States throughout the U.S. have carved out special hunting seasons that up the game in terms of fun and challenge. If you are ready to try your hand at heritage hunting, here’s the scoop…

by Rob Reaser

As a kid, I longed to live in two worlds. I distinctly remember telling my dad that I didn’t know if I wanted to be an astronaut or a mountain man. I was hooked on Star Trek reruns by age eight. About the same time, the Robert Redford masterpiece Jeremiah Johnson convinced me that the rustic wilderness life might also be for me. Next thing I knew, I was busy making sapling bows and hafting flint arrowheads to slender, crooked sticks in my desire to live the ancestral life.

While I still enjoy sci-fi, I continue a lifelong fascination with the “old ways.” This includes archery and firearms. I have made several long bows and even a laminated recurve bow in my day, and I absolutely love shooting ball-and-patch muzzleloaders, be they of the percussion cap or the flint sidelock persuasion. There is something about the pungent smell of black powder smoke, the slow, methodical loading and shooting process, and the satisfaction of a shot well-placed with open sights that simply cannot be matched by today’s precision firearms, technical loads, and advanced optics.

It is this “return to roots” experience that holds much appeal to tens of thousands of hunters across the country.

As a native West Virginian and an early American history buff, going afield with my sidelock muzzleloaders represents a tangible link to the rough pioneers who first journeyed across the Appalachians, hunting buffalo, elk, deer, and bear along the tributaries and river bottoms, the high ridges and the dark hollows of these parts. In their hands were American long rifles, hand-made by the Pennsylvania school of master craftsman who immigrated from Europe and perfected the design to meet the unique needs of this emerging nation of settlers and explorers.

For me, there is an even more personal connection to this heritage. Our family camp sits on a humble parcel of land purchased by my great, great grandfather and grandmother in 1878. It is located above a small tributary that was once a centuries-old game trail that the Shawnee, coming down the Hocking and Muskingum rivers in Ohio, used to access hunting and raiding lands to points east. Before the Shawnee, peoples of the ancient Hopewell and Adena cultures had a settlement here. Those same great, great grandparents are buried on the ancient culture site located less than a mile from our camp.

The capstone to all of this, though, is the worn and beat up .32-caliber sidelock resting in my gun case. It was my great, great grandfather’s — no doubt used to punch rabbits, squirrels, and groundhogs for the stew pot from the same ground I now hunt deer using a .50-caliber Kentucky rifle I built from a Traditions Firearms kit some years back. It is deeply satisfying for me, when I’m walking the ridgetops and steep hillsides of our 7th generation property, to think that my ancestors were doing the same thing on the same land with the same type of gun nearly 150 years earlier.

That same spirit of wanting to connect with the past drives many hunters today to take up the primitive arms of our predecessors in pursuit of game (although their shooting skills proved there was really nothing “primitive” about these weapons). Recognizing this deep-seated need to honor our past with “living history” pursuits, such as hunting with the tools of our forebears, many states around the country have set aside limited seasons, usually after all the typical rifle and antlerless seasons have closed, reserved exclusively for primitive, or heritage, weapons like sidelock muzzleloaders and traditional bows (longbows and recurves).

Generally, these heritage seasons restrict allowable firearms to muzzleloaders with sidelock percussion cap or flint ignition systems. They also typically exclude the use of magnified or electronic optics. Permitted bows are longbows (English D-section or American-style flat bows) and recurves — compounds and crossbows need not apply.

Is it a challenge? You bet! The limitations of these weapons mean that the shooter must not only acquire the competencies and marksmanship abilities to use them (a long-term skill development in the case of instinctively shooting a traditional bow), but also deal with the range limitations of these weapons. Their short-range nature (yes, a well-developed load in the hands of a skilled shooter can stretch out the effective range of an old-school muzzleloader quite a bit, but for the typical patch-and-ball shooter, the envelope is around 50 to 75 yards) means the hunter must learn to…hunt. In other words, hone the skill sets of concealment, stalking, patience, and understanding game behavior to get within ethical killing distance. If you are only used to dropping deer at 100 yards or more from the security of an elevated box blind, for example, you’ve got some learning to do.

In addition to the satisfaction that comes from learning to take big game at close range with a weapon that is considered “primitive” by today’s sensibilities, heritage hunting seasons offer hunters a chance to ply the woods and fields when everything has calmed down. Deer have largely settled into their secluded winter routine. Bucks, especially, are worn out and drained from a couple months of sparring, fighting, and chasing does with little to eat and even less rest. They are hunkered down in areas where they feel secure and are trying to recuperate. The does, similarly, are holding tight between their bedding and reliable feeding areas, with little desire for traipsing across the countryside, looking, instead, to reserve fat stores and make it through the winter as the next generation grows silently in the womb.

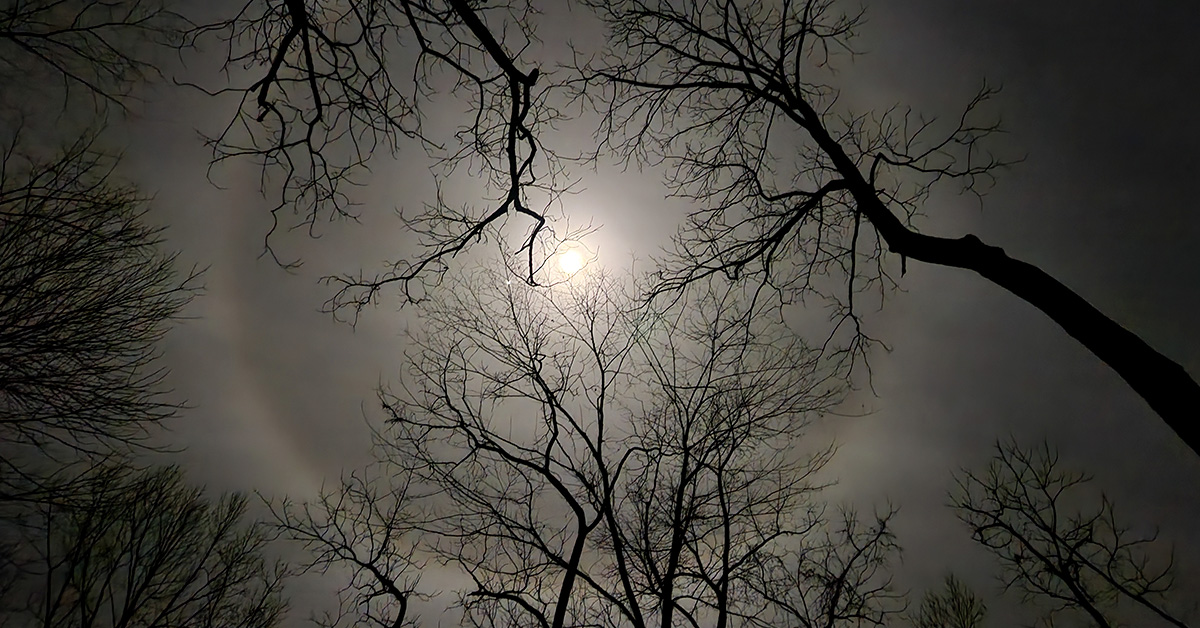

While all this can make for some challenging hunting, there are benefits in the experience. The woods tend to be exceptionally quiet this time of year. In my part of the country, there are no dry leaves rustling in the breeze and most of the more vocal birds have long since headed for warmer southern climes. The stillness is almost tomb-like, and it opens the mind to contemplation and a greater appreciation of what many see as a most dismal season.

In short, heritage hunting seasons are worth it on so many levels — far beyond the opportunity to put another deer in the freezer (although that is incentive enough in my book).

How do you start? Begin by studying your state’s hunting regulations to determine what equipment is permissible. Percussion cap or flintlock? Iron sights or fiber-optic? Minimum caliber is a big consideration (I recommend a .50- or .54-caliber for deer, although many a whitetail has fallen to a .45-caliber ball). Some states push the definition of primitive by allowing anything short of an inline ignition system. So, check your state’s rules and regulations first.

Once you know the parameters, you can choose your firearm and acquire the essential tools and materials to support the gun. Be forewarned! There is a lot to learn if you plan to go the old-school sidelock route. You’ll need to understand the differences in available propellants, projectile types, percussion caps and flints, which should be used for your type of firearm and intended use, how to develop a safe and accurate load, and more. I can recommend no better source of information for the beginner muzzleloader enthusiast than The Complete Black Powder Handbook by Sam Fadala. I believe it is long out of print, but it can still be found on Amazon as of this writing.

For those who want to shorten the learning curve and still be in compliance with most state regulations, Traditions Firearms recently came out with a solution called the ShedHorn, which we reviewed a couple months ago.

The ShedHorn has all the function of a classical sidelock muzzleloader but with one very important and appreciated difference — there is a removeable breech plug in the back of the barrel that allows the gun to be easily cleaned and the load (powder and projectile) to be removed without firing. Those who have long experience with cleaning and maintaining traditional sidelock muzzleloaders instantly recognize this feature as a huge win!

Another advantage of the ShedHorn is that it comes with fiber-optic front and rear sights. Compare this to the traditional iron sights. Not only is visibility enhanced, but the rear sight is adjustable for windage and elevation. The rear sight of many classic muzzleloaders is adjustable for windage only…and that is if you take a hammer and brass drift to it.

One of the downsides, for me, of the original-style muzzleloaders is seeing the sights in low light. During heritage season in West Virginia, everything often seems gray — from the wet leaves underfoot to tree bark and brush to the deer and even the sky. That makes it quite hard to get good sight alignment when the hour grows late. A fiber-optic sight, in these conditions, is a major assist.

Modern muzzleloader hunting is for everyone thanks to the latest inline ignition designs, improved projectile performance, advanced powders, and the ability to incorporate magnified optics, to name a few. Heritage muzzleloader seasons, though, roll back many of those advantages, but therein lies the appeal. A slower pace, a more methodical approach, and an elevation of the hunter’s shooting and woodcraft skills bring their own rewards. And for that, I can’t recommend it enough.