They languished for most of a century. What’s so special about Remington’s newest .35 — the .360 Buckhammer?

by Wayne van Zwoll

In 1906, a modified .30 for the 1903 Springfield rifle snared headlines. The .30-03 was conceived in 1900, when Springfield Armory engineers began work on an infantry rifle to replace the Krag-Jorgensen, just home from the Spanish-American War. A prototype cartridge in 1901 sent a 220-grain bullet at 2,300 fps — a ballistic match for Germany’s 8×57 with a 236-grain bullet at 2,125 fps. Then in 1904, Germany switched to a 154-grain “spitzer” bullet at 2,800 fps. The U.S. responded with the “Ball Cartridge, Caliber .30, Model 1906.” Its 150-grain pointed bullet, which clocked 2,700 fps, had a long ogive (forward taper) that prompted the Army to trim the case .07, to 2.494. All .30-03 rifles were recalled for re-chambering.

This military one-upmanship got little attention from hunters stateside. They were still starry-eyed over the smokeless powder fueling the rimmed .30-40 Krag and lever-rifle cartridges of the 1890s, like the .30 W.C.F. (.30-30) and .303 Savage.

But news in 1906 also included release of a quartet of rimless Remington hunting rounds for its just-released Model 8 autoloading rifle. All — the .25, .30, .32, and .35 Remington — would be offered, too, in the Model 14 slide-action of 1912, then in the improved Models 81 and 141, and in Remington’s bolt-action Model 30. The .25 and .32 were first to give way to more popular options. The .30 outlived them but faded in the 1940s. The .35 hung on, thanks largely to Marlin’s 336 lever rifle, trotted out in ’48. Soon thereafter, Remington announced new Models 760 and 740 slide-action and autoloading rifles. They fired longer, peppier cartridges, including the .30-06 — though the first 760s were also sold in .35 Remington.

This .35 certainly wasn’t the first! The Maynard rifle of 1865 was chambered the .35-30 Maynard — arguably not quite a cartridge. Its metallic case had a central flash-hole, but the primer was a traditional external cap. It evolved into the self-contained .35-30 and .35-40 Maynards of 1882. Now, over 140 years later, we have a cartridge that looks much like the .35-40! Oddly enough, the .35-40’s bullet diameter is in the new .360 Remington Buckhammer’s name.

Yes, the Buckhammer has more authority. Its 200-grain .358 bullet clocks 2,217 fps and carries over a ton of energy out the muzzle — twice that of a .35-40 factory load. With 180-grain bullets at 2,399 fps, the .360 has a velocity edge of about 300 fps on Winchester’s .350 Legend.

Like the Legend, Remington’s Buckhammer is targeted to the “straight case” market. Michigan and Ohio are among a handful of states that now permit deer hunters to use some rifle cartridges without bottleneck cases in traditional shotgun-only areas. Joel Hodgdon, Marketing Director at the Remington ammunition factory in Lonoke, Arkansas explained: “We designed the .360 Buckhammer to pass muster as regards case shape, length, and diameter so it could be used in these areas. But even where rifles have always been carried, we wanted the .360 to challenge other popular deer cartridges.”

With the profile of a silo and the moniker Remington once used on a shotgun slug, the .360 could easily be dismissed as a short-range “woods” cartridge, and relegated to ignominy with ranks of .35s since the .35 Winchester (in 1903, a fine deer and elk round for Winchester’s 1895 rifle). Many deserved better. Of those that didn’t, not all were hunting cartridges. In 1905, the .35 Winchester Self-Loading for the T.C. Johnson-designed Model ’05 rifle sent 180-grain bullets at 1,450 fps. Winchester dropped it in 1920 and replaced it with the .351 WSL in Johnson’s improved Model 1907. Bullets left 400 fps faster, but hunters had little to cheer. Both rounds used .351-diameter bullets; both saw service mainly in police rifles.

Charles Newton’s .35, a 1915 cartridge with the punch of Winchester’s much later .338 Magnum, was one of several worthy hunting rounds that should have gained more traction. Others: the .35 Whelen (adopted by Remington in 1987), the .358 and .356 Winchester, and the .350 Remington and .358 Norma Magnums. Since Winchester introduced the .270 in 1925, the trend in cartridge development has favored fast, flat-flying bullets. No matter that most game is still shot inside 200 yards!

But now, experienced hunters are shyly giving the .360 Buckhammer fond glances.

Announced at the 2023 SHOT show, it took a couple of years to develop. The working name was the .358 Buckmaster — a nod to the project’s chief engineer, Rick Buckmaster (honest!). The .360 has the .30-30’s case, necked up and shortened from 2.040 to 1.800 inches. Why didn’t Remington use the 1.920-inch hull of its .35 Remington? The .35 has a “fatter” case (base diameter .457 compared to the .30-30’s .419). Making a ‘straight’ case of the .35 Remington would have been a challenge.

Ballistically, the .360 upstages its parent, with a 180-grain Core-Lokt leaving the muzzle almost 200 fps faster than a 170-grain from a standard .30-30 load. While the .30-30 bullet has greater sectional density and catches the .360’s after 150 yards or so, the .360’s weight advantage remains.

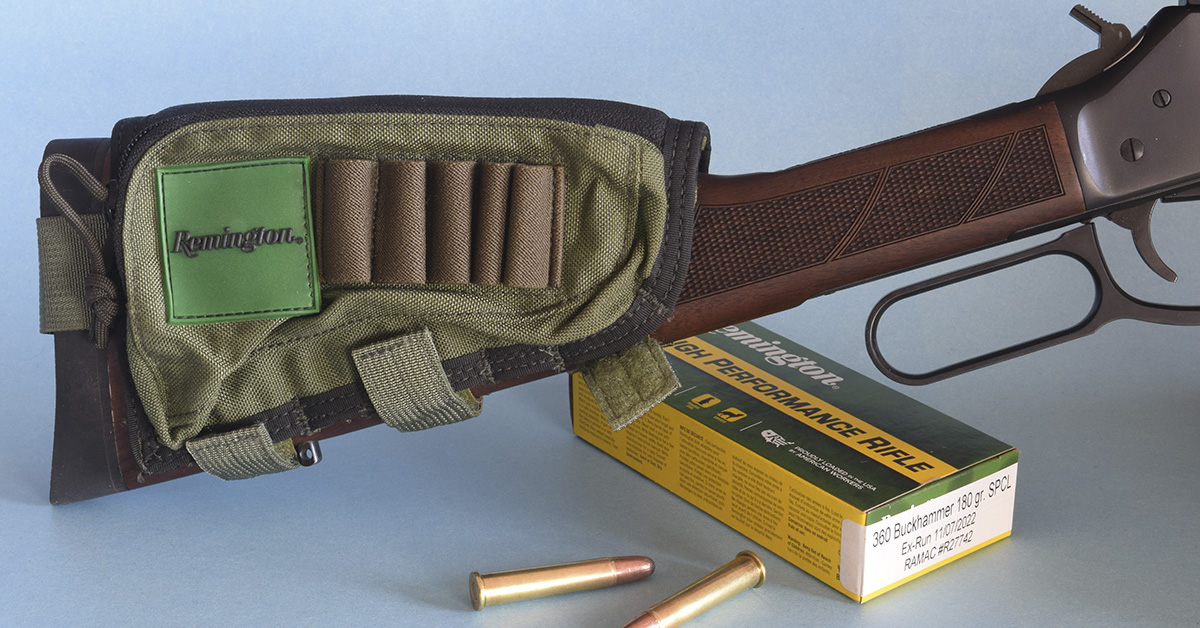

Henry was the first manufacturer with a rifle in .360 Buckhammer. Other rifle-makers are surely eying this cartridge — Ruger for Marlins. A Henry identified as a prototype came my way, on loan. “We anticipate tweaks in rifling twist and chamber dimensions,” cautioned Joel Hodgdon. “Accuracy should improve with later rifles.”

Unsurprisingly, Henrys in .360 look and handle just like the company’s .30-30s. My sample had a straight grip and standard (tight-for-big-hands) lever. Henry also lists rifles with a comfortably long pistol grip, an over-size lever. I can’t say if either, or the case-colored receiver or octagon barrel optional on .30-30s and .45-70s, will be offered on .360s. Henry does plan to chamber the cartridge in its X Model, whose synthetic stock has M-Lok slots and a Pic rail up front. The X barrel is threaded 5/8×24.

On the sample rifle, a Velcroed cheek pad aligned my eye with a 3-9x Bushnell scope. The crisp, 3 ¾-pound trigger helped me break shots where I wanted to hit. No tugging, no rough trigger travel. My first groups were neither bad nor inspiring — about what I once expected of lever-action deer rifles. Three 180-grain Core-Lokts that landed inside 1 ¼ inches suggested this cartridge in improved bores will deliver fine accuracy.

Feeding and ejection were smooth and reliable. The Henry’s hammer has no half-cock position, no cross-bolt safety. A transfer bar helps prevent accidental discharge. I used the side loading gate only to test its function, preferring to drop cartridges into the magazine up front, as with a tube-fed .22. Easier on my thumb! More makers of lever rifles should offer that option!

Free recoil of the .360 in a 7 ½-pound rifle averages 14 ft-lbs., roughly 30 percent more than from a .30-30 rifle of that weight, and 30 percent less than from a .270. Neither the Henry’s kick nor the blast from its 20-inch barrel was punishing. A thick, black butt-pad spared me the sting of a steel plate; the 14-inch pull of the walnut stock kept the scope from dinging my brow.

In sum, I think the .360 a fine fit for traditional lever-action carbines. Its stocky profile makes for efficient powder burn in short barrels. With traditional bullets, it hits harder than the .30-30 and shoots as flat. With Remington’s 200-grain Core-Lokts, I’d use it elk hunting, too!

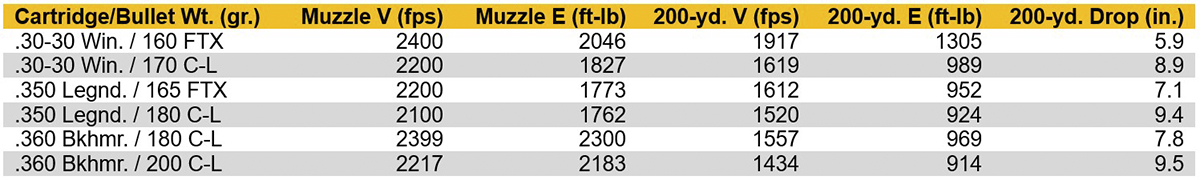

Ballistics at a Glance

Remington calls the .360 Buckhammer a 200-yard cartridge. Both 180- and 200-grain Core-Lokts bring over 900 ft-lbs that far. The 200-grain Core-Lokt is 18 percent heavier than a .30-30’s 170. It has 16 percent more frontal area — a factor in killing effect that’s largely ignored by hunters seduced by fps and ft-lbs. While hunters with pie-eyed optics and long-nosed bullets focus on the blue yonder, deer drop by the many thousands to cartridges like the .360. No bipods or rangefinders needed!

[Ballistic performance of factory loads for the .30-30, .350 Legend and.360 Buckhammer (100-yard zero)]

Note: Remington Core-Lokt (C-L) bullets are traditional softpoints. FTX bullets, in Hornady loads, have pointed, soft-polymer tips. Both are safe to use in tube magazines.

Diameter Details, and…

Bullets for the .360 Buckhammer and .350 Legend are not interchangeable. While the .360s are of .358 diameter, standard for 35-caliber rifle bullets for over a century, SAAMI’s spec for .350 Legend bullets is .355. “In production, that number is .357,” says Winchester’s Nathan Robinson. “There’s -.003 tolerance, per .357 Magnum bullets. Groove diameter in .350 Legend barrels is .355.” Pistol bullets aren’t used in .350 Legend factory ammunition, as they’re not designed to kill big game at high (rifle) velocities. The Legend’s 180-grain Power-Point is 22 grains heavier than .357 Magnum hunting bullets.

It’s worth noting that the .360 Buckhammer, ballistically the .350 Legend’s superior, is not suited to AR mechanisms. The Legend is.

Neither Gone nor Forgotten!

While the .35 Remington is a bigger cartridge than the .360, traditional loads don’t hit as hard as do factory-loaded .360s. SAAMI breech pressure for the .35 is 33,500 psi, frothy in 1906 but modest now. Rifles and powders have advanced considerably over the last century; still, loads for old cartridges must match early steels, mechanisms, and cases. The .35 Remington has been blessed with positive changes. A 150-grain load died, mercifully, when hunters found the slower 200-grain Core-Lokts better battled drag, stayed on course more reliably in cover, and drove deeper in big bucks. Hornady’s 200-grain FTX bullets fly 10 percent faster than 200s in traditional loads. Federal’s new 220-grain HammerDown load strikes me as a most promising option for the aged but able .35 Remington!