The metallic cartridge, not the repeating rifle, gave soldiers and hunters a second chance!

by Wayne van Zwoll

The Director of Civilian Marksmanship once offered 1873 Springfield rifles to NRA members for $1.25 apiece, plus shipping. It seemed a dismissive farewell to the U.S. Army’s first cartridge rifle. The “Trapdoor” Springfield, so called for a breech-block that swung up for loading, was “The Gun That Won the West” in William Castle’s 1955 film of that name, with Dennis Morgan, Paula Raymond, and Richard Denning. Arguably, it merits that title despite attempts of lever-action Winchesters to kidnap it.

By the end of the Civil War, the 1860 Henry had impressed troops and President Lincoln. Despite its anemic .44 ammunition, it showed the future of combat arms lay in repeating cartridge rifles. The .58-caliber 1865 muzzleloader issued to Union troops was on its way out, so Erskine S. Allin, head mechanic at Springfield Armory, designed a breech-loading conversion for it. His hinged breech-block, fitted to the milled-out roof of the chamber, held the firing pin. Drawing the hammer to half-cock let the breech-block spring open. Late in that arc, it activated the extractor, which kicked the spent case over an ejector stud. Barrels on muzzle-loading Springfields were reamed to .64 caliber, then sleeved and fitted with the Allin breech and chambered to the centerfire .50-70 Musket cartridge. Each conversion required 56 machining operations and cost the Army $5. In 1872, the Ordnance Board approved Allin’s work — with a separate receiver and a threaded .45-70 barrel.

The 1873 Springfield fired .50/70, then .45-70 cartridges, each keeping breech pressures around 25,000 psi. In infantry rifles, the 405-grain .458 lead bullet at 1,320 fps was later shelved for a 500-grain bullet with longer reach. For carbine use on horseback, the 405-grain bullet was seated atop wads and a 55-grain powder charge to reduce recoil. The Springfield’s fast-opening breech helped the Army prevail in its battles with Indians — at least until tribes acquired Henrys and Winchester 1866 repeaters. On June 25, 1876, above Montana’s Little Bighorn River, General George A. Custer’s troops died using Springfields.

Officially replaced in U.S. arsenals by the Krag-Jorgensen bolt rifle in 1892, the ’73 Springfield armed state militias for many years thereafter. During the Spanish-American War, all volunteer regiments besides Theodore Roosevelt’s Rough Riders carried trapdoor Springfields. Minnesota’s National Guard still had nearly 1,000 when Hitler invaded Poland!

Certainly, the most famous Springfield of that time is “Lucretia Borgia,” the .50-70 rifle William F. Cody named after a femme fatale in an Italian opera. He acquired it in 1867 and favored it for most of his career hunting buffalo for the Army. “Buffalo Bill, Buffalo Bill. Never missed and never will. Always aims and shoots to kill. And the company pays his buffalo bill!” Attributed to rail crews also fed by his able horsemanship and deadly aim, that ditty may have produced the nickname Cody was pleased to own, on the prairie and later as the star of his Wild West Show.

Naturally, other hunters took note of his celebrity. One was Michigan native Billy Comstock. Born in 1842, he was four years older than Cody. He followed a similar career path, riding for the Pony Express after moving west, then working as a civilian scout for the Army and hunting for the railroads. At Fort Wallace, Kansas, Comstock impressed Army officers with his marksmanship. In the summer of 1868, he and Cody agreed to a buffalo-killing match. Sponsored by the Kansas-Pacific Railway, the hunt would occur in Logan County, Kansas, east of Fort Sheridan, where there were lots of buffalo.

“We were to hunt one day of eight hours,” Cody later recalled. The purse of $500 a side went to the man “who should kill the greater number of buffaloes.” Cody claimed he had an edge on Comstock. insisting his mount Brigham was “the best buffalo horse that ever made a track” and that his Springfield, “known at the time as the needle-gun,” was a better rifle. While he conceded Comstock’s Henry “could fire a few shots quicker,” Cody was convinced “it did not carry powder and lead enough to do execution equal to my caliber .50.”

Predictably, bets from soldiers on the hunt’s outcome favored the hunter who supplied meat to their post. Fort Hays troops cheered Cody; Fort Wallace had money on Comstock.

When the hunt began, the contestants’ tactics proved as different as their rifles. Cody galloped to the front of herds to kill the lead animals, piling up others trying to dodge mounting carcasses and forcing the remainder to run in circles. It was an efficient method, yielding easy targets that could be shot in quick succession, with less riding than required of Comstock, who chased the buffalo, firing as he caught them. After eight hours, Comstock had 46 kills strung over three miles of prairie. Cody tallied 69 in clusters.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the world, Great Britain was arming soldiers in its colonies with Martini-Henry dropping-block rifles in .577/450. Adopted in 1871, this cartridge was based on the .577 Snider cartridge of 1867, necked to accept a 480-grain .455 bullet. (While U.S. habit is to name the bullet diameter first, the parent case second, the Brits reverse that order in cartridge designations. The .45-70, of course, follows the 19th-century American tradition of pairing bullet diameter with black powder charge).

The bottleneck .577/450 differs greatly in profile from the .45-70, but ballistically they’re very close.

In many ways, the pivotal battle of the Zulu War of 1879 in southern Africa mirrors Custer’s final clash with the Sioux and Cheyenne. Both were fought by troops armed with a single-shot .45-caliber breech-loading rifles. In each, native warriors delivered a crushing defeat to a professional, uniformed army with modern arms and plenty of ammunition. At the same time, each was a pyrrhic victory, the last indigenous triumph against the inexorable force of organized military might and impending waves of settlers.

Even the failures are similar. Custer attacked a village without permission and without assessing its strength. Misjudging both the number and probable reaction of the fighting men, he split his command. In the Cape Colony on the Natal border with the Zulu kingdom, British officer Lord Chelmsford was not authorized to engage the Zulus in battle. His expeditionary force camped at the base of Mount Isandlwana on January 20. Confident in the strength of his 4,000-man column, he did not prepare defenses. The next morning Chelmsford left with a force of 2,800 to probe Zulu territory. His detachment was far off when scouts from the camp at Isandlwana crested the lip of an immense defile. Its belly was black with 20,000 Zulu warriors. Resting for the day, this army was preparing to attack the British on the 22nd. Discovered, they boiled out of the canyon as the scouts raced toward camp. The ensuing battle raged most of the day. The British were overwhelmed; more than 850 soldiers died.

While Zulu dead numbered over 1,000, that army was largely intact. After mutilating their slain foes, they left with armloads of Martini rifles, 400,000 rounds of ammunition, and two field guns. At least 3,000 diverted to kill a detachment of British soldiers at Rorke’s Drift ten kilometers away on the Buffalo River. Once the trading post of Irish settler James Rorke, the building was currently a mission station of the Church of Sweden. Its walls offered some security; however, as few as 150 soldiers were garrisoned there when the tide of warriors, brandishing assegais, crashed against their defenses. Combat was close and fierce, piling corpses at the foot of the walls as night came. Burning roof-thatch fired the sky.

Donald Morris chronicled this battle in his book, “The Washing of the Spears.” By nightfall “the defenders were exhausted and their throats were parched; their heads ached and their ears rang… Most of the men had fired several hundred rounds through their scorching barrels, and the fouled pieces kicked brutally, lacerating trigger fingers and pounding shoulders…raw. [Hot barrels] glowed dully in the dark, cooking off rounds before the men could [aim].” Knives stabbed at the cases of thin rolled brass, stuck in chambers by the searing heat after extractors tore off their iron heads.

At dawn, the Zulus sifted off, leaving 370 bodies. The British counted 17 dead, with many injured. In 12 hours, their Martinis had fired more than 19,000 of the 20,000 cartridges stored at Rorke’s Drift.

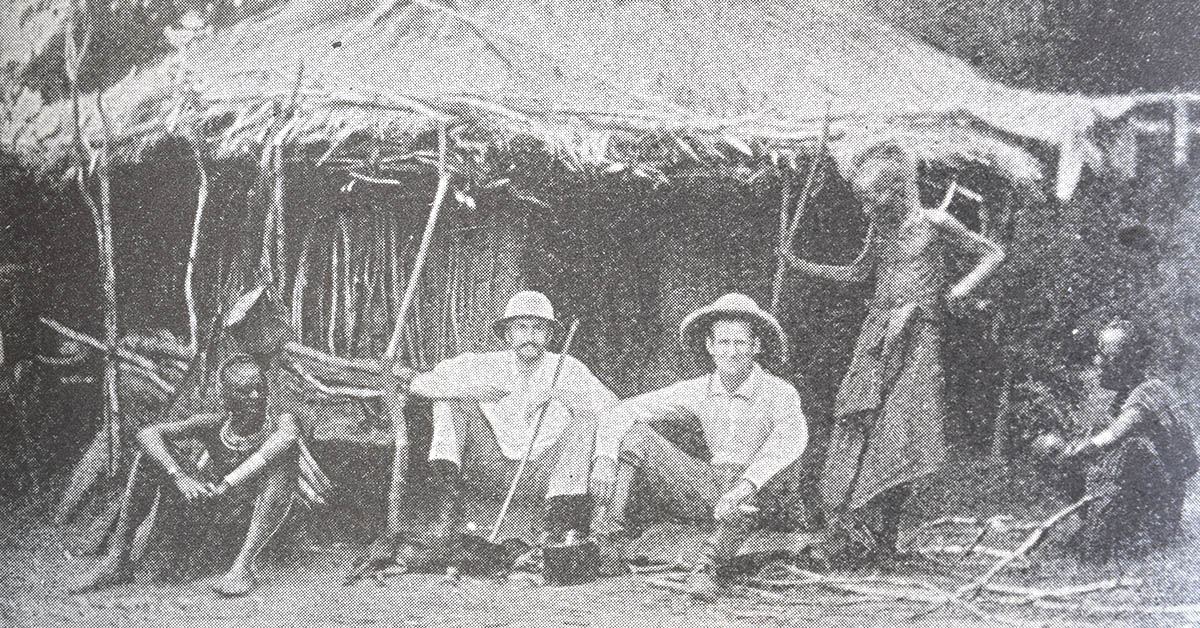

The .577/450 Martini also figured into J.H. Patterson’s quest in 1899 to kill two man-eating lions. whose depredations had stopped construction of the Uganda railway at the Tsavo River. The beasts were bold and almost unfailingly lethal as they prowled rail camps at night, snatching workers from tents and fires. With a Martini and a .303 SMLE, Patterson persisted, baiting and sitting in flimsy machans at night. After frustrating weeks, he found where one of the cats had killed a donkey. Only a hindquarter had been eaten. As lions “begin at the tail,” he secured the remains with a wire and sat.

Long after dark he heard a low growl. But the beast wasn’t after the donkey! Almost noiselessly it crept around Patterson’s perch, out of sight, edging closer. Two tense hours later, a feline form appeared at his feet. Patterson emptied the .303’s magazine as great roars burst from the bush. He did not descend until dawn. The 9-foot, 8-inch man-eater lay dead.

Night sounds on the veranda of a nearby bungalow put Patterson on lion spoor the next morning. He tied three goats to a 250-pound length of rail and sat. The cat ghosted in after dark, killed a goat, then dragged it, with the other two and the rail, into the night. Next morning, a tracking party found all goats dead but intact. Patterson threw together a machan and this time got shooting. The beast crumpled to twin shotgun blasts. But all optimism vanished when, the following day, blood sign and tracks disappeared in rocks.

Ten nights later, the lion came silently to camp, probing each tent, then circling a tree festooned with frightened coolies. Patterson’s wait the next night was short. At 20 steps he put a .303 bullet into the cat, rattling off three more as it dashed away.

Next morning, a growl brought the tracking party to an instant halt. Patterson spied the beast in a thicket. His shot brought it on. “I fired again and knocked him down; but in a second he was up,” When a third bullet took no effect, he reached for his Martini. It wasn’t there! Patterson vaulted into the nearest tree a jump ahead of the cat, joining his gunbearer. Two aimed bullets from the Martini dropped the man-eater. It measured 9 feet, 6 inches. It had been hit six times.

Between them, these fearsome animals — by appearances litter-mates — had killed and devoured at least 28 Indian coolies, along with uncounted African natives.

Colonel Patterson’s book, “The Man-Eaters of Tsavo,” was first published in 1907. A film based on it, Ghosts and the Darkness, starring Val Kilmer and Michael Douglas, was released in 1996.

While a full magazine brings comfort, a single-shot rifle urges careful shooting — and with proper incentive can be loaded very quickly!

The Springfield “Backstory”

The Springfield name, bestowed on U.S. military rifles from our first musket in 1795 through the era of bolt-action rifles, harks to Springfield Armory, ordered up by George Washington in 1777. Built at the confluence of the Connecticut and Westfield Rivers in Massachusetts, it first served as a repository for muskets and powder. Within 20 years it had grown to include a foundry and “water shops” hemming the Mill River dam that powered manufacturing tools. A century later it would produce the Krag-Jorgensen bolt-action, then the 1903 Springfield and, on the heels of the Depression, the self-loading Garand. In a 1968 budget decision, the Armory was shuttered. It became a National Historic Site in October 1974.