“Suppressor” is the word of the year. Get started on the right path with the first of a multi-part series on suppressor fundamentals.

by Jeremy D. Clough

The last decade has seen a surge in suppressor popularity, and the BBB legislation that eliminated the $200 transfer tax — the equivalent of nearly $5,000 when the National Firearm Act was first implemented in 1934 — has the industry poised to simply explode.

When I bought my first one over 20 years ago, things like suppressors (and, believe it or not, ARs), were transgressive. It just wasn’t done, and if it was, you didn’t talk about it. The paperwork, which was, you know, paper, required real live film photographs, law enforcement approval to even submit to the ATF, and you waited for 6-9 months for an answer.

As of this writing, the ATF’s eFiling system has reduced the wait to days. Of the several eForm applications I’ve done this year, none took over three days. Gone also is the stigma, with mainstream industry stalwarts like Ruger, SIG, and the notoriously conservative Smith & Wesson proudly advertising suppressors. Suppressors, cans, silencers, call them what you will, still require submitting a Form 4 application to the ATF, which must be approved prior to taking possession of your suppressor (you must purchase it before applying). They also still require notifying the chief law enforcement officer in your area, although you’re no longer required to have their approval. You have the option of either registering a suppressor as an individual or as part of a trust — a neat little bit of legal work that makes it possible for others to be added to it so they can share the item with you.

Candidly, I’ve always been a bit leery of trusts because I think they tempt some people to play fast and loose with the rules, and it never pays to get cute with the ATF. Created lawfully and followed religiously, though, it’s a pretty useful tool. Silencer Shop, who has handled all my eForm submissions, has an excellent kiosk system that greatly streamlines the process, and they also offer a trust service.

What hasn’t changed much are the basics of how a suppressor works: it traps or slows gas. Guns make noise several different ways, such as action noise or the echoing “crack” of a bullet breaking the sound barrier. It’s the sudden escape of gas, though, that the suppressor reduces. Other sources of noise remain unaffected by simply screwing on a “can.” Supersonic bullets still crack, semi-auto actions still clatter, shell casings still hit the ground.

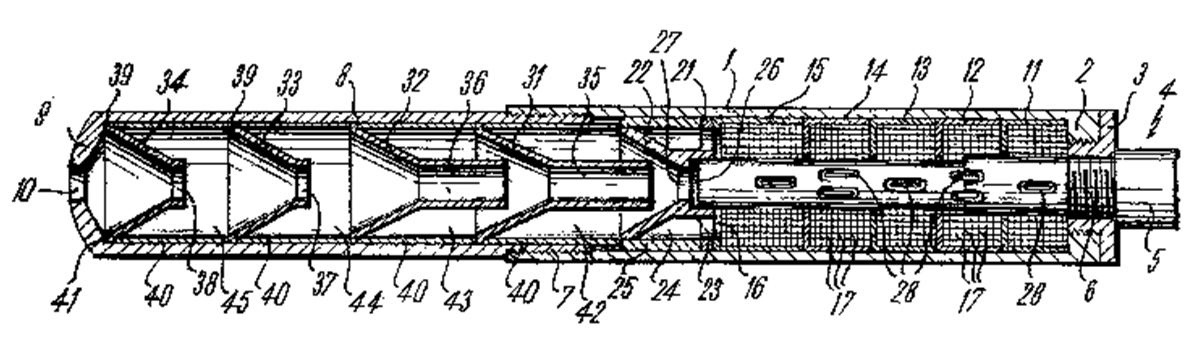

Most suppressors consist of a series of conical chambers inside a tube, often with a much larger blast chamber closest to the muzzle to take the initial shock of gas that exits in front of, with, and behind the bullet. Some have used packing material such as rolled screen or steel wool surrounding the bullet path, but the multiple chamber version is the most common. Think a bunch of funnels stacked backwards and you’ve got the idea. The concept was patented in the late 1800s. A washer or cone through which a bullet passes freely is called a baffle, and the lengthwise arrangement of them in the suppressor creates the baffle stack.

Herein lies another basic principle: the better a can traps gas, the quieter it is. The narrower the passage through which the bullet travels, the better the baffles shave off the sound-producing column of gas that comes with it. Unfortunately, the tighter the bore passage, the more unforgiving the suppressor is of minor errors in alignment often found on factory-threaded barrels. (AK, I’m looking at you.) And since baffles tend to be conical, there are tales of bullets exiting at 90 degrees out the side of poorly aligned suppressors. Given the choice between two suppressors with equal sound reduction, the one with the larger bore passage is preferable because it’s safer.

Some baffles, though, are designed to contact the bullet. Called wipes, they’re usually made of rubber or some other material that will “give” as the bullet passes through it and hopefully not direct it too far off course. Wipes are disposable items, and the suppressor will get louder as they wear. A classic Walther P38 suppressor actually used plastic discs with a scored “x” in the middle that the bullet punched though. One currently available suppressor comes with a wipe assembly packed with lithium grease that must be replaced as a unit at the factory after use.

That brings us to something else that affects suppressors: liquid can reduce sound.

Although less common now, artificial environment or “wet” cans are designed to be shot with water, oil, or grease inside. Obviously, anything that gets in the way of a bullet is extremely dangerous to the suppressor and everyone around, so just packing one full of grease is going to turn the end of your gun into a grenade. Before trying it, contact the maker to see if a given model is safe to be shot wet, and if so, how to do it.

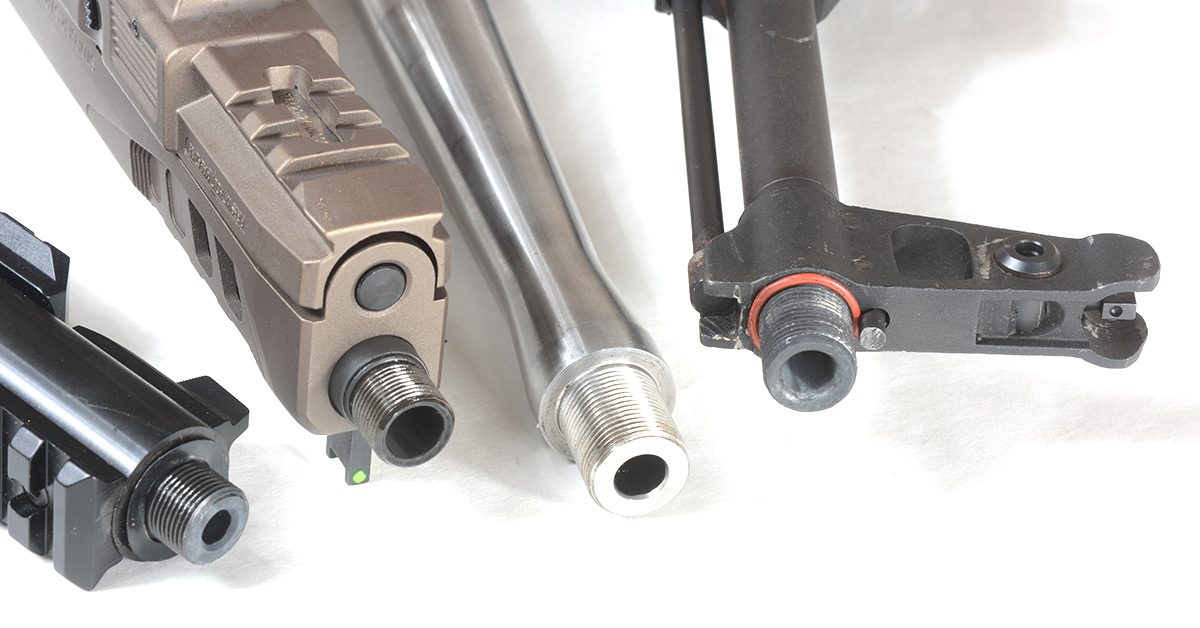

We’ll talk more about mounting systems in future installments, but the simplest way to install a suppressor is to thread it directly to the barrel. Some states have restrictions on firearms with threaded barrels, so make sure you know (and follow) your state’s laws.

You’ll have to make sure the threads on your barrel match the suppressor; there is some loose standardization between calibers and thread dimensions, but nothing is guaranteed. Metric threads start with an “M” followed by the diameter of the largest part of the threads (major diameter), in millimeters, then by the width of each individual thread, such as M14-1.

Imperial threads start with the major diameter in fractions of an inch followed by the number of threads per inch (TPI): 1/2×28, for example. Most are standard (as in, righty-tighty) while some suppressors and suppressor parts use left-hand threads, which can be useful to keep them from unscrewing. More on this when we get to rifles.

Assuming they’re legal, threads present two challenges, and the first is the precision of the muzzle threads. From the factory, they may or may not be concentric with the bore.

They may be off center or, worse, cut at an angle. Either risks baffle strikes inside the can. Even if you use some sort of quick-detach mounting system, the adaptor will likely thread onto your gun, so muzzle threads still matter.

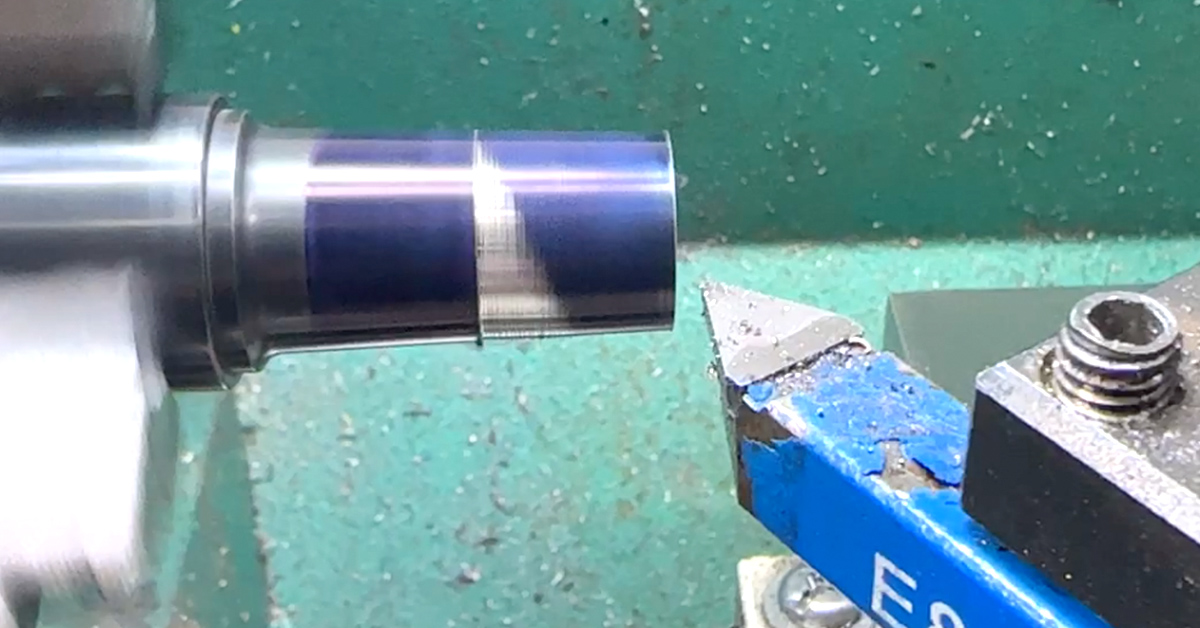

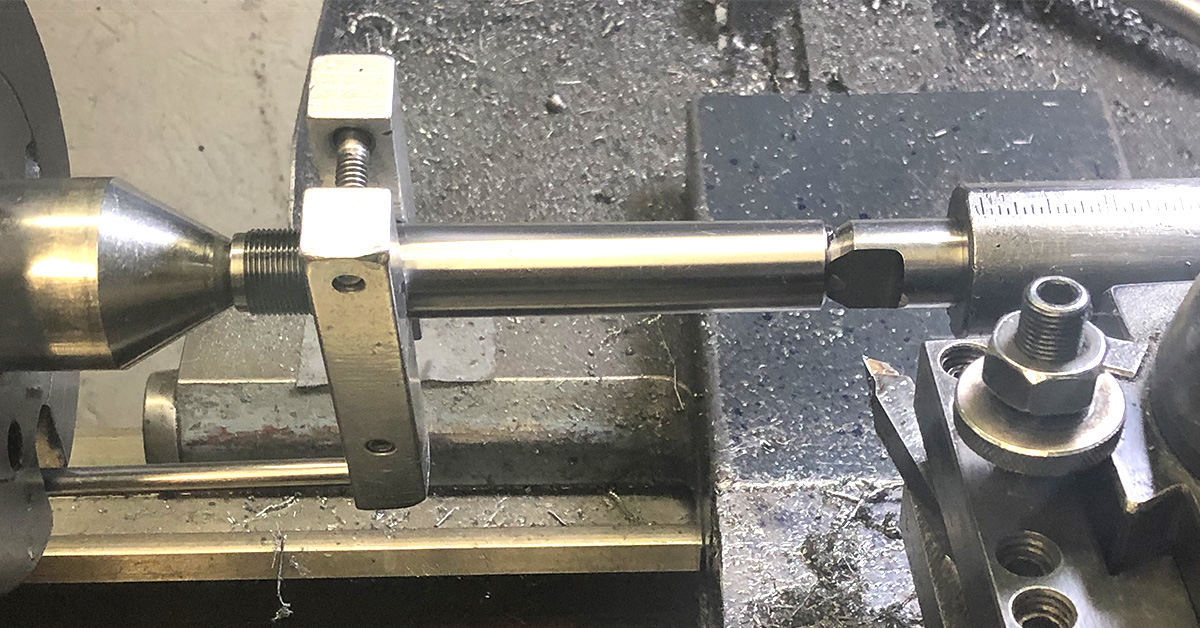

The gold standard is single-point threading in a lathe, with the barrel turned between centers. What this means is that each end is held in place by a cone that fits into the barrel. This centers everything around the bore passage, not the outside of the barrel, which may not be concentric with the bore. Most people won’t want to spend the thousands of dollars for the lathe, tooling, and education required to cut single-point threads themselves, so if your barrel isn’t already threaded, you’ll likely be replacing it or paying a machine shop.

That said, some barrels aren’t easily removed for threading in the lathe, and some people prefer to do it themselves. Dies are commonly available for threading barrels, but the muzzle already needs to be the correct diameter for the die to work. Furthermore, since the die is aligned by the outside of the barrel, not the bore, there’s a risk of misalignment. If you must use a die, use a pilot that fits into the bore to reduce that risk.

The second challenge with threads is that suppressors get very, very hot. Heat makes things expand, so cans sometimes start to unscrew during long strings of fire (some mounting systems incorporate a latch to keep this from happening). Keep an eye on it and always take something like an oven mitt or welding glove to the range so you can check tightness and retighten without having to wait for it to cool down completely. Suppressor covers are helpful as well, but they can also quickly get too hot to touch.

I won’t stake out much ground on dB reduction figures, but until every manufacturer is using the same decibel meter, and that machine is capable of responding to the sound of the shot quickly enough to measure the entirety of the sound wave it produces, it’ll be tough to get a 1:1 comparison between different models. Tone, also, may differ in ways that are not captured by electronic testing. Just like a video doesn’t fully replicate the sound of an unsuppressed shot, it’s not likely to produce a 100% accurate reproduction of suppressed fire, either. But these tools are the best we have short of firsthand experience.

Once the suppressor has captured the gas, there’s still the high-pitched crack of the bullet breaking the sound barrier. It varies based on elevation and other factors, but it’s around 1,100 fps. You can address that with the gun, or with the ammo.

Integrally-suppressed firearms have the suppressor built into the design of the gun, usually with a housing that surrounds a vented barrel and contains a baffle stack forward of the barrel proper. Classic examples are the Welrod single-shot and the High Standard pistol used by the OSS, the WWII-era precursor to the CIA, and which stayed in service for some 60 years.

Some, like HK’s MP5 SD submachinegun and a prototype 10/22 I shot that was in development for a hostage rescue team, have barrels intentionally shortened to reduce velocity, making it more likely that even supersonic ammo will be slowed below the sonic threshold.

Otherwise, you’ll be looking for subsonic ammo. Rifle ammo gets pretty specialized, but for pistol calibers like the 9mm, it’s often as easy as choosing a heavier bullet. Checking the velocity is an easy way to get quiet performance without paying the premium associated with rounds marketed specifically for suppressors.

This is especially true with .22 LR. The .22 bullet can destabilize when breaking the sound barrier, so match .22 ammo is often subsonic, as is standard velocity ammo. And you can always just try a box. I was pleasantly surprised to find Federal Auto Match is subsonic in my Ruger MkIV.

These are the suppressor basics. Next, we’ll look at the specifics of suppressing rimfires, rifles, and pistols.

- HUSH 101: Suppressor Basics - January 9, 2026

- Modifying Century Arms’ WASR AK - October 29, 2025