Our author has examined hundreds of shooting incident reports over the last half-century, and there are some common denominators you need to know to protect yourself

by Bob Campbell

I have studied personal defense for more than fifty years. Human conflict is no stranger in my life. I grew up in an area no more violent than any other. I would imagine, less so than some. But violence is far from an abstract concept.

As an example, I recently had a small finding of basal skin cancer, which was deftly handled by a man wielding much knowledge and a scalpel. The findings, though, necessitated a full body scan. If you have not had the pleasure of such a scan — the epidermis is the body’s largest organ and demands respect — the process is used to catalog scars. Some may be the beginning of skin cancer, which, thank God, only a couple of mine were. I think the final count was more than fifty scars, including quite a few on the knuckles, a couple of edged weapon scars, and one healed bullet pucker. The worst jig-jag scar was the result of a compound fracture on an appendage I have broken twice. Looks like a big zipper. Doctor W. commented they did “imaginative work” back in the day. The good doctor was curious, and I simply commented that I had been a peace officer. Fell off a horse. Got on the bad side of an angry dog. His medical knowledge indicated no worries as the Scotch-Irish seem born with a broken nose and scars on their knuckles. I had to agree.

Back to my specialty.

My findings here are generalized as there is no set pattern for gunfights. My friend Miriam and I agree on a big change in human conflict that has come about over the past thirty years. We have known each other for decades and worked at the same church. My background is criminal justice and psychology while she worked as a psychologist for thirty years, including working with the DSS in our state. While we use different terms, the single biggest change we notice is the reason people commit violence.

When I first became involved in police work, crimes were committed for a reason. Most often a stupid reason, but there was a reason. Folks did not risk many years in prison on a whim. Today, there is less of a reason for violence and violence is perpetrated for its own sake. While this was sometimes true in the past, gratuitous violence did not exist in the wholesale pattern it exists today.

We are not folks who miss our previous occupations, although I do keep my hand in. I am very interested in training and train and study on a daily basis. For many folks, the worst foreseeable incident is a minor bump up or perhaps a financial theft. Yet death and crippling injury lay in wait for the unprepared. A gunfight may come at you like a car wreck or you may have a few seconds warning.

A gunfight is a series of events. I have secured quite a few case histories of gunfights from a mix of police and citizenry. Some are from case studies I was allowed to view, and some were leaked from official files. A leak is OK, depending on whose hand is on the tap and in this case, a good purpose has been served. Statistics are used for the most part by rascals to impress fools, according to the late and much respected Colonel Cooper. He saw through the so-called stopping power studies for what they were. Quackery at best. Secret sources and non-repeatable, non-verifiable research are worthy of being called a hoax. Load performance is measured in the laboratory where results are repeatable and verifiable. Tactics and marksmanship are areas that may be studied if sufficient background is available. When applied to training, one conclusion from reputable study is that greater training and more repetition should lead to better marksmanship and more hits in defensive situations. You would think, and as it happens, agencies that qualify two to four times a year have better shooters than those that don’t.

An agency with very good after-action reports is the NYCPD. It is easy to pick on them as a result, but don’t. They do their best with what they have. Hopefully you have more time to practice and get to the range more than once a year. It is difficult to rate the effectiveness of certain handgun cartridges as the person shot may be ‘doped up’ or may not be and the bullet may impact anywhere on the body. Safe to say larger calibers make a bigger hole and let out more blood. But the tactics used seem more important given a caliber of at least 9mm or .38 Special. In about 150 shootings, the hit rate, as far as I am able to determine, is about 35 percent. Some agencies have a 52 percent hit rate.

Close study shows that in about half of police shootings, the officer eventually hits the assailant. On the other hand, the most accurate shooter — the man or woman who gets a hit first — often fires a single shot and stops the fight. Is it training or luck? Probably a bit of both and a liberal dose of mindset and nerve control. We want to be the person who survives and who fires a minimum of shots. After all, a flurry of shots doesn’t seem to help. I don’t know who coined the term “spray and pray” but it certainly fits some shootings. Let’s understand the problem in depth and add that to our knowledge. The bottom line is that if we escape serious injury, the outcome is praiseworthy.

On the civilian side within a week, there was a road rage incident, where an aggressor fired fifteen rounds without a hit on a person. The defender fired two shots that missed but scared the aggressor off the road. In a gang-related shooting that week, the local Sheriff’s office reported 116 shots fired for one hit. Neither side hit their rivals, but an innocent woman was struck once and killed.

A Sheriff’s department I was allowed to study logged 27 incidents with one shot fired and a single hit recorded in each incident with a high degree of incapacitation using 9mm +P+ loads. They recently logged an incident with five shots fired and two hits. In that case, the felon was armed with a rifle and the two hits by the deputies were taken at about 23 yards.

This department has had a long line of excellent instructors and dedicated Sheriffs. So, while hit probability is all across the board in my study, and obviously the problem may be addressed, in this department, it has been addressed successfully.

Preparation and training are necessary. Mindset alone isn’t enough. The adversary usually combines the two most undesirable human traits of mean and stupid. Reasoning with this type of human being is difficult…and so is the fight. Training that gives you plenty of time to shoot and draw isn’t always the best choice. Reaction time is a constant that isn’t easily improved. Your synapses are only so fast, but you may condition your reflexes and movements to be as fast as possible. And you may condition your mind to work more quickly. Being aware and present in the moment is the single most important step.

Realistic scenarios are important. It is acceptable to begin training from the seven-yard line and firing at a stationary target you are facing. This type of drill is easily squared away but it isn’t much of a preparation. The drill has two dimensions: you react to a self-starting stimulus or the outside stimulus of a whistle or command.

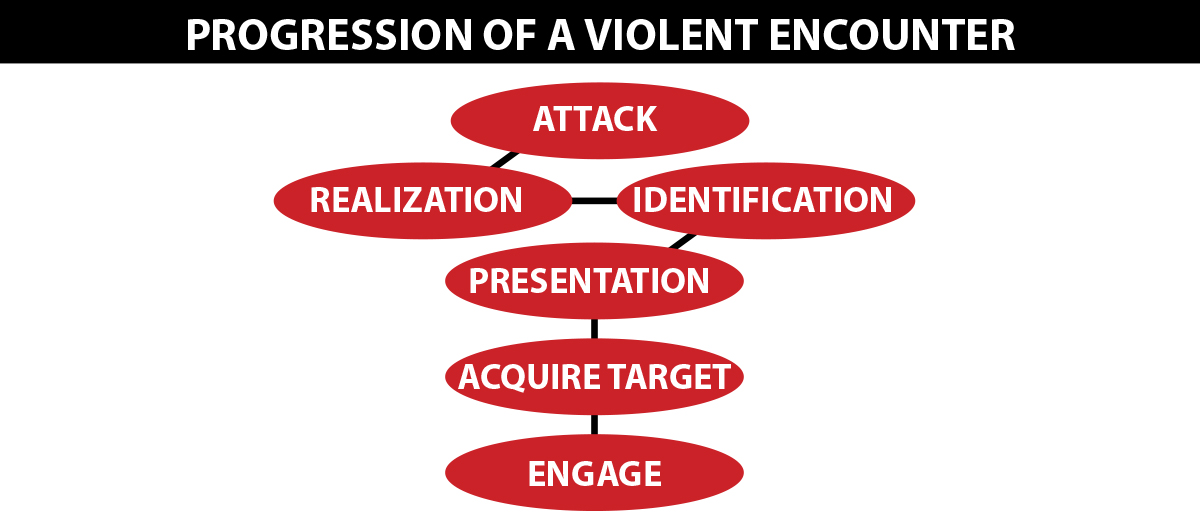

Here are the steps that I have isolated in a defensive encounter. I have considerable experience in studying, creating, and teaching emergency flow sheets. This outline is similar in concept. Every incident does not lead to a fight and every incident isn’t the same, but certain principles follow.

Attack

When you come under attack, there is a reaction. It may be to raise your arms over your head to fend off a blow, depending on the distance at which the attack begins. Or it may require you draw your weapon and fire.

The attack may be non-lethal and demand a kick, a left hook, an uppercut, or application of pepper gas. The response isn’t always lethal and must not be over the top but reasonable. As you debate how much force is reasonable, you also save yourself from significant injury or death. Simple, isn’t it?

Realization

Realizing you are under attack is important. A second spent in disbelief is common, so get going and react. A good reaction that fits some scenarios is “feet don’t fail me now,” and that may be all that is required.

Responding to a gun or an edged weapon requires a violent response on your part. You may be facing someone who has chosen you as a victim of opportunity or you may be the object of an ambush predator. Either way, you must react with a clear head.

Realizing you are being assaulted or threatened may come at the moment of the attack, or you may realize the attack is coming before it actually is in progress. So, the first two parts of the diagram are flexible.

Be aware of things seen out of the corner of your eye. A shoulder dropped or a balled fist coming at you may be the warning. The attack may not be personal, as in a stick-up robbery. The attack may be directed at a group of people, even a crowd or a congregation. Whatever the attack, you must realize the attack is in progress. Often, the attack is so senseless you are surprised there is no objective reason for it. Don’t let that surprise slow your response.

On another front, if you hear the breaking of glass, a door struck open, or the dog whelping, you will realize the home is being invaded. If you are sleeping, the lag in reaction time may be deadly.

In one well-documented incident, a homeowner rushed to aid his wife as the front door was the focus of a home invasion. The homeowner forgot to access two loaded handguns in his bedroom. While the couple survived, each was hurt — the wife getting the worse end of the deal.

Identification

In a street or robbery situation, identification is less difficult. The fellow in front of you with a shiv has targeted you. In a home defense situation, identification is critical. There are worse things than being shot, and shooting the wrong person is one of them.

There are many incidents in which family members or neighbors have been shot by mistake — and responding police officers have shot homeowners. Some are tragic accidents while others are criminal. Such situations would seem unbearable to most of us and should be avoided. Common sense training and target identification will avoid these tragedies.

Another question in identification may involve an active shooter. You may have difficulty finding the source of the bullets cutting into the crowd. It is also important to identify a threat instead of an armed citizen responding to a threat. I could probably pen an article on target identification (and maybe I will!). It is a more complex subject than it first appears, so study this problem with all of the time it deserves.

Presentation

An attack is in progress and you have identified the threat. The next step is to present the handgun from concealed carry. In a conventional draw from a strong side holster, the elbow shoots to the rear and the hand comes up from below the handgun to scoop the handgun from the holster. The handgun is pushed toward the threat and aimed properly. Sight acquisition and marksmanship are not part of this report, but be certain to realize that the presentation leads into the firing stance and marksmanship. A crossdraw appendix carry or pocket carry demand their own drills.

Acquire the Target

The time has come to act. The handgun is presented from concealed carry. The presentation leads to the firing stance. The handgun’s sights are superimposed over the target. It is important that we use our sights save at very close range — three yards or so. The sights are quickly aligned and the front sight is the primary focus. Instinctive shooting or point shooting is as useful as driving with your eyes closed. Think about this. In a shooting in which the defender missed the threat and struck an innocent person, would you wish to be the instructor who taught the shooter not to use his sights? Of course not. Always aim the pistol.

Engage the Threat

Up to this point you may stop the action if the threat retreats or suspends their deadly action. At the point when the target is engaged, the trigger finger is finally on the trigger and not before. The sights are lined on the target, the target has been acquired, and the target is engaged with fire. That is to say, a threat is engaged with accurate fire. Area aiming, shooting for the entire target, isn’t used. You aim for a small part of the target/threat. The bullet is directed where it will do the most damage and create a cessation of the threat to your life.

The shooting may take place in the matter of a few seconds. If you see the attack coming, a rapid response may stop the fight before it begins. Use this diagram to help you understand the progression of a violent encounter and to either prevent it (best scenario) or to eliminate it.