Luck has helped hunters take exceptional game. So have these rifles and loads.

by Wayne van Zwoll

The 1950s and early ’60s rewarded the generation blessed to have hunted in the Mountain West then. Lavonne had little field experience when she laced up her boots in the fall of 1961 and trudged into Wyoming’s hills. Her Springfield was pretty much as issued, a heavy rifle equipped only with issue sights — hardly an ideal pick for mule deer bucks, which might afford her only distant glimpses, if any at all.

But the antlers that caught her eye were not far off. And the .30-06 came up as if weightless. The blade shook as she tried to keep it on the deer. Lavonne pulled the trigger. At the blast and the blow from the Springfield’s butt, she fumbled for the bolt…

The animal she approached was as big as it had looked. It would later scale 357 pounds. The rack was a match, thick and with many points. Forty-one years later, it would earn a Boone and Crockett score of 269 inches! But Lavonne wasn’t thinking that far ahead. She was 12.

Steel tape tells nothing about a hunt. It measures only bone – tangible proof the animal lived and died. The circumstances of its last moments live in the memory of the hunter who shared them. You, for example. The shot may have come quickly, at first sighting, or after hours or days of effort — even seasons of seeking an outstanding specimen or that particular beast. You recall the place and your route that day. The weather, too, and choices that led to the hunt’s climax. The final moments are lucid: how the game came to eye, the approach, if any, and your shooting position. You remember the range and the sight picture, the animal’s reaction, perhaps the follow-up, even field dressing and pack-out. Remaining bone is but a token; what happened is what matters.

You probably recall the rifle and load, though they have no part in choosing when, where, what, and why you kill. And they’ve nothing to do with good fortune — even with the luck you make by honing your hunting and shooting kills, then persevering.

Records-book game is taken by all manner of rifles and loads, as it is by skilled hunters and raw recruits. But if no “book-class” animals live where you hunt when you’re afield there, you won’t kill one, regardless of your hardware or your talents. Taking note of rifles that have brought to earth exceptional game is, though, a harmless hobby.

There’s no magic in the cartridges that put scores and names on B&C lists. I’m just one of many hunters with an interest in such trivia.

Many big deer have fallen to Winchester’s John Browning-designed lever rifle introduced as the Model of 1894. It appeared initially in .32-40 and .38-55 — both black-powder cartridges. The smokeless .25-35 and .30-30 followed, in nickel-steel barrels. First hurling 160-grain bullets at 1,970 fps, the .30-30 later added muscle with 170s at 2,200.

One day in 1941, Jack Autrey tossed his Model 94 into his 1935 Plymouth and drove into the hills near his Colorado home. A short hike brought him up a ridge, where he spotted movement behind a bush. Then the bush moved! It was a huge set of antlers. Two bullets from Jack’s .25-35 killed the deer. Its rack had 32 points and, with a score topping 297 inches, ranks high on B&C’s list of non-typical mule deer.

The slab-sided, scabbard-friendly 94 carbine held its appeal in Colorado mule deer country. One morning in 1972, Mike Blehm and a pal saddled up to hunt in the Soapstone Hills. When a tall-tined buck appeared, Mike slid off his horse and yanked his .30-30 free. His bullet dropped the animal at 125 yards. Blehm figured it weighed 300 pounds. Its typical antlers later taped 195 inches. Another B&C entry!

Winchester’s New Haven plant shuttered in 2006; and after 112 years and over six million rifles, the Model 94 was discontinued. Revived, it remains the best-selling lever rifle ever.

The .30-30 and, beginning in 1902, the .32 Special grew ever more popular with deer hunters. In eastern whitetail woods, Winchester’s 1894 and Marlin’s 1893 lever-action carbines pointed naturally and delivered quick repeat shots. The .32 Special’s 170-grain .321 missile was a ballistic twin to the .30-30’s same-weight bullet, but the .32’s bore had black-powder roots, and some hunters favored the .32 Special. Ed Broder did.

On November 25, 1926, he and two friends gathered up rifles and camp gear and herded a 1914 Model T from Edmonton toward their cabin at Chip Lake, Alberta. When conditions got tough for the Ford, they stopped at a saw-camp to hire a team of horses and a sleigh to finish the 100-mile trip in a foot of snow. Upon their late-afternoon arrival, Broder immediately grabbed his rifle and tramped into the woods. Outsize tracks led him a half-mile to a fresh bed, then into a jackpine swamp. When he came upon the equally recent trail of two moose, he had a choice. The moose would almost surely take longer to reel in, and little of the day remained. So, Ed stayed with the original prints. As light drained from the sky, he came upon a clearing. There stood the buck, facing away. Patiently, he waited until the animal raised its head. At the snow-muffled pop of his .32 Special, the deer wilted. Walking up to it must have left Broder slack-jawed. Nearly a century later, its antlers remain the world record for non-typical mule deer, with a B&C score exceeding 355!

Not that lever-actions accounted for all records-book mule deer collected between the mid-1920s and the mid-’70s. The .30-06 was wildly popular in 03A3 Springfields, sold by mail-order houses for as little as $30 into the 1960s — but also in Winchester’s Model 70 and Remington’s 721. Both these rifles chambered the .270, too. Less well-known was the .257 Roberts, a wildcat adopted by Remington in 1934 and offered in its Model 30S bolt rifle, then in the short-action 722. In 1937 Winchester listed the .257 as a charter chambering in its Model 70.

The Roberts’ mild recoil made it popular with women like JoReva Beane Wellborn. In 1949, she took advantage of its bullet’s flat arc to down a Colorado mule deer at 200 yards. The typical rack spans 31 inches and scores a whisker shy of 195 on B&C charts.

Three years later, Winchester announced its .308, a cartridge even better suited than the Roberts to short actions. Stiff loads with heavy bullets gave it plenty of punch for elk. But Phyllis Crookston had big deer in mind when she took her .308 hunting during the 1961 season in San Juan County, Utah. The buck she met at 50 yards would have given pause to most hunters. But Phyllis wasted no time. Her bullet felled the animal, whose typical four-point antlers would tape over 199 inches!

Leupold’s development of a fog-proof Plainsman rifle-scope in the late ’40s would accelerate the trend to optical sights. But a decade earlier, as Europe inched toward war, most hunters still used metallic sights and cartridges developed before women had the right to vote.

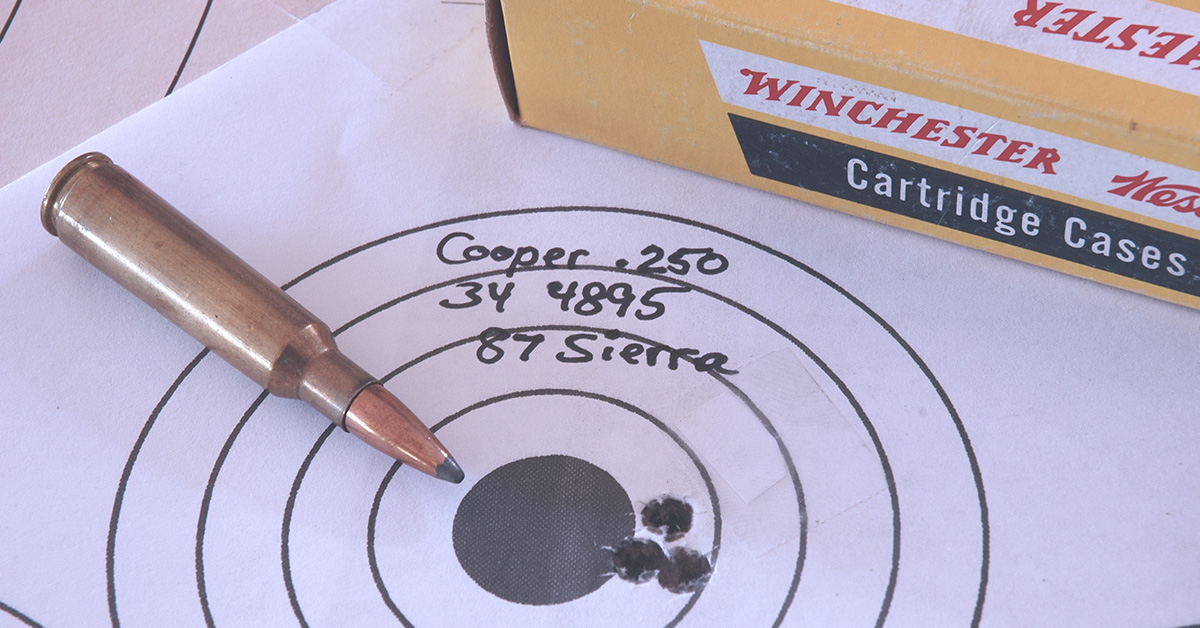

In 1920, the .300 Savage gave lever-action buffs flatter bullet flight and harder hits than the .30-30’s, in a hammerless rifle with side ejection. The Savage Model 99 rifle also had a spool magazine that allowed use of pointed bullets. Bill Goosman’s 99 was barreled to the smaller .250 cartridge released in 1913 by Charles Newton. Its 87-grain bullet left the muzzle at 3,000 fps — a rocket in that day, if not a top pick in elk cover. But it had earned Goosman’s confidence even for those big animals. In the fall of 1939, prowling timber in Colorado’s Beaver Flattops, he caught elk-scent and eased toward it. Glimpsing the bull at 45 yards, Bill took aim through his aperture sight. The beast collapsed to his shot. Its non-typical 400-inch antlers easily exceeded B&C’s minimum for that category, added in the 1980s.

While the 1950s and early ’60s drew many elk hunters to short-belted magnums, “old-timers” like the .250-3000 endured. The 6.5×55, a military cartridge from the 1890s, gave bolt-rifle enthusiasts modest recoil in Swedish Mauser carbines that handled like lever-action saddle guns. Melvin Van Lewen found its 140- and 160-grain bullets lethal on durable game. Early one morning in Colorado’s 1961 elk season, Van Lewen came upon big tracks in fresh snow. He followed them through intermittent flurries well into the afternoon. His persistence paid when he glimpsed his quarry through the trees 85 yards ahead. At the Mauser’s crack, the heavy six-point crashed away downhill, but tumbled a few yards on. Melvin retrieved the meat with a toboggan, three trips netting 502 pounds of venison. The rack taped over 376 inches!

The rifle John Plute used in 1899 to kill an elk whose antlers would top records lists for most of a century was almost surely a lever-action ’95 Winchester, the only rifle in photos I’ve seen of the itinerant Slovenian miner. The cartridge of record was the .30-40 Krag, which, in 1892, led the march to smokeless ammunition stateside. Other arms bored for it then included the U.S. Army’s Krag-Jorgensen bolt-action and Winchester’s 1885 single-shot. Less common: the Remington-Lee and Rolling Block in .30-40.

Plute probably used factory-loaded 180- or 220-grain softnose bullets in his open-sighted rifle. As the story goes, he downed the bull in Colorado’s Anthracite Creek, returning to Crested Butte without the antlers. He lived in a boarding house there and supplied venison to the Elk Saloon. When onlookers didn’t buy his description of the antlers, he rode back and retrieved them, later giving them to saloon owner John Rozich to settle a bar bill. One night in 1922, riding back from a party at a ranch, Plute was pitched from the saddle. He died two days later. Ed Rozman, Rozich’s stepson, ended up with the saloon. In 1955 he had the antlers measured. A B&C score of over 442 inches confirmed them as the world’s record in 1961.

I’ve been blessed to use the .25-35, .30-30, .32 Special, .257 Roberts, .250-3000, 6.5×55, .308, and .30-06 on many successful hunts. None has brought me “book bone.” Maybe I should try the .30-40 Krag.