Benchrest circuit to ’chuck pastures, winter foxes to chamois in the Alps, the .222 does everything well!

by Wayne van Zwoll

Remington announced our first commercially loaded rimless .22 centerfire round in 1950, even as it unveiled the 870 pump shotgun. Harry Truman was president. I still think kindly of all three, perhaps because their history pretty much parallels mine, or because we’ve yet to improve on them. The cartridge was the .222 or, as it soon became known, the triple deuce. Now, ye who are ready to pounce, I’m aware the .22-250 and .220 Swift pre-date the .222, as do the rimmed .22 Savage High-Power, .22 Hornet, .219 Zipper, and .218 Bee. But in 1950, the .22-250 was still a wildcat, for handloaders only. Remington didn’t adopt it until 1965. And the Swift is semi-rimmed, with a .445 base, a .473 rim.

Remington’s first .222 load drove a 50-grain bullet at an advertised 3,200 fps. It was essentially a match to the Zipper’s 56-grain bullet at 3,110. (With stiff loads in dropping-block single-shots, the Zipper can edge the .222; but as introduced for Winchester’s Model 64 rifle in 1937, the .219 was held to lever-action pressures.)

To shooters of that day, the.222 may have resembled a miniature .30-06, dear to millions. With its 1.7-inch case .378 in diameter at the head, the .222 was shorter and more slender than any rimless big game rounds of that day, whose hulls ranged in length from 1.87 to 2.23 inches and featured the .473 head of the .30-06. It was quickly snatched up by fox hunters torn between the barrel-eating, pelt-pulping Swift and the anemic .22 Hornet. It also caught the attention of Benchrest shooters. It used a small rifle primer, was clearly efficient, and was soon printing tiny groups in matches.

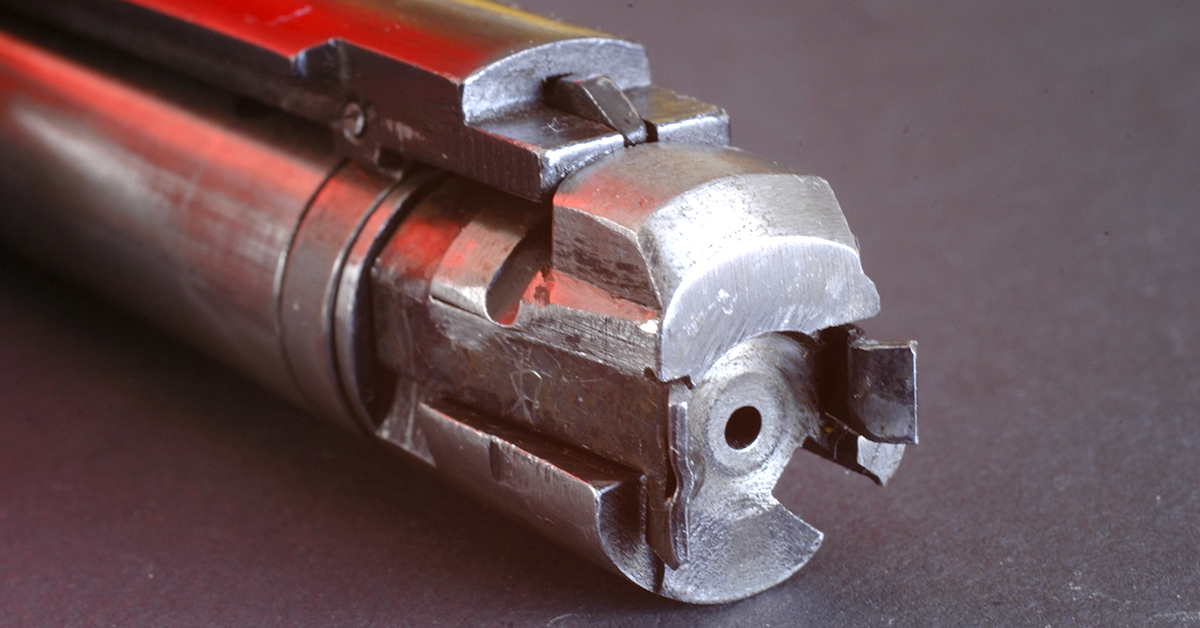

Remington’s 721/722 rifle (long and short tube-steel receivers) was two years old in 1950. Less expensive to manufacture than the earlier 720 and 30 Express, the 721/722 was by several measures the company’s first successful bolt rifle. It was designed by Homer Young and Merle “Mike” Walker, who gave it a Spartan but pleasing profile. Walker, a Benchrest competitor, insisted on features that enhanced accuracy. The recoil lug was a thick steel washer sandwiched between receiver face and barrel shoulder. A clip-ring extractor, plunger ejector, and self-contained trigger group, with stamped-steel bottom metal, reined in cost without functional compromise. The twin-lug bolt head was brazed to the bolt body, as was the bolt handle. The receiver and barrel, and the perimeter of the recessed bolt face, surrounded the case head with “three rings of steel.” At the .222’s debut, Remington added it to the 722’s cartridge roster.

In the March ’48 issue of American Rifleman, Julian S. Hatcher declared the new Remington the strongest, safest bolt-action around. That year, you could buy a new 722 in the charter chamberings of .257 Roberts and .300 Savage for $74.95. “A” and “B” grade designations would change in 1955 to ADL and BDL. The Model 725, a 1958 upgrade, would feature a hinged floorplate and checkered walnut stock, a hooded front sight and adjustable rear. In December 1961, the 721, 722, and 725 would be supplanted by the glossier but mechanically very similar Model 700.

The Sako 46 bolt rifle, introduced in 1946 for the .22 Hornet and .218 Bee, was just the right size for Remington’s new round. Known then (and later through the ’50s and ’60s) as the Vixen, it added the .222 right away. Hunters applauded. I understand an L469 designation came to the L46 when modified to take the slightly longer .222 Magnum cartridge after its 1958 debut. In 1961, the L461 action replaced the L46. It would later be barreled to .223 and .17 Remington as well as to the .222 and .222 Magnum.

Meanwhile, Remington was finding other homes for the triple deuce. Its Model 760 pump rifle had replaced the 141 in 1952. Six years later the .222 was added to the 760’s big game chamberings, only to be ousted from that family in ’61. By then, Remington had unveiled its Model 40X Rangemaster target rifle. It chambered the .222, .222 Magnum, .308, and .30-06. The 40X would become the 40XB, a Custom Shop product, in 1964.

In mid-century, Savage was still leaning heavily on its lever-action Model 99 for revenue, a rifle ill-suited to a small target/varmint cartridge, and not easily adapted to it. But Savage’s 340 bolt-action had by coincidence appeared in 1950. Designed for the .22 Hornet and .30-30, it quickly snapped up the triple deuce. It would add the .222 Magnum and .223. I came late to a Savage 340 in .222 and had no idea how well it would shoot. In 1954 it had retailed for $48.75! The dim 3/4-inch scope screwed to the receiver did this specimen no favors, but it has shot as accurately as much more expensive rifles manufactured since.

In 1962, Remington unveiled its Model 700, essentially a refined 721/722. It had a swept bolt with a checkered knob and cast alloy (not stamped steel) bottom metal. The stock’s higher comb better suited scopes, though barrels still wore iron sights. Mike Walker cut the lock time to 3.2 milliseconds, reduced the leade and insisted on tight bore and chamber tolerances. The 700 came in two action lengths and two grades. The ADL with blind magazine and pressed point-pattern “checkering” listed for $114.95. A grip cap and forend tip, white-line spacers and fleur-de-lis panels distinguished the BDL, which cost $139.95. Magnum versions (7mm Remington and .264 Winchester to start) retailed for $15 more. The .222 was a charter offering. During the first two years of production, it was chambered in 20-inch barrels, as were the .222 Magnum, .243, .270, .280, .308, and .30-06. In 1964, M700 barrels for non-magnum rounds were standardized at 22 inches. Remington fitted magnums with 24-inch barrels. Variations would appear.

In 1956, the earliest ammo list that comes readily to hand, .222 cartridges by Remington, Peters, Winchester, and Western featured 50-grain softnose bullets and cost $2.40 per box. Remington also sold a “metal case” or FMJ load. Five years later, just before the 700’s debut, .222s were priced at $3.00 a box.

Introduction of the .222 Magnum in 1958 had little affect on demand for the .222. But the 1964 entry of the .223, loaded for service rifles as the 5.56 Ball Cartridge M193, bit deep into the .222 market. Remington’s collaboration with Springfield Arsenal had brought forth the Magnum, which drove 55-grain bullets about 100 fps faster than the .222 sent 50s. Developed with battle rifles in mind, it would give way to the.223. (The Magnum’s 1.85-inch case holds roughly 4 percent more powder than the 1.76-inch hull of the .223 but was deemed less suitable for Eugene Stoner’s Armalite rifle). The .223 has been available in many more rifles than has the triple deuce.

In my youth, many Benchrest shooters found the .222 their ticket to the top of the score-board. It all but ruled the circuit until the PPCs appeared in the 1970s. Hunters liked its efficient design, its mild report and its flat trajectory (7 inches of drop at 300 yards, with a 200-yard zero). Remington’s 700 and Sako’s Vixen were fetching rifles, and accurate.

The .222 appeared in some unlikely places as well. In the far north, economy-minded Inuits, who never used big bullets when small bullets sufficed, found well-directed .222 missiles adequate for caribou and seals. In Austria’s Alps, I shot my first chamois with a .222 borrowed from a local hunter who spoke no English. We sneaked within 130 yards of one of these wary goats. A 50-grain bullet through the front ribs sent it tumbling down the slope.

A cornucopia of .224 bullets makes the triple deuce more versatile than it was in the 1950s. New propellants give it more zip. Hornady’s Superformance load hurls a 50-grain V-Max bullet at 3,345 fps — faster than the standard starting velocity of a 55-grain spitzer from the .223! It’s still clocking 2,200 fps at 300 yards, where its 540 ft-lbs of energy matches that of a traditional 150-grain load from a .30-30. With bullets of 40, 50, 55, and 62 grains, Norma lists a suite of loads for the .222. Nosler and Hornady stoke 35-grain sptizers to 3,750 fps.

While fragile, lightweight bullets can reduce the likelihood of a pelt-shredding exit in coyotes, a solid or a softpoint designed for bigger animals can save fur in lighter game, where exits are the rule even with brittle bullets. Impact speed has much to do with the violence of tissue and fluid movement during penetration, so for many tasks the .222 trumps the .22-250 and its frothy kin. At 300 yards, there’s only 3 inches less drop from the .22-250. To 400, Remington’s 50-grain AccuTip BT bullet from the triple deuce traces about the same arc as a 165-grain AccuTip BT from a .30-06!

These three factory loads show what you can expect from a .222 across a range of bullet weights.

35-grain NTX (Hornady)

muzzle / 100 yds. / 200 yds. / 300 yds. / 400 yds.

- Velocity, fps: 3760 / 3148 / 2615 / 2140 / 1719

- Energy, ft-lbs: 1099 / 770 / 531 / 356 / 230

- Arc, inches: -1.5 / +1.0 / 0 / -6.2 / -20.1

50-grain AccuTip Boat-Tail (Remington)

muzzle / 100 yds. / 200 yds. / 300 yds. / 400 yds.

- Velocity, fps: 3140 / 2744 / 2380 / 2045 / 1740

- Energy, ft-lbs: 1094 / 836 / 629 / 464 / 336

- Arc, inches: -1.5 / +1.6 / 0 / -7.8 / -23.9

62-grain SP (Norma)

muzzle / 100 yds. / 200 yds. / 300 yds. / 400 yds.

- Velocity, fps: 2887 / 2464 / 2078 / 1731 / 1420

- Energy, ft-lbs: 1148 / 836 / 595 / 413 / 262

- Arc, inches: -1.5 / +1.9 / 0 / -10.3 / -35.5

Standard 1-in-14 rifling twist in .222 rifles excels for bullet weights to 53 grains. The Norma load and long bullets of 55 grains and heavier may require faster spin.

Handloaders have found the .222 well served by several medium-fast powders. BL-C2 and IMR 4198 are champs, yielding snug groups at near-maximum speeds.

Now past Medicare age, the .222 is even friskier than it was during the Truman administration. It still ranks among the most inherently accurate .22s. A mild report and negligible recoil make it fun to fire in lightweight “walking” varmint rifles. It has more reach than you’ll need for called predators, and sends bullets flat enough for point-blank aim as far as you can easily hold on a prairie dog.

The triple deuce ages well. A more companionable .22 centerfire is hard to name!