The .44 WCF fed Winchester’s 1873 rifle. In Colt revolvers, it filled more gun belts…and coffins.

by Wayne van Zwoll

Shoved toward the vault, Myers considered his options. The voice behind the revolver was flat. “Open it.” Time crawled. The tellers were worlds away. Silent faces. Collateral. His fingers shook. The dial clicked. Back. And again. “Inside.” There’d be no second chance…

George Arrowsmith must have seen profit in Walter Hunt’s “Volitional Repeater.” He bought all patent rights and hired Lewis Jennings to refine the lever-action rifle. But it proved a problem child, and Arrowsmith soon peddled it for $100,000 to fellow New Yorker Courtland Palmer, who’d made a fortune in rail and hardware investments. Palmer paid Horace Smith and Daniel Wesson to improve on the rifle’s externally primed “Rocket Ball,” a bullet with the powder in its hollow base. They added a primed copper case. Palmer put $10,000 toward a partnership. A year later, in 1855, a group of 40 investors bought out Smith, Wesson, and Palmer. Oliver Fisher Winchester became director of a new Volcanic Repeating Arms Company. When flagging sales sent Volcanic into receivership in 1857, he snatched all assets for $40,000 and hired Benjamin Tyler Henry to revive the Hunt-Jennings rifle under the shingle of New Haven Arms Company. In 1860, Henry patented his work.

Though Winchester hawked the Henry to the Army as a “terrible engine [that would] enable any government…to rule the world,” few rifles saw action in the Civil War. Those that did, however, made an impression. A Confederate rifleman recounted his 1864 capture after he and three companions chased down one Union soldier with a Henry. Ordered to halt, the man turned and fired “simultaneously with us. One of our group fell dead… The rest of us proceeded to load, when he again fired twice…killing two more of my comrades…I had my gun loaded and a cap [ready, but] I dropped both…”

Ballistically anemic, the Henry charmed with its firepower. Winchester claimed the rifle would fire 15 shots in 15 seconds “or [double-time] at a rate of 120 shots per minute…” The rifle held 17 rounds, the carbine 12. Nevada City Marshal Steve Venard brandished his Henry when he accosted three men who’d robbed a stage. They reportedly resisted arrest. Four shots toppled them all. Wells Fargo gave Venard a cash reward and an inscribed Henry.

In 1866 B. Tyler Henry left New Haven Arms. His successor Nelson King gave the Henry a receiver loading port and a wooden forend. The resulting Model ’66 was first in a series of lever-actions from a new Winchester Repeating Arms Company. Its .44 rimfire round fired a 200-grain bullet from a 28-grain charge.

Beginning in 1867, after the factory’s move to Bridgeport, Winchester shipped 100,000 Model 66s in six years. During the Franco-Prussian War in 1870-71, France bought 6,000 of them, plus and 4.5 million .44 Henry cartridges. At the same time, the Ottoman Empire purchased 50,000 ’66 rifles and carbines.

Winchester followed the ’66 with the Model 1873, on a steel instead of a brass frame. It chambered Winchester’s first centerfire cartridge. The .44 Winchester Center Fire (WCF) or .44-40, burned 40 grains of black powder to hurl a 200-grain bullet at 1,310 fps. The ’73 later added the .38 WCF (.38-40, in 1880) and .32 WCF (.32-20, in ‘82). William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody declared, in 1875, “For general hunting or Indian fighting I pronounce your improved Winchester [’73] the boss… An Indian will give more for one of your guns than [for all others].” The ’73 was listed in rifle and carbine form (24- and 20-inch barrels), and, to draw military contracts, as a full-stock rifled musket.

Two other notable firearms claim an 1873 birth: the “trap door” Springfield rifle in .45-70 and Colt’s Single Action Army revolver, in .45 Colt. The U.S. Army snatched both for regular duty. Winchester’s rifle also served, less broadly. It became best known in motion pictures. In 1950, Anthony Mann directed “Winchester ’73” starring James Stewart and Shelley Winters. (To promote it, Universal launched a public hunt for 136 Winchester ’73 rifles marked “1 of 1,000” at the factory for their exceptional accuracy and finish.) John Ford delivered “Rio Grande” with John Wayne and Maureen O’Hara. William Castle’s “The Gun That Won the West” featured Dennis Morgan as Jim Bridger and Robert Bice as Red Cloud. Film titles puffing Colt’s SAA (or Frontier Model P) are oddly absent, though it has served screen heroes from Hart to Eastwood.

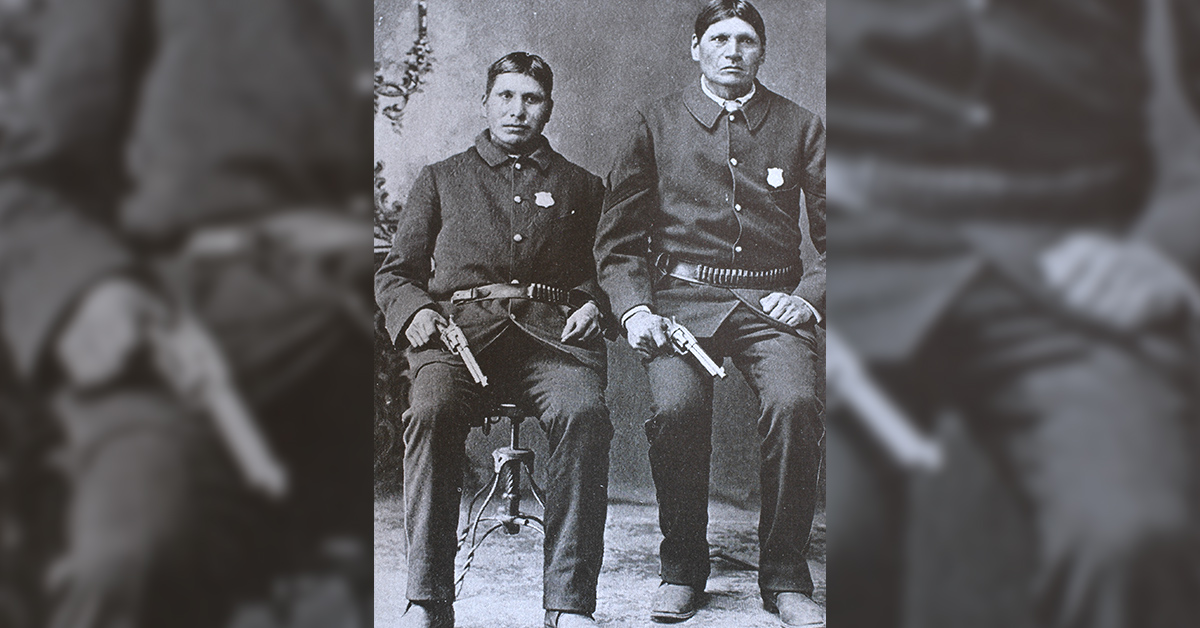

After the Civil War, many damaged young men brought violence west with their Winchesters and Colts. Law officers cinched belts and saddles heavy with the same hardware. Settlers armed themselves likewise to protect their families and livelihoods.

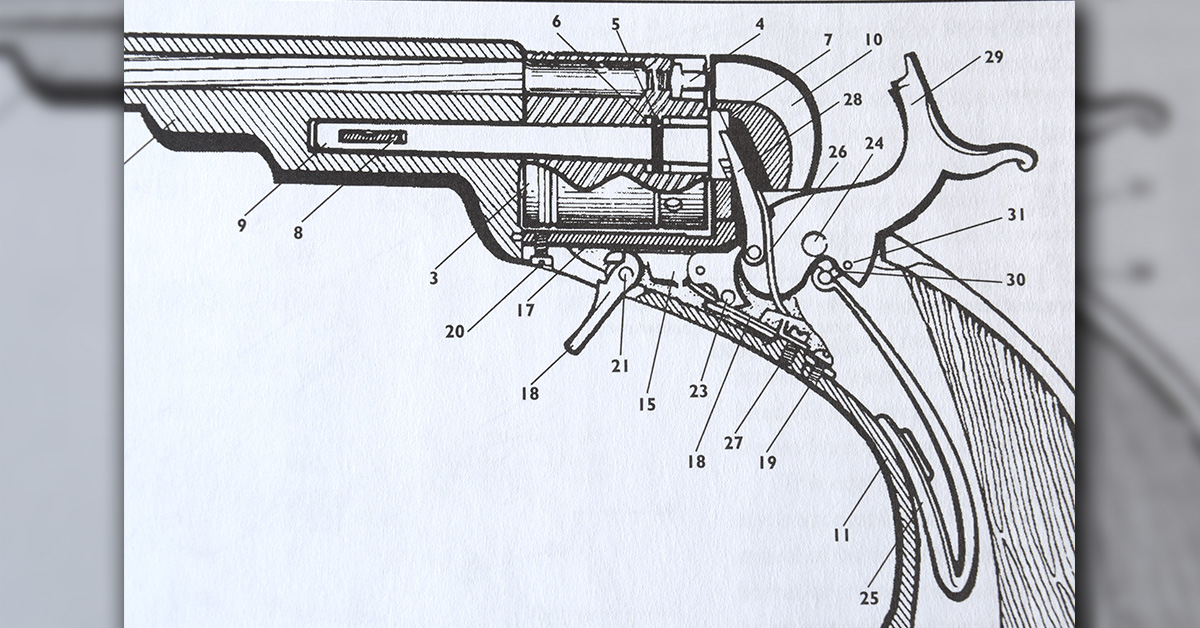

Less powerful than frothy rounds for single-shot “buffalo rifles,” the .44-40 quickly became popular in repeaters. Winchester profited; other rifle-makers took note. The 1883 Colt-Burgess lever-action came in .44-40, as did Colt’s 1885 Lightning slide-action. In 1878, Colt offered it in the SAA revolver. The .44-40’s bullet couldn’t quite match the punch of the .45 Colt with its slightly slower 255-grain .452 missile. But as a common chambering for the two most popular guns on the frontier — Winchester and Colt Models of 1873 — the .44-40 became a star.

The .45 Colt, with its five-year head start, held on as top seller in revolvers. A stunning 42 percent of early SAAs were so chambered. The .44-40 finished second in sales, at 18 percent. During its first decades, Colt’s plow-handled single-action all but owned the handgun market. Remington’s 1875 Army in .44-40 and .45 Colt earned its keep but lagged in the proprietary .44 Remington chambering. The only liability of any solid-frame SA: slow reloads. Clearing each chamber with the ejector rod was tedious — and difficult if you were ducking bullets astride a galloping pony. An alternative arrived in Smith & Wesson’s Model 3 in .44 American and .44 Russian. Its top-break mechanism kicked all empties out at once. Major George Schofield urged tweaking the S&W for cavalry use. While ammo for the Schofield revolver functioned in an SAA, the reverse was not true. The Army demurred.

Excepting Colt’s .45, the .44-40 had little competition in black-powder revolvers. It was said to have “killed more people, good and bad, than any other cartridge.” An unprovable, if not unreasonable claim. Winchester’s ’73 rode in the scabbards of the Texas Rangers and the RCMP. It remained popular through the 1880s, in wagon boxes of sheepherders and on jungle trails with rag-tag militias in South America.

As smokeless powder replaced black in the 1890s, the .44-40 was blessed with cleaner loads that hewed to pressure limits imposed by thin brass and early rifles and revolvers.

A .44-40 could turn up where least expected. Bail-jumper Henry Starr (later Belle Starr’s brother-in-law) was on the run when he met an ex-deputy named Wilson. Both men fired; both missed. Wilson’s rifle jammed. Starr strode up and shot him. After the U.S. Supreme Court overturned a murder conviction, Starr attempted what the Dalton gang had 23 years earlier. On March 27, 1915, in Stroud, Oklahoma, he and his gang of five split to rob two banks at once. First National capitulated, but cashiers at Stroud State balked. The delay gave 17-year-old Paul Curry, a butcher’s son, time to grab a Winchester. Starr dropped, hit in the thigh. A second bullet mortally wounded another thug. The rest fled.

A recovered Henry Starr proved incorrigible. On February 18, 1921, he and his gang popped up in People’s National Bank, Harrison, Arkansas. Muscled to the vault, Manager William Myers grabbed a ’73 Winchester stashed there. Starr took the bullet in his spine. After surgery, uremic poisoning killed him.

The last of 720,610 Model 1873s shipped in 1924. By then, Winchester was the pre-eminent U.S. firearms company. Browning-designed lever-actions would bring it into the smokeless era. Priced at $18, the Model 1892 chambered the .44-40, also the less powerful .25-20, .32-20, and .38-40. It was an instant hit and stayed in Winchester’s line until 1941. Counting the Models 53 and 65 variants (1924 and ’33), the company shipped more than 1,034,000 Model ’92s. The Marlin 1894 also chambered the .44-40 and other WCF rounds until it faded away in 1934. Remington’s Model 14 ½, a 1913 slide-action, came in .38-40 and .44-40. By 1938, the .44-40 was homeless.

In rifles, that is. But not in revolvers. Colt would keep the .44-40 in its SAA until the U.S. entered WW II. Later, Italian-made Colt reproductions sold stateside by Traditions, Cimarron, and Taylor’s would chamber the .44-40, with new models from Ruger.

The .44-40 lost some of its handgunning faithful to the .44 Special, introduced in 1907 as a zesty alternative to the .44 Russian. The .44-40 case has greater capacity than the .44 Special but isn’t as stout. Some early hulls were of balloon-head design and had mercuric or corrosive priming. Savvy handloaders use new brass, hold pressures to 13,000 c.u.p., and mind the difference in bullet diameters (.429 for the .44 Special and Magnum, .427 for the .44-40).

Black Hills, Hornady, Winchester, and MagTech load .44-40 ammo with 200-grain lead bullets at about 720 fps from 6- and 7 ½-inch barrels. My Cimarron Model P revolver and a Winchester 53 rifle like Cowboy Action loads from Black Hills. Their Starline brass is perfectly crimped. Uniform, flat-nose lead bullets fly with all the accuracy I can bring to the bench. Recoil is modest, shooting fun.

These days, fun is your link to this historical giant, the .44-40.