remington had manufactured that rifle for 21 years — and was months away from dropping it. Chambered to the .25, .30, .32, and .35 Remington, it was also known as the 14A. The 14 ½ (14 ½ A) was bored to the aging .38-40 and .44-40. Both rifles had 22-inch barrels. Carbine versions with 18 ½-inch barrels got an “R” suffix.

In 1935, Remington followed the 14 with the 141. Like its predecessor, it appeared as a rifle and a carbine (the rifle with a 24-inch barrel). A few .25s were made during its debut year, but most 141s are in .30, .32 and .35. The pistol-grip butt-stock and grooved forend, more substantial than the walnut on the Model 14, made the rifle more comfortable in recoil and easier to control. Higher grades were listed — C (Special), D (Peerless), and F (Premier) — with fancy checkered wood and fine engraving. Demand from the deer woods kept the 141 in production until 1950.

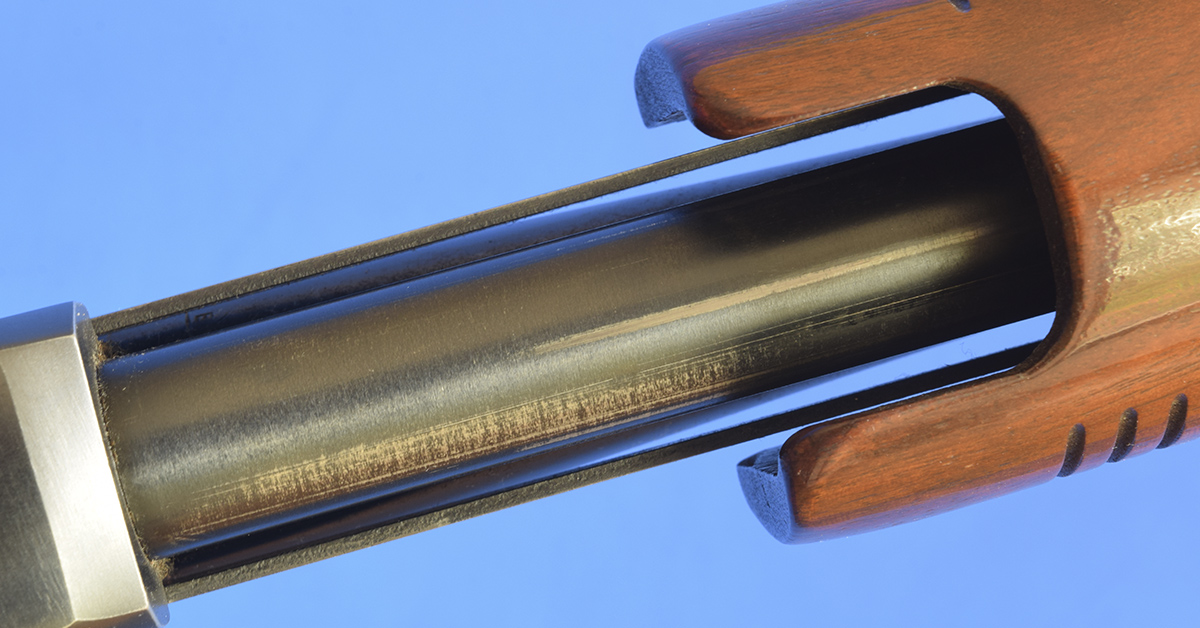

Two years later, Remington trotted out the 141’s replacement, the 760 Gamemaster. Developed by L.R. Crittendon and William Gail, Jr., the 760 had twin action bars, a detachable box magazine, and a rotating, multiple-lug bolt that locked into its 22-inch barrel. It bottled pressures of the .270, .30-06, and .308. The .300 Savage was also a charter number. Of Model 141 chamberings, the .35 Remington alone was held over. It would endure 15 years in the 760.

Two other cartridges that pre-date the 760 were added to the roster: the .257 Roberts and the .222 Remington. The .244 and .280 Remington joined after they appeared in the 1950s, the .223 in 1964. Only a handful of listed rounds would last until the 760 left Remington’s line in 1980.

The 760 Carbine, with an 18 ½-inch barrel, came only in .270, .280, .30-06, .308, and .35 Remington.

A CDL Deluxe Carbine, manufactured 1961-63, was not listed in .35. Oddly enough, Remington did offer it in 760 ADL and 760 BDL rifles (along with several other standard chamberings), and in the top-end D- and F-grade rifles.

When dropped in 1981, the 760 Gamemaster had sold over a million copies. Remington replaced it that year with the 7600, which had a more angular look, with a press-checkered stock and a high comb.

Larry Benoit retired his Model 14 to buy a Remington 760 in .270. He would replace that with a 760 Carbine in .30-06. Son Lanny took a similar route, lopping the barrel of his 760, a .270, to 19 inches. “Lanny and I feel [these pumps] are the most reliable in all conditions,” wrote Larry. “They are light and can take rough use… The Remington 760 is accurate [too]. I plugged a moose in Newfoundland at 400 yards — all three shots were centered in the rib cage.”

Larry used a Williams receiver sight to bag that moose. He preferred it to a scope — and without the screw-in aperture. Up front, he installed a Williams ivory bead that rode “higher than the [standard] front sight… You want the bead to float high above the base [so it’s] isolated.” After snowfall, he painted the bead with red nail polish so he could see it instantly against a white background. Larry thought hunters using scopes should stick with a 2 ½x. But: “Personally, I think a scope can cost you your buck because it is so slow to pick up on a running deer. It also raises the weight of your rifle.”

Like other serious deer hunters, Larry wasn’t above whittling on the stock to make sure his 760 fit him perfectly. Many of his best bucks were taken “on the jump” as he came close on a track. His Carbine — 6 ¾ pounds trailside — had to respond as if he were firing at a grouse with a fitted smoothbore.

I’ve owned a few 760s. I like the way they come to cheek. They feel much like my short-barreled Remington 870 shotgun of the same era and similar profile. The 760s still with me (in .30-06 and .300 Savage) won’t be leaving anytime soon.

The 7600 that supplanted the 760 wasn’t as sleek in profile or as nimble in my hand; however, a colleague in Colorado found it just right for a rifle he would dub his “Pump’r Thump’r.”

An exciting leopard hunt had prompted John Dustin to consider a fast-firing repeater for Africa’s bush. The Blue Book of Gun Values had brought a pump to mind when it listed as-new 7600s at just $710. Any new idea that could save a dime, he’d once opined, is worth testing. Soon he had a 7600 on the way.

“It’ll be a stopping rifle for the Big Five,” he told me on the phone, pausing for effect.

Now, the 7600’s mechanism can’t digest cartridges the size of the .375 H&H, widely considered — and in many places designated by law — a minimum round for a stopping rifle. I pointed this out, adding that pumps have no published record in Africa. “They’re un-British. Besides, you can’t tell me a pump is as reliable as….”

“My Pump’r Thump’r won’t be a magnum. But it will be reliable. And a lot faster with five shots than a bolt gun.” He figured he could launch a bullet with two tons of energy from a 7600 — “about what you get with a 300-grain solid from a .375 H&H.”

“How on earth can you do that?” I figured he was itching to explain — also that this pump would be ferocious. I was right on both counts.

Remington had once barreled the 7600 in .35 Whelen, which could be necked up to .375. But the similar 9.3×62, a European round dating to 1905, had five grains more capacity. Bumped from .366 to .375 and loaded to maximum (magazine) length of 3.34 inches, it was the better choice. Dave Skiff at Pacific Tool and Gauge made a reamer for John’s wildcat. Hornady sent custom dies.

John had attacked the rifle as soon as it arrived, shaving the stock’s comb for iron-sight use. A Pachmayr Decelerator pad brought length of pull to 14 inches. He opened the forend for a thicker barrel.

The .375 Pac-Nor #5 barrel he chose was “heavy enough to tame muzzle jump and recoil.” Soon after chambering and fitting, he added his own JD Quietbrake, installed a Williams ramp front sight and ordered an XS rear aperture for the Weaver scope base securing his Burris 1.5-6x in low rings. A trigger job readied his Pump’r Thump’r for the range.

“Hornady’s dies worked perfectly with a variety of bullets,” John reported. “And I tried a bunch!” He settled on 300-grain Sierra GameKings for thin-skinned game, pushing them to 2,450 fps with a stiff charge of Varget. “They fly flat and bring 2,500 ft-lbs to 350 yards.” They’d kill buffalo with lung shots, but John wanted solid-bullet loads, too. He got them with 300-grain Woodleighs and Hornadys.

John coated all bullets with molybdenum disulphide, confiding that uncoated bullets would call for reductions in his powder charges to keep pressures reasonable.

As he intended to use his rifle on dangerous game, he practiced firing fast offhand — “five aimed shots in six seconds” at close-cover distance. “I set five clay pigeons in a dirt bank 30 yards out and broke them all in eight seconds,” he told me. “That’s 20,000 ft-lbs of heavy-bullet energy, faster than you or I can dish ’em out with a bolt rifle or a double. And the Pump’r Thump’r is lots cheaper.”

Next test: Elephant.

In parts of Zimbabwe, elephants are so numerous they’re routinely culled by government rangers. John got a permit for a tuskless animal. His chance came on the trail of a small herd. Reeling in the final yards, his PH confirmed the lead cow had no tusks. “I eased ahead to get a clear shot,” John recalled. The animal faced him at just 15 steps. He triggered the powerful rifle, sending a Hornady DGS through her brain. She collapsed. “I ran up and fired an insurance shot, but it wasn’t necessary. The first bullet had exited the rear of the skull. We recovered the second. It had smashed through the 8-inch spine and traveled the depth of the elephant undamaged. I could have reloaded it!”

In other action, the Pump’r Thump’r would prove it had the punch and reliability to qualify as a stopping rifle — performance that might not have surprised the legions of hunters who’d bet their hunting seasons on Remington 760s.