New optics are clearly superior, but dated rifles beg period scopes. Now you can have both.

by Wayne van Zwoll

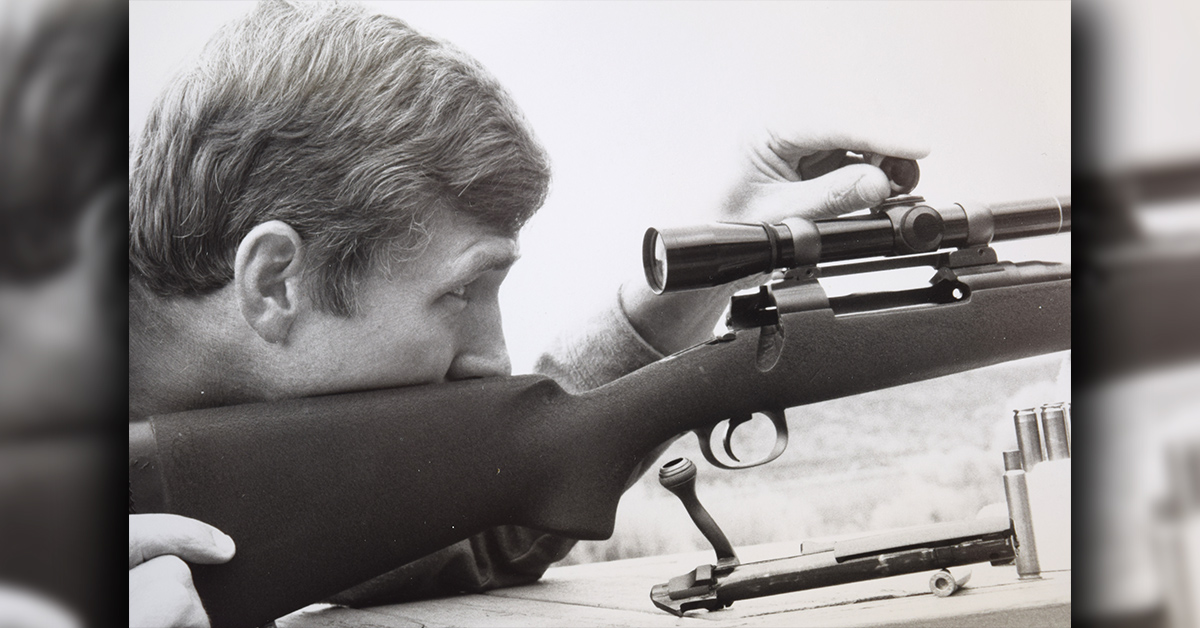

All the forest now lay in shadow. Turning back toward camp, I gaped at an elk with ivory-tipped tines right behind me. He stared as the .300 crept to my cheek. The Lyman’s field, it seemed, was all elk. But dusk had stolen the dot. Seconds ticked by as I tried frantically to find it. A pale patch of grass gave it up, faintly. I jerked it onto the elk and, as again it vanished, pressed the trigger.

I still like dots and Lyman Alaskans – albeit that scope, introduced in 1939, is generations behind modern optics in light transmission and resolution. Indeed, it was obsolete then. At a gun show soon after, I declined a new Alaskan in the crisp, original box. Price: $35.

Such foolishness, borne of youth and poverty, is now of the distant past. So too, sadly, Lyman’s Alaskan, discontinued in 1957. Leupold would revive it, briefly, with a fine reproduction.

You might call the 1930s, ’40s, and ’50s the golden age of optical sights. In 1930, at age 24, Bill Weaver designed then built by hand his 3x Model 330. He even developed the tooling to make it in his Newport, Kentucky, shop! This 10-ounce sight had a 3/4-inch steel tube, and internal windage and elevation (W/E) adjustments. The included “grasshopper” mount brought to mind a mouse trap with rings. About then, a Zeiss engineer in Germany found that coating lenses with magnesium fluoride reduced reflection and refraction, which could rob four percent of incident light at each uncoated surface.

In the 1940s, Oregon’s Marcus Leupold tapped his experience in the Merchant Marine to replace air in scopes with nitrogen, making them fog-proof. T.K. Lee invented his dot reticle, suspended by black widow spider web. Engineers designed erector pivots to keep reticles centered in the field of view during W/E adjustment. Meanwhile, 1-inch tubes replaced 7/8-inch; aluminum made them lighter.

Weaver and Leupold would earn big shares of a growing market in optical sights, Weaver initially with a spate of 3/4-inch scopes for rimfire rifles. These led to the J and B series in ’47 when the company also announced its 1-inch K2.5 and K4 scopes. The K6 arrived three years later, the K1 and K3 in 1958.

Leupold & Stevens had its first scope, the 7/8-inch 2.5x Plainsman, by 1947. An alloy tube held its weight under five ounces! In 1951, Leupold fielded three new scopes: a 2.25x Riflescope and 2.5x and 4x Pioneers. At $64, the Riflescope wasn’t cheap. For $27.50, a High Power Converter hiked its magnification (and that of a 2.5x Pioneer) to 8x. A 4x Riflescope joined the roster in 1953. Within a year, the company produced its first 1-inch scope, the 4x Mountaineer. An 8x Pioneer, an 8x Westerner, and a 6x Mountaineer followed. All Pioneer scopes were dropped by 1960, when Leupold announced its M-7 3x and 4x scopes. A year later the 3-9x Vari-X appeared.

Meanwhile, Lyman had built on the reputation of its Alaskan with the 4x Challenger. Arriving in 1949, it had a 26mm (1.023-inch) tube. So did 6x, 8x, and 10x Wolverines, introduced in 1954. That year, the All-American series — 2.5x, 3x, 4x, 6x, 8x and 10x — brought 1-inch tubes to Lyman’s roster. Perma-Center reticles followed in 1962.

While Lyman is still a vibrant member of the shooting industry, scopes dropped from its catalogs 40 years ago. Some post-Depression competitors wouldn’t survive in any form. By the mid-’30s Rudolph Noske’s shop in San Carlos, California, was producing four 7/8-inch Fieldscopes, two 2.5x models and two 4x. A Noske was the first internally adjustable U.S.-made hunting scope. It was also among the most expensive at the time. In 1939, when a Zeiss Zeilklein fetched $36, Rudolph priced his Fieldscopes above $50. The Noske shop closed after WW II.

Zeiss, of course, is still with us. But the 2.75x Zeilklein scope, developed by the Hensoldt Optical Co. in Wetzlar, Germany, is long gone. The Zeilklein and 4x Dialytan date to the 1920s. They had 22mm (7/8-inch) tubes and, at a $6 additional charge, internal adjustments. Hensoldt fans of the ’30s included famous hunters. Col. Townsend Whelen praised the Zeilklein in his 1936 book, Telescopic Rifle Sights. He used it on a Winchester 54 in .270 in British Columbia, bagging several deer and two moose — also a caribou at 360 yards. Jack O’Connor favored this rugged, optically fine 2.75x sight on his early hunts. Its price climbed just $11 during the 15 years preceding WW II. Absorbed by Zeiss in Wetzlar, Hensoldt sold scopes under its own name stateside as late as 1968.

By this time, Bausch & Lomb Optical Co. of Rochester, New York, had been two decades into the riflescope business. Founded in 1853 by John J. Bausch and Henry Lomb, it first made eyeglasses and scientific instruments. By century’s end, its binoculars and telescopes were profitable. B&L supplied these and rangefinders to military units in WW I. Beginning in the 1920s, B&L produced riflescope lenses for Lyman. That relationship gave way in 1945 as B&L began designing its own scopes. By 1950, it had the 2.5x Baltur, 4x Balfor, and 2.5-4x Balvar 4, all with 1-inch tubes. The Balsix, Baleight, and 2.5-8x Balvar 8 and 6-24x Balvar 24 followed. Lacking internal adjustments, all early B&L scopes required adjustable mounts. W/E dials would appear on the company’s Trophy models in ’68.

The foregoing are just a few of many scope-makers, domestic and foreign, whose optics served hunters during and after the Depression, on rifles we call “classic sporters.” Winchester’s 54 and early 70, Remington’s 721 and 722, commercial Mausers, and modified Springfields defined that clan. Marlin 336 and Savage 99 lever-actions benefitted from the same scopes. Most of the rifles built before WWII had to be drilled and tapped locally for mounts.

As scopes now deliver brighter, sharper images and more precise adjustments, with features not dreamed of before the 1960s, what does it profit knowing about old optics? If you’re a history buff like me, knowing is its own reward. Beyond that, you may wish to equip a rifle from that era with a scope of like vintage. After all, you don’t cinch alloy wheels onto a fine, otherwise-untouched ’57 Chevy.

But where will you find scopes decades discontinued? Many are stuck on old rifles in closets and gun safes, unavailable. Others, replaced by newer models, are damaged. Still others, well-used but sound, lack the brand name, condition, or inherent quality to draw second-hand sales.

“That’s why I started Vintage Gun Scopes,” says James Brion, 56. A Nebraska native, he lives in Montana’s Bitterroot Valley, where his Corvallis shop services and sells old scopes. “We’ve never sold a used scope,” he clarifies. “All are refurbished, re-glassed, or restored.” Refurbishing includes a thorough cleaning and re-lubing because old grease can harden. Where needed, fresh seals are installed. “We zero out parallax as close as the engineering of the optic allows.” To prevent fogging, each scope is “nitrogen processed” or “nitrogen purged.” Then it’s graded, optically and cosmetically, and readied for shipment in a wooden box with a sliding cover bearing the VGS logo.

Re-glassed VGS scopes get that treatment plus modern coated lenses (when available) to replace those optically compromised by age, wear, weather, and, in many cases, the lesser quality of original glass and coatings. Restored scopes add new-looking exteriors to re-glassed optics. To my eye, the finish of a sample VGS-restored Alaskan is indistinguishable from that of the lightly-used Alaskan on my early .270 Winchester Model 70. Ditto a comparison of old and restored Weaver K2.5s. Importantly, in my tests with an optometrist’s chart for vision checks, the lenses of VGS-restored scopes trounced the old originals in brightness and resolution.

VGS dates to 2017, but James has been using scopes since his youth, when his family introduced him to firearms and hunting. His interest in vintage scopes dates to 1984, when he was 16. The Weaver factory had just shuttered.

“We won’t see scopes like that again,” a gunsmith told him. “Buy up as many new Weaver scopes as you can.” He did, including more than 10,000 left over from Weaver’s auction. He still ranks the Weaver K6 60B among the best all-around hunting scopes, the K2.5 and K4 of that era its equals for traditional whitetail rifles.

“Unfortunately,” Brion adds, “60Bs didn’t come with plex reticles.” Installing the versatile plex in 60B scopes is one of very few modifications he allows in vintage scopes.

While Weavers account for most of his business in hunting optics (Redfields and Leupolds next), he considers Kollmorgens “decades ahead of their time.” Among target scopes, he says, “Unertls are an engineering feat and a work of art.”

On the VGS website you’ll find scopes that are now mighty scarce. Noskes, for example. In my youth, I bought then foolishly sold the only Noske I’d ever seen. Brion recently listed a 4x in very good condition. Incidentally, his shop is also a source of rings needed for the 7/8-inch and 26mm tubes of many vintage scopes.

James Brion still has roots in Nebraska, where he began outfitting hunters for deer and turkeys in 1991. He reports that hunters from his camps have shot about 3,500 turkeys. Besides building Gobble n Grunt, Prairie King Ranches, and other outdoors businesses, he has hunted around the world. He uses modern rifles and modern optics as well as vintage gear. But he doesn’t mix them.

“If I have a rifle from 1959, it will have ’59 mounts and scope.” An obvious match, now more accessible to any rifle enthusiast.