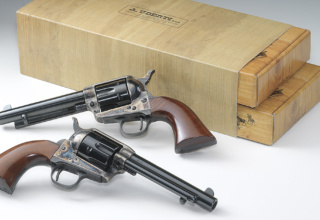

Uberti’s new Cattleman revolver combines elements of the Bronze Age with the latest 9mm loads!

by Wayne van Zwoll

James Butler Hickok, famously deadly with his 1851 Colts, might or might not have defended his reputation by drilling a miscreant through the heart at 100 yards. But the first four of five bullets from my single-action had just cut a ragged linear tear an inch across from 25 yards.

OK. The fifth had dropped 2 inches. And no one was shooting back. And yes, I’d taken my sweet time over the bags.

On the other hand, Wild Bill had young eyes, evidently still sharp that August day in 1876 when a .45 bullet from Jack McCall’s revolver crashed through the back of his skull at a Deadwood card table. It has been decades since my last sharp sight picture over a grooved top-strap.

“Little people, little pleasures,” said Alice when I showed her my target. So supportive.

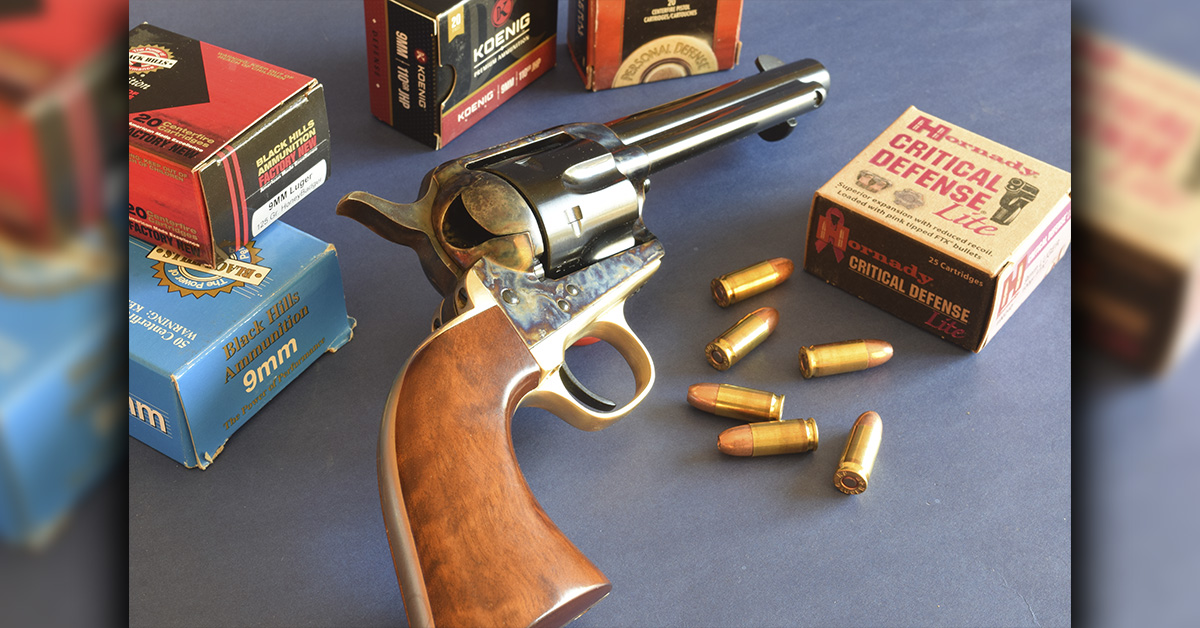

But I’ve yet to shoot better with a single-action than with Uberti’s new 1873 Colt reproduction in 9mm Luger. A Cattleman had come to my hand before, but in .45 Colt. The 9mm has a brass grip-frame and guard, a case-colored frame and hammer, deeply blued barrel and screws. The smooth walnut stocks are nicely finished. Components fit snugly.

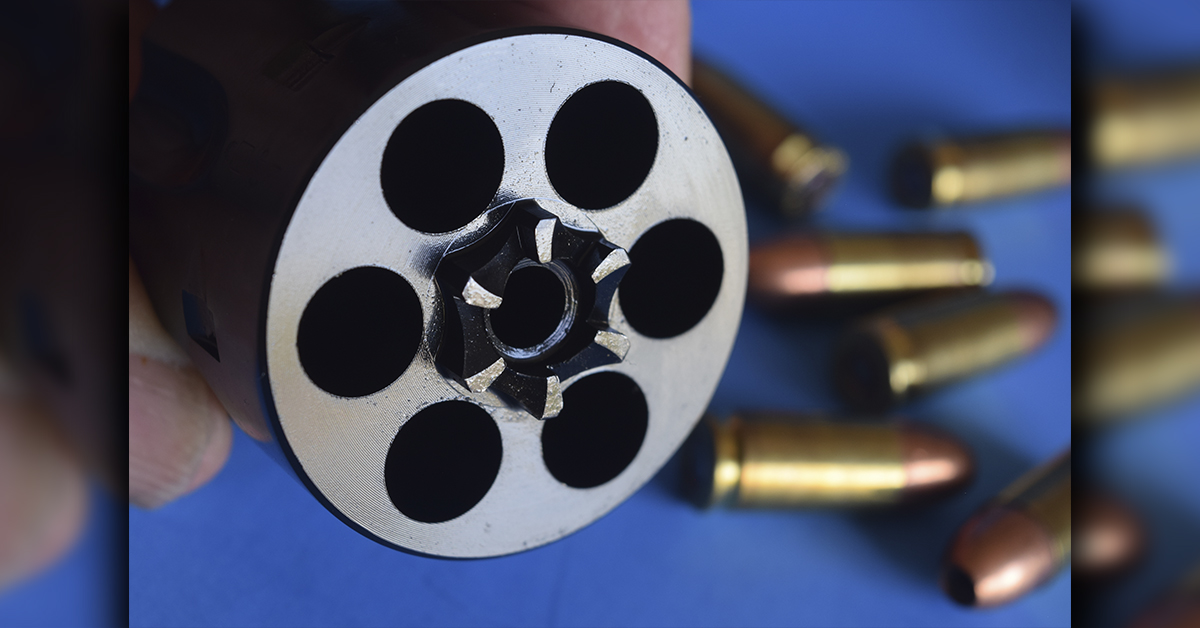

The cylinder for the rimless 9mm is not furnished with half-moon or full-moon clips, or designed for them. Its six chambers are bored so each cartridge headspaces on its mouth. Unlike DA revolvers with swing-out cylinders, the 1873 Colt SAA was fashioned for one-at-a-time loading and ejection. Thus, a metal clip holding multiple rounds has no purpose.

After un-boxing this Uberti, I brought the hammer to the first notch (of three) to free the cylinder and thumbed open the loading gate. Parts moved as silkily, and clicked to stops as crisply, as those of any Colt I’ve used. Black Hills subsonic 147-grain loads served for the first feeding. They slid home eagerly. The “half-cock” hammer notch locks the cylinder, also the trigger. The hammer spur is finely checkered, preventing slippage but not cutting thumbs. It feels like stippling.

Taping a paper target on a big box, I placed it at 25 yards, between tree rows in my small orchard, against cord-wood arranged to catch bullets. Settling the revolver over a Caldwell bag, covered to prevent burn from cylinder-gap blast, I squinted over the top-strap and thumbed the hammer to full cock… The group formed two inches to five o’clock. Hooray! The bullet holes were pleasingly close.

Another cylinder with the same load delivered that lovely 1-inch tear. I felt the muzzle dip on the last shot. Always the last…

Uberti also offers a “dual cylinder” rendition of its 9mm Cattleman, the second cylinder in .357 Magnum. The barrel’s groove diameter, I’m told, is .355. There’s now a 9mm El Patrón as well, with a blued steel grip-frame and guard and checkered walnut stocks.

Why a 9mm SA that looks and feels as if Colt built it before listing the SAA in .44-40? Well, it’s a gentle alternative to revolvers in .44- and .45-caliber, and firecrackers like the .357 Magnum. Even full-power 9mm loads are civil in this 38-ounce revolver. (Predictably, fast-stepping 115-grain bullets strike lower on the target than do 147s that log more bore time as the barrel lifts in recoil.)

Another reason for a 9mm is economy. At $599, this Uberti lists for a fraction of the cost of an original Colt; and it fires some of the most affordable centerfire loads. The 9mm Luger (9×19, 9mm Parabellum, circa 1902) has fed service pistols since its adoption by Germany’s Navy in 1904 and its Army in 1908. It is produced in great quantities by every major ammo manufacturer, in myriad loads with bullets of 90 to 147 grains. Improved powders and hollowpoint bullets have made the 9mm increasingly more effective. Lead-free missiles like the Black Hills Honey Badger and Lehigh Defense XP plow deep, leaving lethal wound channels. Bulk lots of 9mm hardball bring per-unit cost well below that of “practice” ammo in .45 Colt, .44-40 or .357 Magnum…even .38 Special.

This is hardly Uberti’s first revolver, or my first Uberti. The company dates to 1959, but its roots run deep in Italian gun-making. Perhaps fittingly, it’s now in the Benelli family, part of Beretta Holdings. Founded in 1526, Beretta is the world’s oldest gunmaker.

According to Tom Leoni, product manager for Uberti USA, Aldo Uberti was born near Gardone Val Trompia, on the hem of Brescia, Italy’s famous gun-making center. The area had been mined for iron ore since the Roman Empire. At age 9, Aldo was working as a stock polisher, and by 14 he had enrolled in the Zanardelli gun-making school. He apprenticed long hours at Beretta.

In WW II, Aldo joined the Italian resistance movement, the Partigiani. Captured by the Nazis, he survived detention in a German concentration camp. After the war, he returned to his trade, eventually setting up his own shop, Aldo Uberti Srl., to manufacture parts for the industry. But shortly, he was asked by two U.S. businessmen if he could make functioning, affordable replicas of Civil War-era firearms. Originals had become scarce and very costly. Nascent but growing interest in re-enactments and in sport shooting and hunting with period firearms promised a market. Aldo, like many Europeans, was much enamored of America’s “Old West” and in the firearms, people, and ethic defining that frontier. He took on the project.

A replica 1851 Colt Navy emerged first, then other revolvers and the 1860 Henry rifle. Aldo had a keen eye for detail and insisted on faithfully reproducing not just profiles but feel and function. His ’73 Colt revolvers and Winchester lever rifles got the attention of movie director Sergio Leone of “spaghetti western” fame. Uberti’s replicas were soon on the silver screen. Its Colt Walker appeared in the 1969 film True Grit with John Wayne, and a decade later in the hands of Clint Eastwood as The Outlaw Josey Wales. All firearms in the 1990 Dances With Wolves, starring Kevin Costner, were Ubertis. Several saw action in Tombstone, a 1993 production with Val Kilmer and Kurt Russell. Those are just a few of many movies featuring Uberti vintage replicas!

Aldo Uberti passed in the spring of 1988. The next year, the Beretta family bought his company and invested heavily in it, adding CNC machines to speed manufacture and grow the product line. Able management since has hiked sales of Uberti-built firearms stateside. They’re now imported by Cimarron and Taylor’s, both marketing them under their brands. At this writing, Stoeger also brings Uberti products to the U.S., but does not re-brand them.

The brass in Uberti’s 9mm Cattleman brought to mind a nagging question: Why brass in so many post-Civil War rifles and revolvers? And is it really brass?

Comprising mainly copper (60 to 90 percent) and zinc, with lesser amounts of tin and sometimes lead, brass predates iron. So does bronze, a harder alloy of copper and tin. Though copper may have been smelted in the Fertile Crescent of the Middle East as early as 6000 BC, history itself begins in the Bronze Age, 3300 to 1200 BC. (The Stone Age before is considered pre-history.) Sumerians were among the first people to use bronze. So, too, Cyclades Islanders in the Aegean Sea southeast of Greece. Later, its strength, flexibility, and corrosion resistance earned bronze a place in firearms, from cannon barrels to butt-caps on flintlock pistols. Relatively easy to make into tools and components, bronze has been called the strongest of metals.

Some “brass” in firearms is really bronze. Because they share copper as their main element, and tin and zinc have appeared in both, a line between them can be hard to draw. Also, there are many types of both. At one time, the U.S. Ordnance Department made “red brass” of 88 percent copper, 8 tin, 4 zinc. “Yellow brass” has less copper. The vague term “gunmetal” stuck to such alloys on firearms. Museums have found “copper alloys” a useful dodge.

The Volcanic pistol improved by Smith and Wesson in the early 1850s had an iron frame. Then investors bought in; Smith and Wesson left. Volcanic Repeating Arms Co. became New Haven Arms Co. under Oliver Winchester. He replaced the iron frame with bronze, a strange move for a struggling young company by some measures, as bronze cost more. Either metal was strong enough for the black-powder rimfire cartridges of the day. But bronze was lighter and more flexible than iron. And the color had sales appeal. The Volcanic’s successor, the 1860 Henry rifle, was hugely popular. It begat the first Winchester-branded firearm, its Model 1866, also known as the “Yellow Boy.”

Brass or bronze? You could just say the grip frame and guard of Uberti’s 9mm Cattleman make it a mighty handsome single-action revolver!