Founded in Redfield’s long shadow, it equips hunters with practical, affordable, optically fine sights!

by Wayne van Zwoll

In 1971 Don Burris had been working for Redfield as an engineer for over a decade. When he’d come aboard, John Redfield’s widow was still part owner, as was a son, Watt, and Ida Kellogg, his sister. Owen Tytegraff and Ed Hilliard made it a foursome. Redfield had recently acquired Kollmorgen’s Bear Cub scope business and was moving the Massachusetts-headquartered company to Denver.

Burris would contribute much to Redfield — rangefinders and non-magnifying reticles in scopes, also an internally adjustable target scope. Until Redfield’s 3200, small-bore competitors favored Lyman Super-Targetspots that slid in adjustable mounts, with spring-driven return to battery. In college, I scraped up $100 for a second-hand 3200. It would bring me two state prone titles. I should have gone in hock for a pallet of those scopes!

In the summer of 1970, Ed Hilliard died in a mountain-climbing accident. That event nudged Don Burris to chase his dream of founding his own scope company. The next year, he left Redfield. Established in the spring of 1972, his enterprise would prosper in Greeley, east of Denver. Don envisioned improvements to make his scopes superior: bigger fields of view, more repeatable adjustments — also better seals, checked by immersion in 130-degree water. Burris scopes would be stronger, to brook the stiffest recoil.

In 1975, Burris announced its first three scopes in what Don called a Fullfield line. The 4x, 2-7x, and 3-9x had 1-inch alloy tubes and constantly centered reticles. Big ocular lenses delivered generous fields. The 4x’s 37-foot FOV (at 100 yards) was up to 20 percent larger than those of competing scopes. Burris made mounts, too, the bases and rings interchangeable with Redfields and Leupolds.

A 2 ¾x, a 6x, and a 1 ¾-5x followed. A 10x, a 12x, and a 4-12x were on the roster by 1977. They had adjustable objectives to focus the target and to eliminate parallax error. Hi-Lume multi-coating to boost light transmission in early Burris variables may have been the first such treatment in U.S. scopes. Fully multi-coated glass (all lens surfaces) is now all but standard on rifle-scopes.

As the industry announced ever bigger hunting optics, Burris bucked that trend with three Mini scopes. The 4x, 6x, and 8x weighed around 9 ounces. Only the 8x had a front bell. Despite their compact profiles, they were stoutly built, and with 3.75-inch eye relief, ably served powerful hunting rifles. Next: LER and IER (long- and intermediate-eye-relief) optics for handguns and carbines. In 1981, the company introduced range-compensating reticles.

Don Burris passed in 1987. By then, I was hunting with Burris scopes. Once, in Wyoming, a fine pronghorn appeared through the mirage at well over a quarter-mile. Crouching, I scooted along a route to bring me within 200 yards. But shortly, in a prairie depression, I came upon other pronghorns at slingshot range. I couldn’t skirt them. Far beyond, the buck was feeding away.

My .280 was accurate; I had used it at long range. So, prone, I consulted the scope’s new Ballistic Plex, a wonderfully simple and useful reticle with three tics intelligently spaced at 6 o’clock on a standard plex wire. For popular loads, the tics correspond to point of impact at 200, 300, and 400 yards with a 100-yard zero. The measures between them increase down the reticle, as bullet arcs are parabolic. The 17 inches of bullet drop between the “300” and “400” tics is roughly the chest depth of a big deer or a pronghorn. Ranging the buck at just shy of 400 yards, I aimed with the lowest tic.

That prairie goat is still my best.

Burris scopes are tough, too. Once, checking zeroes with a pal in a pasture, I trotted out to change the 200-yard target. My friend hopped in his truck to paint steel at 400. He didn’t see my rifle on the mat where I’d been firing prone. He drove over its comb, tang, and receiver, and the scope’s eyepiece. Mashed into the mat, stock splintered and lever bent, that .30-30 was hardly the picture of health! Several wraps of duct tape bonded stock shards. With tire tools we freed the action. Surprisingly, the scope appeared intact. I bellied down, hoping its innards weren’t so damaged or the eyepiece so skewed it wouldn’t zero. The rifle, to my relief, stayed together. The bullet, to my astonishment, not only struck paper, but the center of the target! The half-ton truck hadn’t shifted the Burris’s zero at all! I later killed two animals with that rifle. Its action was stiff; but it sent bullets unerringly to point of aim.

At that time, no one predicted fixed-power scopes would go the way of the dodo — or surely I’d have bought several Burris offerings, like the 6x atop my Cooper in .17 HMR. It’s a slim, lightweight optic, and brilliant. But the market craved variables. Burris obliged.

One of my favorites is the Fullfield E1 on my short-barreled Tikka T3 in .308. Just 12 ounces and 11 ½ inches long, this 1-inch scope is a perfect fit. Its 35mm objective lets it sit low. It boasts a “floating” Ballistic Plex E1 reticle and 3 ½ inches of eye relief. Its magnification range is more than broad enough. In 50 years of hunting, I’ve never wanted less than 2x, and only twice needed more than 7x. Alas, Burris has dropped the 2-7x; but other E1s remain: 3-9×40, 4.5-14×42, and 6.5-20×50. The 13-ounce 3-9×40 lists for just $191.99. The 4.5-14×42 has a focus/parallax dial, weighs two ounces more. At $287, it seems a bargain.

The recent 1-inch Fullfield IV stable comprises five scopes, including a 2.5-10×42 and a 3-12×42 (with focus/parallax dial) that scale 17 ounces. Priced at $228 and $300, respectively, they offer the value Don Burris intended for hunters.

Few scopes are designed expressly for nimble, close-cover rifles. The market has swung to 30mm tubes, higher magnification, wider power ranges, more features. Burris’ Veracity line goes there without going overboard. There’s a 2-10×42, a 3-15×50, a 4-20×50, and a 5-25×50. While my pick is the 2-10×42, the 25-ounce 3-15×50 is arguably the most versatile, suitable for whitetails from tree stands to steel plates out yonder. Burris supplies W/E dials in minutes or mils. The company also offers “FFP” scopes, with a first- or front-focal plane reticle. This reticle appears heavier as you dial up power, thinner as you dial it down. Relative to the target, though, it stays a constant size, for quick range-finding at any power setting.

Burris gives you five-times power range in its 1-inch, 20-ounce Signature HD 3-15×44. From $624, it’s a third less expensive than the Veracity.

The big 39mm to 46mm ocular glass of the E1, Fullfield IV, Signature HD, and Veracity deliver broad FOVs and help you find targets quickly.

About 20 years ago, after steep hikes in production costs, and to keep a lid on prices for Fullfield scopes, Burris supplied tooling and specs to modern optics factories in the Philippines and moved production there. Inspection stayed in Greeley. (Many U.S. optics firms now import components and finished products from the Far East.)

In 1992, Burris added binoculars to its product line. It also notched a Benchrest win in the Hunter Class with its new BR riflescope.

When it was new, I reported on the Burris Eliminator, a 4-12x programmable, laser-ranging riflescope. It instantly registered target distance and, with stored ballistic data for a chosen load, illuminated a dot in the scope’s field. The dot showed where the bullet would land, the scope having compensated for drop. An integral base secured this 26-ounce sight to a Picatinny rail or Weaver bases.

A 3.5-10×40 Eliminator followed, then an Eliminator II 4-12×42. The laser’s range increased. An Eliminator III, 3-12×42 or 4-16×50, read to 1,200 yards on reflective targets, 750 on deer. A few ounces heavier, it wasn’t as bulky. The sleek Eliminator IV and Eliminator 5 scale under 29 ounces, peg targets to 2,000 yards. “The range compensation is accurate,” declared one hunter, who had also tested the scope’s durability. Stalking a mountain goat, he lost his grip on his rifle. It cart-wheeled over a cliff “onto rocks 500 feet below.” With effort he retrieved it. But had the scope lost its zero? He shot at a distant mark. The bullet hit spot on! Still far off, the billy hadn’t moved. “I killed him with my next round. That Eliminator is bomb-proof!” It endures weather extremes, too, and temperatures from -15 to 120 F.

Last I checked, Burris provides drop numbers for more than 1,500 factory loads. With help from a ballistics program (or ballistic coefficient and velocity data), you can add handloads. The Eliminator’s CR2025 battery should last over 5,000 cycles.

Trajectory-matched dials appeared on Burris scopes in 2013, with the C4 (Cartridge Calibrated Custom Clicker) series. Shortly, upgrades yielded the C4 Plus 3-9×40 and 4.5-14×42 sights. Elevation dials tailored to owner-specified loads have since blessed other Burris scopes.

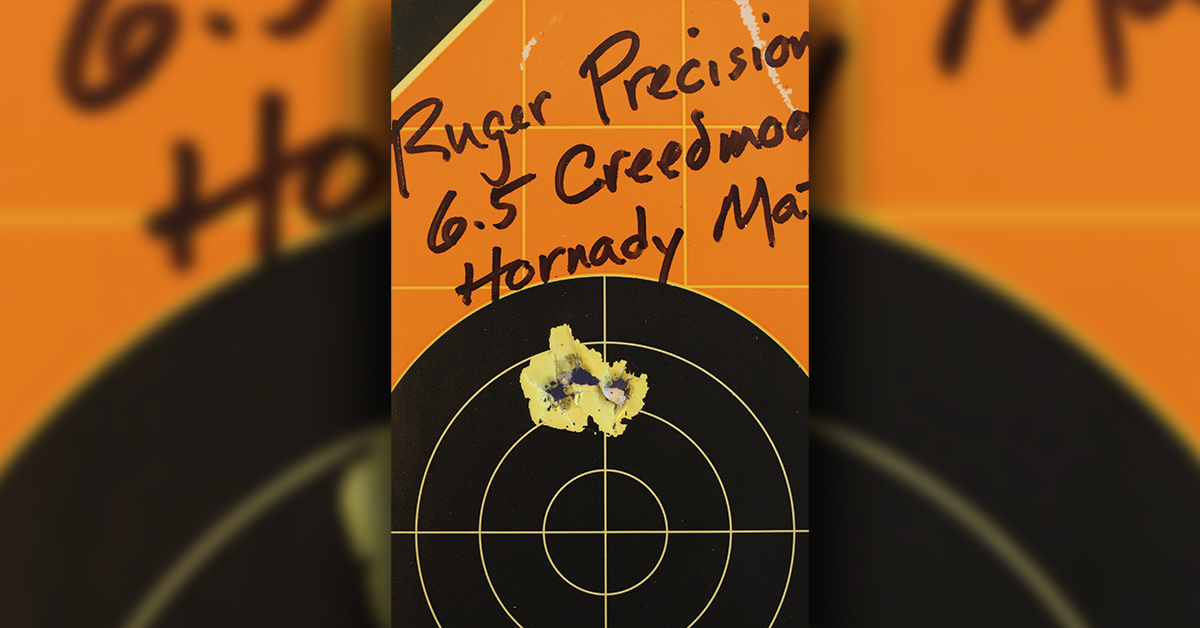

Burris has added Tactical and Thermal scopes to its catalog, also bow-sights. A 34mm XTR II 4-20×50 target scope is on my long-range Ruger RPR in 6.5 Creedmoor. For close-cover deer hunting, I’m sweet on the FastFire 3 red-dot sight, a 1x, 1.5-ounce optic with a 3- or 8-minute dot and three brightness settings. A champ on carbines and shotguns with slugs, it lists for $276.

Burris Signature Pos-Align scope rings belong in any why-didn’t-I-think-of-that file. Horizontally split and secured by Torx screws, these steel ring sets, bright or matte, medium or high, fit any Redfield-style or Weaver base, or grooved rimfire receiver. Thin nylon or polymer inserts ride the radiused inside surface of each ring, correcting for misalignment without stressing or marring the scope.

John Redfield would marvel at the product line offered today by Burris!

The Redfield Connection

Don Burris might have applied his engineering talent at another company. That he chose Redfield was no surprise. I was a youngster then. Dave Bushnell had begun importing scopes from the Orient, but Redfield, Leupold, and Weaver were the foremost U.S. manufacturers of riflescopes. The Redfield brand predated the others.

John Hill Redfield was born on a farm near Glendale, Oregon in 1859. His parents, from Illinois and Connecticut, had reached the Willamette Valley by oxcart. His mother was wounded en route in an Indian attack. With his seven siblings, John grew up when the West was still truly wild. Reportedly a fine shot, he found work as a scout, and as a meat hunter for the Northern Pacific Railroad. He also served as a U.S. Deputy Marshal. His son Watt divulged later that John had been shot four times during that period. In 1894, about a year after partnering with his brother Sam in a gunsmith shop in Medford, John married Ida Wilcox. Moving to Spokane, Washington, he designed the Redfield Rock Drill. That invention pulled him to Denver, where in 1906 he set up shop to produce it for Colorado’s mining boom. As the Cripple Creek lode petered out, John turned his hand to other devices, from a washing machine to a shotgun that could be set at timed intervals to chase coyotes from sheep.

In 1909, John founded the Redfield Gunsight Company in a shop behind his house on 3315 Gilpin Street. Open sights came first. His aperture sights were snapped up by hunters and competitive shooters. John tinkered with a low-powered scope, too. In 1916, he designed a scope mount base with a dovetailed front ring and a rear ring secured by windage screws. Widely copied, it’s still popular. Watt Redfield was active in the business and developed much of the shop’s tooling. He became company president upon his father’s death in 1943.

Owen Tytegraff, who’d joined Redfield as a public relations man in 1934, helped keep it solvent during the Depression. Rifle-scopes later fueled growth that sent Redfield to an 18,000-square-foot shop at 1325 Clarkston Street, then to an 81,000-square-foot factory on East Jewell.

In 1959, Watt Redfield retired and handed the reins to Ed Hilliard, Jr.