Long after the U.S. cavalry carried Colts, tribes stuck to the bow. Could arrows trump bullets?

by Wayne van Zwoll

The Oregon Trail, from Independence, Missouri, to Oregon City, Oregon, was established by fur trappers before 1815. Later, more than 300,000 settlers braved the 2,170-mile Trail, whose forks snaked to California and Washington. Fueled by the lure of free land beyond the Rockies, this migration began in the 1830s, peaked around 1843 and died with completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869.

Deaths on the Oregon Trail exceeded 20,000. Desert and mountain, sun, snow, and river crossings claimed some. Dysentery, typhoid, and cholera took others. Those who finished the trek did so with few possessions. Chattel from predatory Missouri hawkers was jettisoned early. Heavy heirlooms came next. Clothing and wagon parts hemmed the wheel ruts farther on. Discarded items were dubbed leeverites, as in “leave ’er right there.”

Oddly enough, records show hostile Indians accounted for only 362 pioneer deaths!

Tolerant at first of prairie schooners bumping across their hunting grounds, plains Indians — the Sioux and others — tired of the changes wrought in their wake by settlers stopping shy of the Rockies, of prospectors who brought more, and of market hunters draining resources to feed the legions to follow.

**********

In 1865, workers at Remington’s factory in Ilion, New York, sat by heavily-mortgaged machinery silenced by war’s end. Turning to the hunting market, Remington rushed Joseph Rider’s improvements on the Geiger split-breech mechanism and announced the Rolling Block Rifle.

Simple in design, the Rolling Block chambered a wide range of cartridges and was quick to load. It was stout, too. A test charge of 750 grains of black powder and 40 balls filled 36 inches of a rifle’s 40-inch barrel. Upon firing, “nothing extraordinary occurred.”

Buffalo hunters used Rolling Blocks to rake in as much as $10,000 a year in hides. George Custer used it, too, reporting after an 1873 hunt: “With your rifle I killed far more game than [did other hunters] … at longer range.” Three years later at the Little Big Horn, Custer’s troops died using Springfields.

Warriors who pestered settlers and soldiers didn’t warm as quickly to the Rolling Block. Like the dropping-block 1874 Sharps, the standard Remington was long and heavy, ill-adapted to fast horseback maneuvers that made the Sioux so fearsome in battle. Besides, these rifles fired cartridges that were often hard to find. The only ammo available to a warrior grabbing a .50-90 Sharps might be on its dead owner. A bow and its arrows could be made and repaired with natural materials.

Repeating rifles gave tribes a better option in firearms. The lever-action Henry of 1860, spawned by the 1849 Hunt Volitional Repeater, got lots of attention, though it saw limited action in the Civil War, and a 216-grain .44 Rimfire bullet, hurled by 26 grains of powder to 1,025 fps, had less punch at the muzzle than a modern .30-30 bullet brings to 350 yards!

Its progeny, Winchester’s Model 1866, used a 28-grain charge to launch a 200-grain bullet. But the Model of 1873 had real muscle. Its .44-40 cartridge hurled a 200-grain bullet at 1,200 fps. In 1878, Colt listed its Single Action Army revolver in .44-40. Packing one load that worked in rifle and revolver nixed mix-ups. And if the rifle or pistol failed, the other gun could still fire.

The .44-40 was once said to have slain more men, good and bad, than any other cartridge. Given its long service in lawless places, that’s a credible claim. Plains Indians coveted Winchester 1873s. Oddly, period artwork seldom shows warriors wielding Colts. Why might they have preferred bows and arrows to pistols?

**********

For centuries after gunpowder was invented, archers steered history. At the Battle of Hastings in 1066, Normans lured their English foes with a false retreat, then sent a storm of arrows into the oncoming ranks to win the day. England’s longbow was not so dubbed for its length, but for the archer’s draw, with an anchor at ear or cheek. Short bows of that day were drawn to the chest. Armor afforded little protection from English arrows, as archers aimed for the joints and for the exposed head of any soldier shedding his helmet on a hot day. They targeted cavalry horses, not only to maim and kill them, but to make them spill their riders.

In those days, English conscripts were required to practice with bows. Poachers were pardoned if they served the king as archers — a strong incentive, as one penalty for poaching was a hanging by one’s own bowstring! In 1542, an Act declared that no man of 24 years age or more might shoot targets at “less than 11 score distance.” That’s 220 yards!

On August 26, 1346, near the village of Crecy-en-Ponthieu, the French had found English archers could send 10 shafts a minute that far with chilling accuracy. If knights and their horses in battle trappings took 90 seconds to cover the 300 yards to the English front, they’d have met a hail of 7,500 arrows from a wedge of 500 archers. Each of 5,000 bowmen at Crecy may have had 100 shafts at hand. By one estimate, the English loosed half a million shafts that day, crushing “the flower of the chivalry of France.”

The English preferred yew for bow staves. But local yew wasn’t as straight-grained as that from the Mediterranean. Fearing the English in battle, Spain forbade the cultivation and export of yew. Not to be denied, the Brits required yew staves to accompany every shipment of Mediterranean wine!

**********

Bow design in North America borrowed not just from that of the British Isles but from peoples migrating from Asia across the Bering-Chukchi Isthmus. (Much earlier, the Chinese had built compact bows for cavalry and charioteers, and Turkish recurves put power into short, flat limbs.) Ash, hickory, and other hardwoods powered bows of American Indians in the East, Osage orange in the Midwest, soft yew in the Pacific Northwest. Some tribes used sinew to add cast and to protect the bow’s back at full arch. Horn on its belly added resilience under compression.

On the plains, mounted tribes favored short bows with wide, flat limbs. Galloping alongside bison, a hunter needed a maneuverable bow, but not the accuracy of longer bows made for stalking game afoot in the East. Arrows to skewer bison from a few feet didn’t have to be finely finished, and they often broke after one shot. Fletching was long because these crude shafts needed strong steering at the release. Raised nocks aided a “pinch” grip.

A plains Indian probably pushed his bow as much as he pulled the string. This technique helped him shoot quickly and get lots of thrust from a short bow. The bow’s length limited its elasticity and, with the archer’s horseback perch, made for a short draw. But even a 20-inch draw from bows of much lighter “pull” than the 80- to 100-pound English longbow stacked enough thrust to power arrows through bison. Texas Ranger Samuel “Bigfoot” Walker, who helped Colt develop its huge Walker revolver, remarked, “I have seen a great many men in my time spitted with ‘dogwood switches.’ [Indians] can shoot their arrows faster than you can fire a revolver, and almost with the accuracy of a rifle at … fifty or sixty yards.”

But however lethal England’s longbow, however skilled plains Indians at killing bison from horseback, why would the Sioux, among other tribes, choose a bow over a pistol? How would the two compare now as regards speed and accuracy?

A test came to mind.

**********

I’m no expert with bow or revolver; but not all who hurled arrows and bullets in the 19th-century West were either. Time and effort invested in survival on that frontier precluded the practice possible for sponsored shooters today. Arrows and cartridges were not instantly available, or to be spent in drills.

Fifteen yards seemed a reasonable distance for a test target. That’s double the hip-shooting range for combat training with handguns now, but, I suspect, closer than most hostiles would have approached each other on the plains before loosing an arrow or sending a bullet.

I don’t own an authentic bow from that era — and if one were available, it would have lost its cast. Too, the historical value of period bows argues against their use. I substituted my PSE recurve bow. It has no sights and pulls 55 pounds at my draw length of 30 inches. For a revolver, I scrounged a Colt SAA in .38 Special, with Speer 140-grain JHP loads. Yes, a .45 with original black-powder loads would have best represented what was available in the 1870s. But I doubt it would have significantly changed results.

The 5 ½-inch “black” of a 25-yard pistol target served as my mark. I’d try to hit it with six shots fired quickly with one hand, emptying and recharging the Colt to ready it for a seventh. Same for the bow. While the SAA could be fired faster, the bow would be “empty” for a fraction of the time needed to clear and reload the Colt’s cylinder singly from a cartridge belt.

After a few practice sessions to determine a hurried-but-reasonable rate of fire, I settled on a shot every 2 ½ seconds — not quite as fast as a rapid-fire string in NRA pistol matches.

When my first shots included wild pokes to beat the clock, I slowed a bit.

**********

“Record” sessions showed the bow to be quite effective. One pair of targets was representative, five of six shafts landed in the black in a 4-inch group. Five of the six revolver bullets stayed inside 4 ½ inches. As predicted, shooting cadence for the bow was a bit slower than for the Colt, but readying a seventh arrow was much faster than filling the SAA’s cylinder — which brought its total firing and re-loading time to 62 seconds.

Anecdotal, these results suggest the bow trumps the revolver by a slim margin. The push-pull act of shooting a bow, both hands, arms and shoulders involved, steadies it. Re-charging a revolver on horseback would probably extend its “empty time” by several seconds. But use of the bow requires more space than for the Colt and — unless you can clasp a galloping pony with one knee while coming to full draw under its neck — exposes you more. Tight against a dead horse, a combatant loosing arrows is more vulnerable than one with a Colt. The six-gun is also easier to point quickly at assailants to the side and behind.

Summing up, in the frontier West of the 1870s, I’d have muffed ridiculously close shots trying to save my scalp — with bow or revolver! At any level, panic quickly overrides competence. Add a galloping horse and put your nemesis on one, and you can credit any lethal hits to Fate!

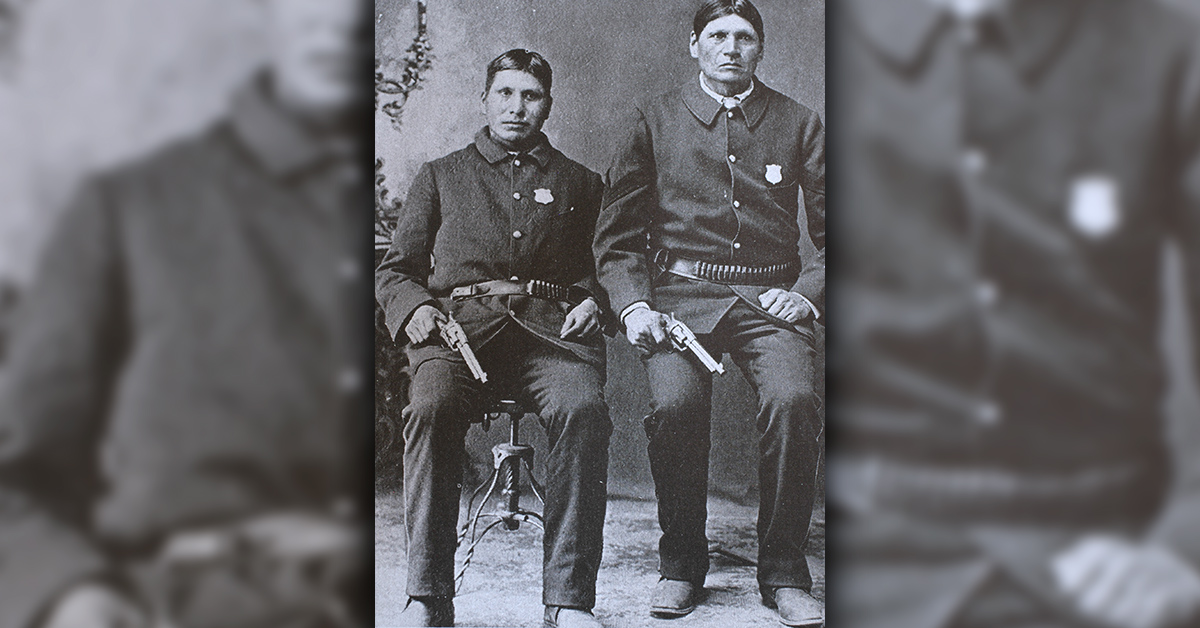

Late in the 19th century, Indian scouts were employed by the U.S. Army; some later served as law officers. Photographs show them armed with Colts.

Had automobiles arrived earlier, the best horsemen of the West would surely have re-considered their choice of the bow and arrow.

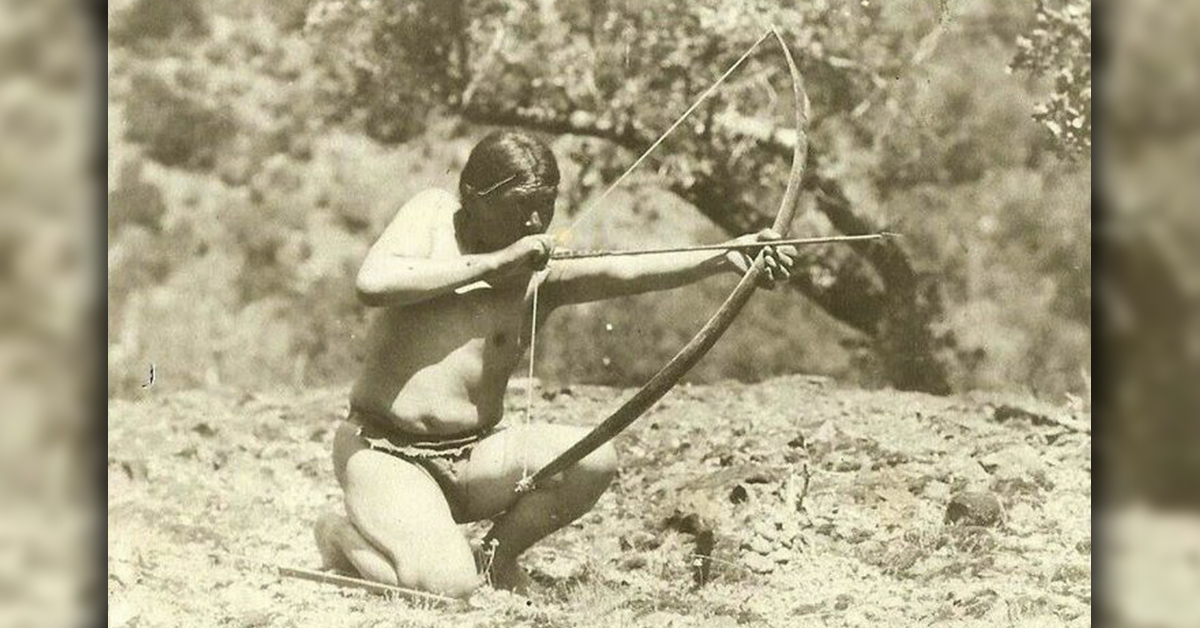

Ishi’s Bow

Plains Indians needed powerful but maneuverable bows to shoot bison from horseback. But even Ishi, the Yahi hunter discovered in California in 1911 and tended by Dr. Saxton Pope, favored a bow just 42 inches long. Whittled and scraped from a stave of mountain juniper, it had straight limbs 2 ½ inches wide near mid-point. Finished, it pulled about 45 pounds at Ishi’s draw length of 26 inches. It was easy to handle in the brush of Deer Creek. After Ishi’s death from tuberculosis in 1916, Dr. Pope and his friend Art Young hunted extensively with their own hand-built bows.

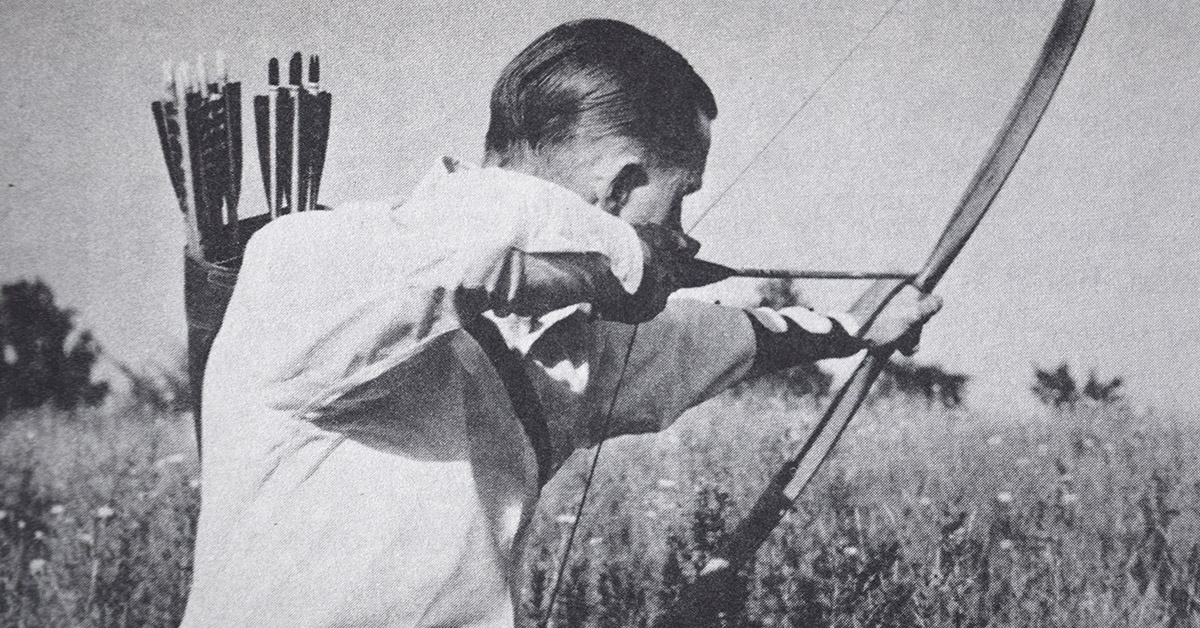

Horseback, and Canting…

English archers of the 14th and 15th centuries held their bows almost vertical to shoot. Tipping or canting a bow sends arrows in the direction of the cant. Still, a consistent cant can bring center hits! Plains Indians, like California’s Ishi, of the Yahi tribe, learned to shoot with the bow nearly horizontal, for use on horseback and in low cover when stalking game. Early photos of Fred Bear show his bow nearly vertical, but later images reveal a cant, even with short recurves. Howard Hill often canted to keep longbow limbs free. In exhibitions, he could hit small targets with the bow canted at extreme angles.