Hunters once had only to pick a ball to fit the bore. Then a French soldier had an idea…

by Wayne van Zwoll

When lead replaced stone and scrap-iron projectiles, soldiers and hunters must have celebrated with flagons of well-aged grog.

One huge advantage of lead is its specific gravity (SG) — its density relative to that of a standard. The common standard is water. A cubic centimeter, or 1 milliliter, of water at 4 degrees C (39 degrees F) weighs 1 gram. Specific gravity: 1. The specific gravity of granite, basalt, and similar rock ranges from 2.70 to 3. That’s why rocks sink. The specific gravity of lead is a whopping 11.3! Few natural elements top that figure. Uranium, gold, and platinum come to mind. Of those, only gold, with an SG of 19.3, is soft enough to cast or hammer into bore-diameter balls. Surely the prospect of defending kingdoms and killing deer with gold bullets silenced musketeers who whined about the cost of lead.

With its low melting point, lead is easily cast to slip into the maws of smoothbore flintlocks. But rifling, which appeared in the 16th century, made loading more difficult. While spinning the ball improved accuracy and extended its effective reach, a ball cast to groove diameter was engraved by the lands from muzzle to breech as the shooter pushed it home with the ramrod. From awkward positions on the castle’s parapet or mountain’s snowy slope, and especially with a bore already fouled by lead and powder residue, trying to seat a naked ball could take the soldier or hunter out of the action for pivotal minutes.

Then some gifted soul greased a patch. A land-diameter ball on a linen scrap that folded forward over it slid eagerly down the barrel. Saturating the cloth with fat or saliva not only accelerated seating but cleaned the rifling before each shot. The lube also filled land-groove corners to resist blow-by of powder gas. Upon firing, the patch “took” the rifling, spinning the ball then falling away as it left the muzzle.

Mass in motion generates momentum, and under the press of gravity, mass equals weight. Heavy balls carry the most momentum (the impetus of a projectile, or the product of its mass and velocity). But the only way to make a ball of any given material heavier is to increase its size. In flight, a bigger ball sets up more air resistance and drag than a smaller one. Any ball is an aerodynamic flop, with a low sectional density or SD — the ratio of its mass to its diameter squared. A .490 (50-caliber) lead ball scales 177 grains and has an SD of .105. A .535 (54-caliber) ball weighs 230 grains. Its SD is .115.

Conical bullets appeared when someone decided that, as they were heavier than balls of the same diameter, they had higher SDs. So, for any given mass and speed, they met less air resistance and retained their speed and energy better. At all ranges they carried more momentum.

Alas, the shape of a conical bullet makes it harder to load from the muzzle. While a ball, patched or not, has very little bearing surface, the bullet’s shank has a great deal of bore contact. Friction set up by that shank in the rifling can make front-loading a groove-diameter bullet darned near impossible in fouled bores. And a cloth patch won’t collapse forward or compress readily over a shank.

Modern bullets owe much to French army captain Claude-Etienne Minie — appropriately, if you think about it, as “bullet” derives from the early French “boulle” or “boullet,” for “small ball.” In 1847, Minie borrowed from a design by Henri Delvigne to develop a conical bullet with a hollow base. Firing drove an iron base cap into the cavity, forcing the bullet’s heel out to engage the rifling. War in Crimea, 1853 to 1856, tested this bullet. Meanwhile, James Burton at the U.S. Harper’s Ferry Armory eliminated Minie’s base cap. His version of the bullet, fired in Springfield muzzle-loaders, would cause 90-percent of the casualties suffered in our Civil War.

Inventive shooters eased loading with longer, heavier bullets than the Minie by way of paper patching. Bullets sized to the bore were brought to groove diameter by a paper wrap the length of the shank. Its “tail” was twisted or folded to keep it in place. As with linen, lubricating or moistening the wrap helped the paper adhere and improved cleaning action during seating.

Such bullets saw action in a famous 1874 rifle match fired at 800, 900, and 1,000 yards on New York’s just-opened Creedmoor venue. An untrained U.S. team was pitted against the Irish champs. Rifle authority Ned Roberts wrote that, “the Sharps Rifle Company brought out the Model 1874 Creedmoor long-range rifle with a 34-inch barrel chambered for a .44 calibre Berdan-primed, bottle-neck cartridge loaded with 75 grains of FG black powder and a 500-grain paper-patched bullet.” Remington followed with a match rifle on its Rolling Block action. The Irish, firing muzzle-loading Rigbys, were narrowly beaten. (A later, informal contest, in which the Americans weren’t allowed to clean their breech-loaders between shots, went to the Irish.)

Paper-patched bullets endured into the cartridge era. Shooters obsessed with accuracy in the late 1800s tested themselves and breech-loading single-shot rifles at 200 yards from a rest or offhand in the German “Scheutzen” game. Many barrels made by the famed Harry Pope were fitted with false muzzles that allowed the bullet to be inserted from the front, while the charged case was loaded at the breech. This method ensured against tiny nicks on the bullet’s base, which might affect accuracy. Typically, shooters reloaded a single case for a series of shots. For each, it was de-capped, re-primed, and filled to the mouth with black powder, then tapped lightly to settle the charge. A blotting paper wad secured the powder. The cast bullet, commonly paper-patched and lubed, was seated about 1/16-inch ahead of the case mouth.

On May 16, 1901, Colorado’s C.W. Rowland used a Pope-barreled Ballard .32-40 with Hazard’s FG black powder to fire a 10-shot .725-inch, one-hole group at 200 yards. It was incredible accuracy for the day and would be hard to equal with many modern rifles and loads!

Even now, period rifles with paper-patched bullets shoot surprisingly tight groups at velocities to 2,000 fps.

Breech-loading single-shot rifles, then repeaters, hastened the development of “naked” conical bullets in fast-twist rifling. In England as early as the 1850s, Joseph Whitworth had fired long small-bore hexagonal bullets through rifling that gave them a full rotation every 20 inches — steep pitch for that day. While those bullets yielded fine accuracy, they had to be indexed to the bore. With harder conical bullets in shallow fast-twist rifling, W.E. Metford also got excellent accuracy.

Harder lead alloy appeared as smokeless powder sent bullets faster. Soft lead that snugged Minie bullets into rifling wasn’t required in breech-loaders using groove-diameter bullets in metallic cartridges. And paper patching had no future in repeating mechanisms.

In 1882, Lt. Col. Eduard Rubin, who directed the Swiss Army’s lab at Thun, developed a copper-jacketed bullet. By 1886, it had been refined to load in the 8mm Lebel, the first cartridge of record to use smokeless powder. Meanwhile, Metford’s bullets were improved and adopted by the British Army in the 1888 Lee-Metford .303 rifle. The Lee-Enfield followed.

During the 1890s, smokeless loads that could send bullets over 1,900 fps triggered a stampede to metal bullet jackets. Tin plating reduced fouling; but the U.S. Army found tin could “cold-solder” to case mouths, hiking pressure. A bullet retrieved at a target range still wore the case neck! But in cupro-nickel jackets, tin didn’t cling to brass. In 1922, Western Cartridge had a Lubaloy jacket of 90-percent copper, 8-percent zinc, 2-percent tin. This “gilding metal” sired the 95/5 copper/zinc jackets popular today.

As velocities climbed during the next decades, so did stresses on bullets at impact. Jacket design changed apace. The front core in a Peters Protected Point bullet wore a gilding metal band and a pointed metal cone. Impact drove the band under the jacket to start and control upset. A Peters Protected Point bullet required more than 50 operations to make. Winchester’s Silvertip was much the same. In 1947, John Nosler used a mid-section dam of gilding metal (initially 90/10 alloy) to halt upset in tough going so the bullet’s heel would drive on. That year, in Sedalia, Missouri, Sierra Bullets began operations. In Nebraska two years later, Joyce Hornady founded another company, and his one-time partner Vernon Speer moved west to start yet another.

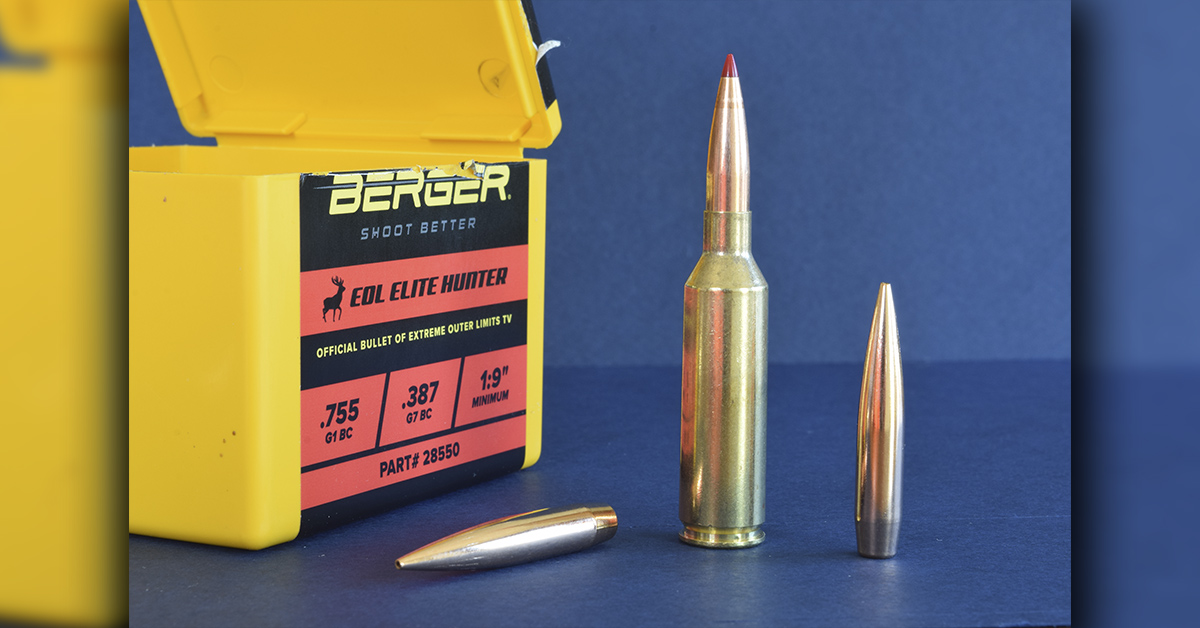

In 1985, Randy Brooks tested hollowpoint bullets made only of copper. Named for its four-petal nose, his Barnes X-Bullet is known for deep penetration and minimal weight loss. The Barnes TSX, or Triple-Shock, has upstaged it, with driving bands to enhance accuracy. Other brands have since entered the all-copper arena. Meanwhile, carefully guarded methods of bonding core to jacket have yielded bullets like Jack Carter’s Trophy Bonded (now made by Federal Cartridge). These commonly retain over 90-percent of their weight penetrating thick bone and muscle.

Tipped bullets have sold commercially since the 1930s, when Remington announced the Bronze Point. Its tip, harder than brass, had a concrete-piercing look. But impact drove the tip back into the core, which could rupture violently, limiting penetration. While the Bronze Point is history, polymer tips have proliferated. Soft and hard, depending on application, they’re sleek, colorful, and popular — though their contribution to ballistic coefficient (a measure of a bullet’s ability to cleave air) is often overstated. But that’s another story.